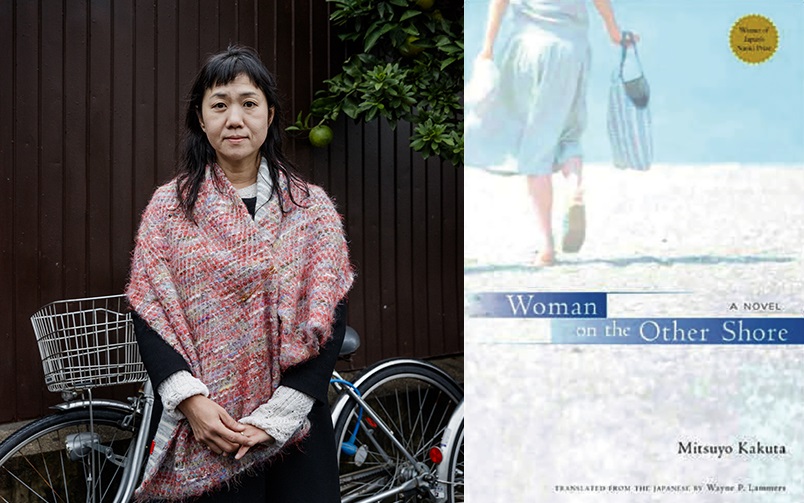

Kakuta has written a wide variety of novels and depicted the lives of many different types of women through her characters.

Kakuta has written a wide variety of novels and depicted the lives of many different types of women through her characters.

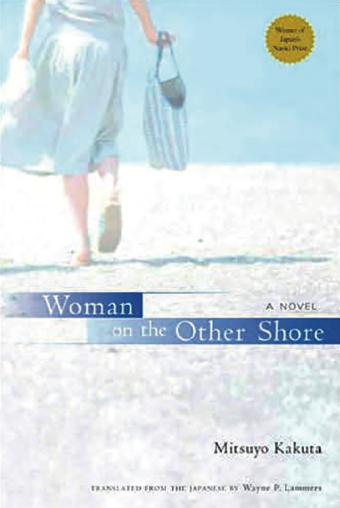

Having received a number of literary awards during her career, Kakuta Mitsuyo is now considered as one of the leading authors representing Japan today. Her 2004 work “Woman on the Other Shore” will be published in Spain soon, but preceding this she travelled to London on the invitation of the Japan Foundation to take part in a talk show. Zoom Japan asked this champion of female literature about the state the country and womanhood in Japan today.

Ms. Kakuta, I hear that you wanted to be an author since you were in primary school. Why at such a young age and why did this desire not change over all that time?

Kakuta Mitsuyo: I liked reading books since I was a girl, but I also found it very hard talking to people. When I went to primary school and had to write compositions it was because I read so much that I could already write fluently. I was so happy about that and in year one when we were asked to write about what we wanted to be in the future, I wrote that I would become an author. I decided on that path so early that from then on I did not study for other subjects such as maths or social issues. I thought that I would be fine only studying for Japanese language classes, and so in years four and five of primary school I no longer understood any of my lessons apart from Japanese. Even after I went up to middle school it was unsurprising that although I could do Japanese language, I had no foundation in any other subjects and so was unable to do any of them. Because of that I could see no other options but being a writer really.

What kind of books did you read? Did you have any particular favourite authors?

K. M.: I liked Matsutani Miyoko a lot and also earnestly read the fairy tales of Miyazawa Kenji. And I liked foreign authors too, although when you are little you don’t really think about where a story is from or differentiate by countries do you? So I read British novels like Mary Poppins or The Secret Garden without really knowing they were set in England, and when I grew up I just came to understand and accept it naturally.

The first novel of yours that was published was actually a junior novel, but how did that debut actually come about?

K. M.: I wanted to become an author as soon as possible so I submitted a piece to the newcomer award section of a literary magazine when I was 19. I stayed in the running right until the finalist candidates stage but ultimately failed to go any further than that, although each of the finalists was assigned someone from the magazine to handle them. My contact told me that the magazine had a department which brought out novels for young children and asked if I would be interested in writing for them as I was still only 19. I wanted to make my literary debut as quickly as possible, so I agreed to write something straight awy, without really understanding what the young girls novel genre was even about.

I think it must have been completely different from the kinds of pieces you had already submitted to literary magazines. What was it actually like?

K. M.: It was very different and what I had previously wrote just did not fit the genre (laughs). Young girls novels are quite a specialist genre, and in some ways the marketing side and sales performance play a bigger part than with other literary genres. In the end it was clearly very different to what I wanted to write myself and the two years I spent writing those novels were a very tough time for me.

