A cornerstone of Zen aesthetics, dry gardens hold many mysteries, but are a source of well-being.

“To comprehend the beauty of a Japanese garden, it is necessary to understand the beauty of stones.” So said Irish-Greek writer Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), whose books about Japan were instrumental in introducing Japanese culture to the West.

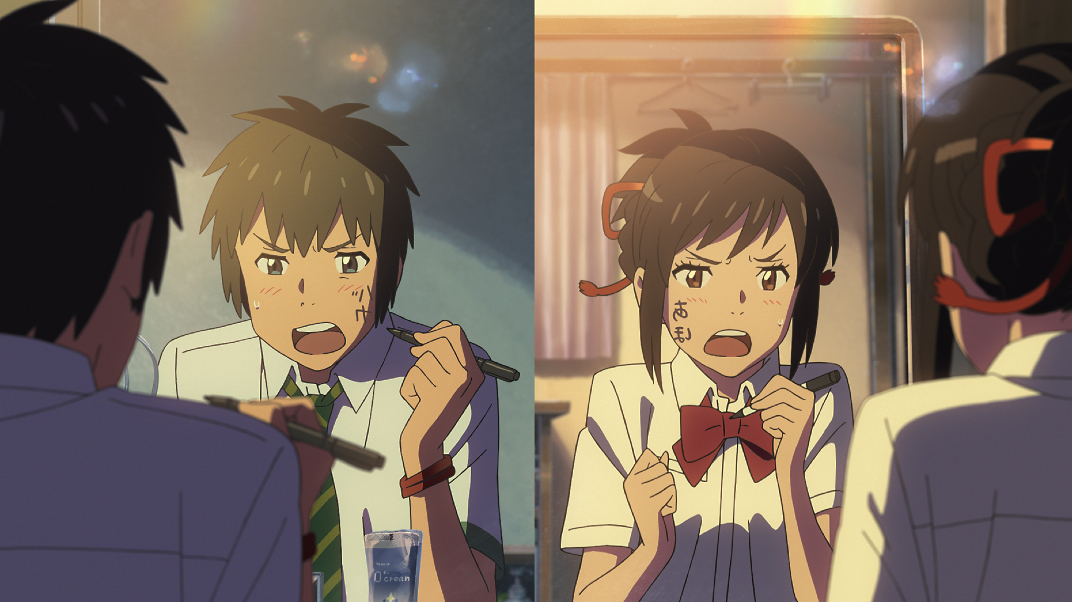

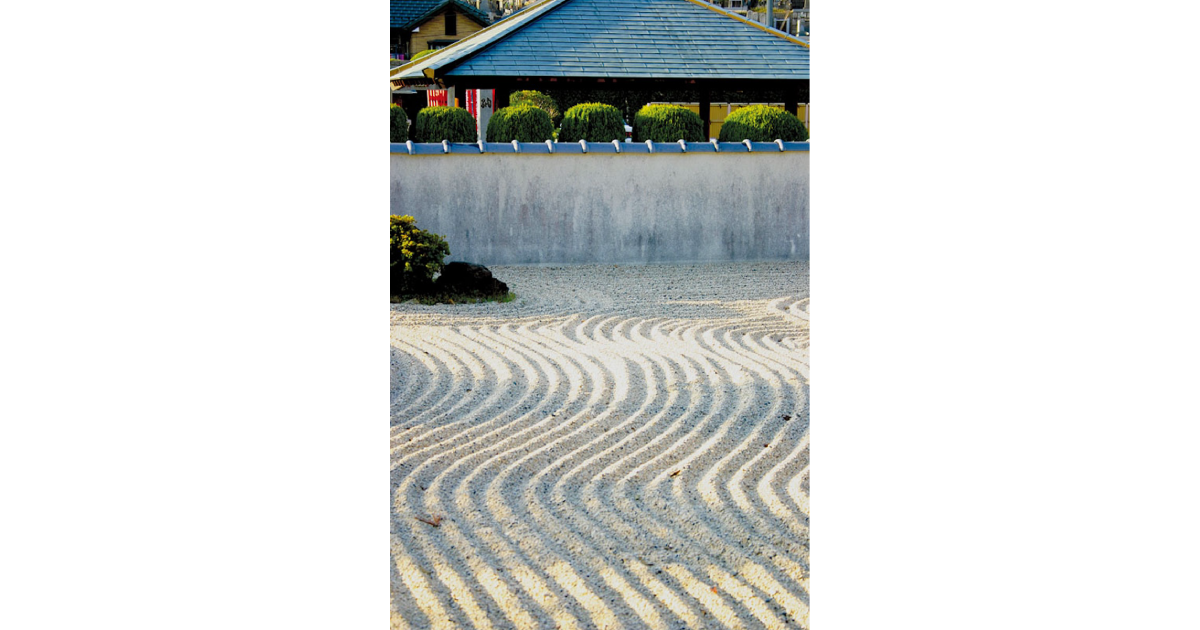

The dominant role played by rocks and stones in Japanese gardens surprises many Westerners, for whom a garden’s beauty is gauged by the number and varieties of its blossom, the more the prettier, to conjure a riot of heady fragrances and dazzling colours. In contrast, a typical Zen Garden has no flowers at all, maybe just a shrub or two, or a miniature pine. What you do get in sekitei, or rock gardens, are great expanses of white gravel, meticulously raked into concentric circles, straight lines or wavy contours – the expanse of shimmering white punctuated with a few strategically-placed rocks. The placement of these rocks is an art unto itself, and a Zen discipline.

So, what’s it all about? Some say that sekitei represent the Inland Sea and its many islands. Others claim that they represent the planets and stars. Some believe they are 3D versions of traditional Chinese ink drawings of jagged mountain landscapes. Still others reckon that they symbolize something far deeper, mystical even. D.T. Suzuki (1870-1966) – Japan’s foremost Zen authority – maintained that Japanese gardens express the spirit of Zen. Whichever you believe, for most first-time viewers the impact is overwhelming. It’s hard to avoid a shiver of awe, a touch of déjà vu even, like a tingling recognition of a pattern that is repeated throughout the universe.

Intuitively, you know you’re in the presence of something profound and powerful, designed “to give the viewer that smack in the face that must happen before reflection intervenes”, as painter Joan Miró said about art. After reflection does intervene, you’re left with the question – just what does it mean?

