(C) Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

Often shunned by tourists, Ibaraki Prefecture has many beautiful locations for lovers of nature.

Every year, the Brand Research Institute asks thousands of Japanese to rate the attractiveness of the country’s 47 prefectures. According to the 2021 Regional Brand Survey, Ibaraki came last, as usual (for the record, the top-three prefectures are Hokkaido, Kyoto and Okinawa). Granted, Ibaraki may not be as flashy and exciting as other places. However, it is well worth a visit, especially if you are based in Tokyo.

One of Ibaraki’s must-see places is Lake Kasumigaura, Japan’s second-largest lake. The region centred around the lake is rich in nature and history and is particularly attractive if you are into cycling, fishing or birdwatching. It also has an extremely fascinating geological history.

The Kanto Plain, which comprises Tokyo and its surrounding prefectures, was once located at the bottom of a shallow sea, and what is now called Tokyo Bay reached as far as Ibaraki. During prehistoric times, the effect of climate change was severe due to alternating glacial and interglacial periods (warm periods from one glacial period to the next). The region was often submerged, with mud and sand accumulating at its base. Later, several active volcanoes located not far from the area contributed to shaping the plateau around Kasumigaura. At the same time, the earth and sand carried by the region’s many rivers dammed the space between Kasumigaura and the sea, creating the lakes we can see today. However, the original lakes were closer to an inland sea and were home to many saltwater fish. Broadly, Kasumigaura can refer to the three lakes (Nishiura, Kitaura and Sotonasakaura), which resulted from those geological changes. They are connected by several rivers and canals and have a combined area of 220 km2. However, more narrowly, Kasumigaura refers to the largest of the three lakes, Nishiura (172 km2).

The best access points to the lake are Tsuchiura on the JR Joban Line and Itako on the JR Kashima Line. The latter station is the starting point of our exploration. Itako is called a suigo (water town) because of its canals and the rivers and lakes which surround it. It is also very well known among enka fans as it is the subject of several traditional pop songs. But today we are heading to the lake, so we hop on a hired bicycle and head westward following the wide and peaceful Hitachitone-gawa River. On any weekend, people can be seen fishing, rowing and even practising their waterskiing skills.

Along the way, we cross one of the region’s many flood gates. Japanese rivers are notoriously prone to overflowing and causing disastrous floods during the rainy and typhoon seasons, and Kasumigaura is no exception. In June 1938, for instance, the largest flood in the region’s modern history occurred, submerging vast areas for more than a month. It was followed by another big flood in 1941. This time, it took two months for the water to drain away completely. The floods were caused by heavy rain in the upper reaches of the Tone, the region’s main waterway and Japan’s second-longest river. As a result, a complex system of hydraulic locks was devised to control the flow of water.

These locks have been a mixed blessing and both farmers and fishermen have opposed them. On the one hand, they’ve contributed to the desalination of the lakes. On the other hand, though, they’ve made it easier for seawater to flow up the rivers, causing damage to crops and destroying the habitat where asari and shijimi clams used to live in the brackish water.

To the land side of the cycling road, there’s a long strip of rice fields. Farming is one of Ibaraki’s main economic activities, and rice paddies are everywhere. During the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate began a massive project aimed at recovering and developing the flooded lands by diverting the course of the Tone-gawa River – which originally discharged into Tokyo Bay – eastward into the Pacific Ocean. The project also entailed the construction of an irrigation system that led to the development of rice farming.

If you want to know what this area looked like in the late 1950s, you should watch Kome (The Rice People), a 1957 film by Imai Tadashi, which chronicles the lives of poor farmers who struggle to keep their heads above water and hold on to what little they had while trying to pay off their debts.