So how many novels had you already written before you submitted it?

K. M.: The University I went to had a seminar on novel writing and in that seminar I had already written several pieces before I wrote the submission.

After that you went on to receive the Kaien literary newcomer award and you released your work primarily through literary magazines, but did something change inside you when you first started writing entertainment novels?

K. M.: Not really. It was simply a case of the work drying up in the field I was in at the time. In Japan you have quite strictly defined categories known as “pure literature” and “entertainment novels” and whichever one you debut in pretty much decides which literary world you will become a part of. This is a very standard thing in Japan but probably quite a strange phenomenon in almost any other country. I had debuted in a pure literature magazine, and that is why I wrote for those kinds of publications for around 10 years. However, my books just did not sell very well and even though I was nominated for literary prizes I would continuously fail to get through and win. My options got narrower and narrower and it was when I started to wonder what I was going to do about it that a representative of an entertainment novel magazine got in touch and asked if I would write for them too. So that was when I first realised that there were still other avenues out there for me to write.

K. M.: In actual fact my range of interests is very narrow, and if nobody requested that I do these special projects then I would probably not look at paintings or really do anything new at all. If I were only to write about the things that I want to write about then it would probably wind up a very narrow experience indeed. On the other hand, being asked to write a novel together with a piece of art or to do a collaboration with a certain photographer etc. makes me take an interest in things that I would not have been moved towards otherwise, so I am kind of happy to do things this way and it is a help for me.

A lot of your works cover the themes of parent and child relations and becoming a mother. Why these kinds of themes are so prevalent in your work?

K. M.: I have a feeling that 20 or 30 years ago, when I first started writing about those kinds of themes, there were not many people writing about such things in Japan. It is only really very recently in Japanese society that people can say openly that they have difficult feelings towards their parents or talk about not getting on with them, and the numbers of those kinds of voices are increasing. Also it was a theme that I was particularly interested in personally. I feel that perfect mother – daughter relationships where they always get on well together just don’t exist anywhere in reality. Whether they get on well or not, there is something undeniably special and different in the way mothers and daughters relate to each other, compared to the relationships between mothers and their sons.

It has been a long time since the declining birth rate issue was first raised in Japan, but what problems and shortcomings do you see with the country’s systems and thinking here?

K. M.: This might be at a tangent to the original question, but many young twenty-somethings these days say that they do not need boyfriends or girlfriends. In numerous surveys and other research it comes back that 60 to 70 percent of people do not have a significant other and among them are those who have not had sexual experiences. And many of them also say that they don’t need anyone at all. This may well be the first time this phenomenon has been seen and I think that the government is also worried by it. That is why they are doing all sorts of things to try and change the situation, such as “machi kon” (Large scale drinking parties across whole towns with the purpose of creating opportunities for young people to meet and mingle with each other and also to revitalise the local area). But I really cannot understand that psychology that they don’t feel they need a boyfriend or girlfriend myself.

Do you think that marriage and childbirth are things that greatly change a woman’s way of thinking?

K. M.: More importantly than that, I think that Japanese women have only really just reached a point where they can choose for themselves whether to get married and have children or not. So I feel that the very fact that women have come to understand that they can be happy in life regardless of whether they marry or have kids has a much bigger influence on their lives.

I heard some time ago that you firmly decided that your work only takes place between 9 to 5 Monday to Friday, with no overtime, but is that still the case today?

K. M.: From last year I decided that the morning could actually start at any hour. So I can start from 7, or from 10, but I still always finish at 5.

Is it not hard to keep control while you are so busy with work?

K. M.: My busiest time was around 10 years ago, and back then I was so busy that I actually don’t have many recollections of the time. So I decided that I would cut down on the amount of work I do and finally managed to bring it down to a manageable level.

Recently there was a sad story in the news where a young female employee who had just joined Japan’s largest advertising agency killed herself due to overwork. What do you think about the modern Japanese attitude towards work?

K. M.: I think that there is too much of a gap there. The case in that incident was quite unique. She was an elite employee and had entered a very good, large company, but was asked to work too much. Another thing that is becoming a problem for society is when university students apply for part time jobs and the companies turn out to be exploitative sweatshops that work them day and night regardless of their wishes. And on the other hand there are people who want to work but are unable to, as there are no jobs, so I feel that there is really too big a gap between different things here. It is a unique phenomenon for the age we live in.