According to explorer and art historian Langdon Warner (1881-1955) – believed to be the inspiration for Spielberg’s Indiana Jones character – Japanese gardens are designed “to express the highest truths of religion and philosophy precisely as other civilizations have made use of the arts of literature and philosophy”.

The most famous of Japan’s stone gardens is the gravel and rock ‘mind-scape’ at Kyoto’s Ryoanji Temple. It attracts over a million visitors a year, from all over the world. For Shunmyo Masuno, often called Japan’s leading landscape gardener, the garden at Ryoanji is where his fascination with sekitei began. His parents took him there when he was just a boy. “It was a kind of culture shock,” he says, “as if my head had been split open with a hatchet.” Today his award-winning garden designs can be found in office blocks, apartment complexes, public parks and private residences from New York to Norway, Singapore to Latvia. Clearly, Zen Gardens have become a truly international phenomenon.

Sekitei first became popular in the Kamakura Era (1185-1333), following the arrival of Zen Buddhism from China in the late 13th century. These gardens continued to develop in the Muromachi period (1333-1573), a period that also saw a blossoming of Zen-related arts including calligraphy, the tea ceremony, flower arranging and martial arts.

Previously, the gardens of the Heian Era (794-1185) were lavish recreations of Buddhist visions of paradise. Lords and ladies of the Imperial Court would go boating there amid the sumptuous beauty. But in the Kamakura Era, the balance of power shifted and the samurai warrior class rose to prominence. Zen was quickly embraced by the samurai, who identified with its emphasis on simplicity, self-discipline, and the importance of meditation to find one’s true self, undistracted by ostentation and worldly possessions.

Shunmyo Masuno explains the connection between Zen and the arts: “Through Zen ascetic practice an emotion of the mind is found that can’t be directly exposed or understood. One must therefore discover ways to communicate this emotion to others. That is, ‘the expression of oneself’. The Zen Priest has traditionally turned to such classical arts as calligraphy, ikebana, and rock placement.” Aside from his work as a landscape gardener, Masuno is the 18th generation chief priest at Kenko-ji Zen Temple in Yokohama.