A while ago an advert from the cosmetics company Shiseido was pulled from the air under heavy criticism for the sexual harassment in its slogan “After 25 you are no longer a girl”…

K. M.: Really? I had not heard that. Was it recent?

Yes, it was only about one month ago. In this commercial a girl who had just had her 25th birthday is told by a friend that “From now on you are no longer a girl. You won’t be made a fuss of any more. You can no longer use your cuteness to get ahead” and that she must now “aim for the beauty of a mature woman”. It then links in to a promotion for some cosmetics. There was quite a vigorous debate among prominent figures about this advert and various opinions were offered. Some were saying that there was no choice but to pull it as it was degrading towards women, while others pushed back with the argument that those who got upset about it were supporting a value system where women have no value unless they adhere to a standard of cuteness.

K. M.: I would like to have seen that.

You have been successful in your writing activities since your early twenties, but have you changed as a woman or in how you think about things in the time since then, through your 30s and into to now?

K. M.: I think I have changed a lot yes. I had very little life experience back in my twenties, so my thinking was rather shallow. As I have become older, those around me have gotten married, become parents and either become sick themselves or needed to look after their elderly parents. The burdens placed upon them have changed with where they are in their lives and I think that also changes your outlook. There are changes that take place within people as they get older regardless of the kind of job that they do, but to link it to the previous topic, I think that maybe ones age is not all that relevant for a novelist, at least from the perspective of how people treat you. I made my debut at 23 but nobody spoiled me or sugar coated things because I was so young, and now I have become older people still don’t give me more leeway on things because of that. In that sense it was quite easy for me as this job has not made me feel particularly aware of any changes in my womanliness from getting older.

K. M.: It is indeed quite strange that a lot of times my readers tell me that they really understood the emotions of my characters. I keep quite a distance from those characters and often feel things like “I really don’t like someone who would do the things that this character just did” while I am writing, so it does surprise me. But perhaps this phenomenon is because the way I write is so dense and cloying. I don’t leave any gaps and sometimes write way too much detail on the internal psychology of my characters, along the lines of “He said this to me so I felt this” and then “because I felt this I then went and did that”. I think that may be a flaw of mine, but if the readers feel understanding and empathy with even one aspect of that kind of overwrought discourse then they will probably continue to be dragged along by it.

You are also involved with translating picture books. Were you always interested in translation work?

K. M.: I was, yes. I was interested in converting other languages into Japanese from a long way back. And I like the English language as well. I don’t have that great a linguistic ability, but it probably comes from the fact that it was the first foreign language that I had contact with. If I try my best then I should somehow manage to understand don’t you think?

Is there anything you feel is difficult about translation when you are doing it?

K. M.: For picture books the text is very simple, so rather than trying to render what is being said as accurately as possible, it is more about having to listen to the voice of what is written and then create a new rhythm for it in Japanese and I think that is what is hard.

You also sit on a lot of judging panels for literary awards. Is there any reason that you took on that role?

K. M.: One reason is that there are an overwhelming number of people who don’t want to do it. But one other thing that I have come to realise since I started doing awards judging is that it is actually fascinating. Especially with newcomer awards where amateur writers submit their stuff, it really does let you see how the nature of literature and the novel itself change with the times from right there on the very cutting edge. For example, after the great disasters of 2011, nothing really changed immediately, but after 2 or 3 years the very nature of novels seemed to change. Being able to see and feel that evolution first hand is very stimulating indeed from the perspective of someone who is also a writer.

What specific kinds of changes were there after the disasters?

K. M.: What I saw most was more fantastic stuff being written, that moved away from reality slightly. This was not pure fantasy but was not the real world we all live in either. There was a huge increase in stories set in places like that, such as simulated realities where slightly different rules govern things. Ten or so years ago you would see lots of works that had a fairly strong smell of reality to them, set in heavily mundane settings, where the main character was a young casual worker without a career who part timed in a convenience store and had a sort of ill-defined relationship with someone who you could not really call a steady partner and so on. I thought that it was an interesting phenomenon how that kind of story disappeared almost completely after the disasters.

Why was there that move into fantasy worlds because of the disasters I wonder? Perhaps it is because people experienced that however diligently you build in the real world, it can all be swept away in just an instant?

K. M.: I think that does have something to do with it. Back when authors tried to write things that were exactly the same as the reality that they inhabited, they probably thought that state of affairs would continue forever. But in actual fact that was completely not the case and when they came to understand that it could disappear in an instant, that really changed people’s perceptions of the novel, especially young people. 5 years have passed since then and it is still slowly continuing to change. I am very happy that I can see that happening myself.

INTERVIEW BY SATOMI HARA

Leave a Reply