Today, Masuno is one of a vanishing breed – a 21st century ishitate-so (lit. rock-setting priests), a term of respect given to Zen priests who design gardens reflecting Zen ideals as part of their ascetic practice, with great importance given to rock placement. Centuries ago, many such priests existed. Today only a handful remain.

“The meaning of Ryoanji’s garden is still a mystery,” says Reina Ikeda, a graduate of Kyoto’s University of Foreign Studies who knows Ryoanji very well. “There are 15 rocks in the garden, but you can see only 14 of them at a time – whichever angle you look from. The number 15 means ‘perfect’ in Oriental culture. The number 14 means ‘imperfect.’ For Japanese people, it’s beautiful precisely because it’s not perfect. This idea is called ‘wabi sabi’.”

Wabi sabi is a concept that finds beauty in rustic simplicity, in objects worn by age, imperfect and transient. It infuses much of Zen art and design. So, imperfection – far from being a negative concept – is an attribute in Japanese culture.

Another key concept in Zen gardens is the abundance of empty space – pristine and uncluttered – a reflection of how your mind should be when you’re meditating. In the West, we are uncomfortable with empty space, just as we are with silence in conversations. We feel compelled to fill both. In Zen, empty space is important, beautiful even, as demonstrated by the two concepts of ma (interval or space) and yohaku no bi (the beauty of emptiness).

According to Mira Locher, architect, educator and author of two books about Shunmyo Masuno (Zen Garden Design, 2020,and Zen Gardens – The Complete Works Of Shunmyo Masuno, 2012,both published byTuttle): “The concept of ma, implies the existence of a boundary, something that defines the interval or space (for example, two columns). In the West, we tend to consider the boundary object(s) ‘positive’ and the space ‘negative’. However, in a Zen Garden, the space (ma) is understood as a positive element, and the garden designer uses the boundary objects to shape it… it is an important element within the garden.

“Yohaku no bi is a device that allows the viewer’s mind to settle down. Unlike ma, which is intangible space, yohaku no bi typically is represented by something tangible, such as a bed of raked white pea gravel. The contrast of the whiteness and uniformity of the gravel juxtaposed against rough rocks or variegated greenery produces the sense of emptiness which in turn allows the viewer to “empty” their mind.”

So uncluttered spaces help unclutter the mind, invoking a kind of meditative state. Indeed, Zen Gardens can be seen as an artistic representation of the mind when it is meditating – a sculpture representing the uncluttered space, the total calm, a stillness unruffled even by storms or gales. This explains why these gardens are so compelling to the eye, yet so elusive for the mind to grasp. Like enlightenment itself. Classical Japanese art forms such as landscape gardening and flower arranging express the Zen experience by taking the mind where words can’t go.

Masuno believes Zen gardens – even a small one – can play a vital role in today’s cities, not only in brightening up the urban environment, but also in helping to “restore people’s humanity”. For those who spend their days working inside buildings, bombarded by information and divorced from nature, garden spaces can help them find balance in their lives by “creating space, both physical and mental, for meditation and contemplation within the chaos of daily life”, writes Locher in Zen Garden Design.

Masuno sees 21st century life as being obsessed with the pursuit of an abundance of things. What is needed to counteract this obsession, he says, is “an abundance of spirit”, a chance for self-reflection and a connection with one’s inner self. This is what he strives to provide with his Zen spaces.

“There is a beauty in Zen gardens that many people find appealing and calming”, says Locher, “… many people are suffering from being disconnected from nature in their everyday lives, and Zen gardens are designed to provide that connection”.

Shunmyo Masuno defines a Zen Garden as “a special spiritual place in which the mind dwells… a place to come face-to-face with yourself”.

Today’s Zen Gardens are continuing a tradition that began nearly 1,000 years ago. By bringing the past into the present, these Zen spaces offer a glimmer of hope for the future.

Steve John Powell & Angeles Marin Cabello

To learn more on the subject, check out our other articles :

N°136 [FOCUS] The essential spirit of Zen

N°136 [EXPERIENCE] Letting go for real

N°136 [TREND] The importance of practicing Zen

N°136 [TRAVEL] Hirosaki, the jewel of Aomori

Follow us !