DR

(C)Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

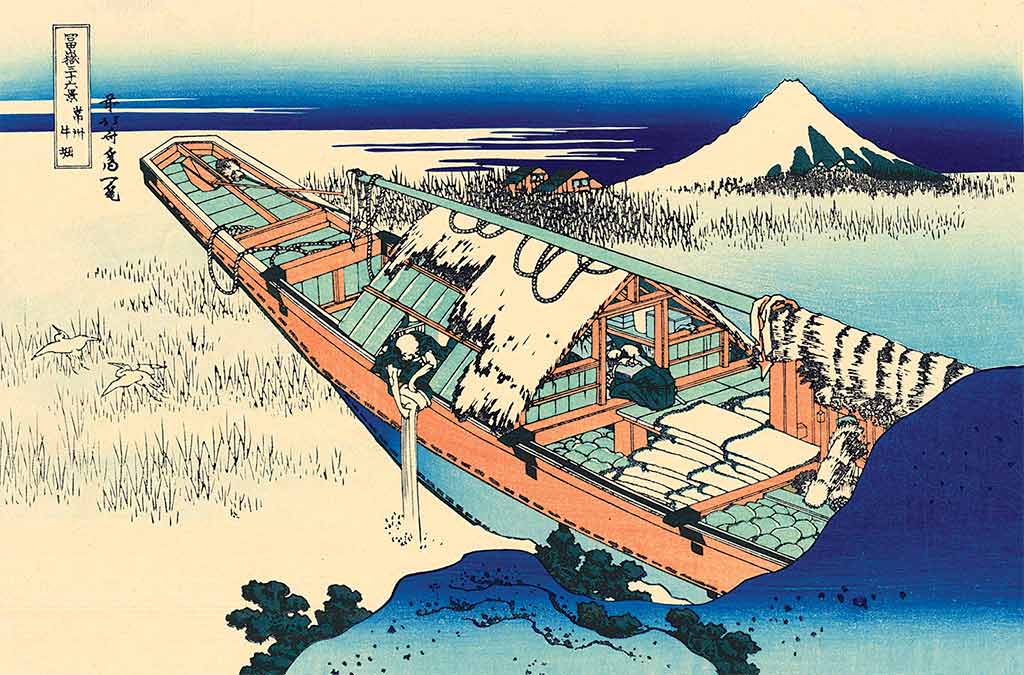

As we come closer to the lake, we pass through Ushibori. This district is also featured in Katsushika Hokusai’s famous Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series of ukiyo-e prints. In the morning mist, a large fishing boat floats above the reedfilled water. The sailors, who have slept on board, have just woken up and one of them is preparing to cook rice. He leans overboard and throws away the rice-polishing water, in the process scaring two egrets which fly away to a quieter place.

This picture showcases two of the area’s main attractions: fish and birds. As we have seen, the process of sedimentation caused by the many rivers in the area turned Kasumigaura into a freshwater lake, introducing completely new species of fish such as wakasagi ( Japanese smelt), shirauo ( Japanese anchovy), carp, eel and shrimp. The lake’s signature fishing boat is a sailing trawler called a hobikibune. Invented in 1880 by a local man called Orimoto Ryohei, these boats were particularly suited to the calm but extensive waters of Kasumigaura, and revolutionised local fishing as they could be operated by just two or three people, whereas the old fishing method required the concerted effort of a team of 20. Hobikibune were so effective that it was possible to haul in about 200 kg of fish on one shift on a single boat. Hobikibune were used in commercial fishing until the late 1960s, when they were replaced by motorboats dragging nets through the water. Today, these beautiful sailing boats are only sporadically operated for sightseeing.

The introduction of motorboats has also contributed to the demise of commercial fishing in Kasumigaura. Though this more efficient system temporarily increased the catch of smelt and other fish, it eventually led to the depletion of fish stocks. Catches have declined rapidly, particularly since the 1980s. In the latter half of the ’90s, for instance, the total catch had decreased to about one-fifth of that in the ’70s. Other reasons for this radical depletion are the reduced amount of plankton (caused by changes in water quality) and the gradual loss of natural lakeside vegetation due to the development of embankments. However, though industrial fishing has been on the decline, amateur fishermen can still enjoy a pleasant outing by boat or along the shores of the lake.

After crossing the Kita-Tone Bridge, we finally reach the lake and keep cycling westward following its southern shore. This part of Kasumigaura is rather narrow, and we can see the northern shore across the glittering waters. The mighty Mount Tsukuba rises in the distance, its imposing blueish shape standing out on the horizon.

The low-lying wetlands close to the lake were developed from the late 16th century onwards when the future shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, moved to the Kanto region. Land reclamation continued at a quicker pace from the 1920s onwards, in response to the food shortage and rice riots caused by World War I.

Pushing our heavy three-speed hired bicycle along the Ring-Ring Road, we are overtaken by a score of road bikes. For those with enough stamina and an adequate bicycle, the Circuit Course is around 130 km long.

(C)Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

We finally reach the Ukishima Marsh and its most popular spot, Myogi-no-Hana, a low-lying wetland famous locally as a birdwatching spot. Its current area is said to be about 52 ha. It used to be larger, but has gradually decreased due to reclamation and embankment construction carried out since the mid-20th century.

Myogi-no-Hana is a typical kayaba (wetland overgrown with reeds, similar to a thatched roof ) and is said to be one of the largest reed beds in the Kanto region. Near the south shore of this nose-shaped marsh there is a hut from which a variety of birds can be observed all year round. In particular, this marsh is known to be a breeding ground for Japanese reed buntings, marsh grassbirds, oriental reed warblers and black-browed reed warblers.

We head back to Itako. If you still have some energy left you should pay a visit to the canal area west of the station (famous for its Iris Festival in early summer) and Chosho-ji, a Buddhist temple founded in 1185 by Minamoto no Yoritomo to pray for his prosperity as a warlord. It also houses many national, prefectural and city-designated cultural artefacts, including a bronze bell from the Kamakura period (1185-1333).

Jean Derome

Getting there

From Tokyo, Itako is accessible in 70 minutes by Express bus. At Tokyo station Yaesu exit, take an Express bus to Kashima Jingu or Kashima Central Hotel, and get off at Suigo-Itako Bus Terminal. From there, a taxi or a free shuttle bus take you to the city center (10 minutes). Alternatively, by train, the JR Joban Line connects Ueno Station to Tsuchiura in about one hour. In Itako, bicycles can be hired from the Tourist Information Office next to the station.

Open 9:30-17:00 (closed on Tuesdays) Fee: 1,000 yen for one day https://itako-cycling.com/rental/

In Tsuchiura, a variety of bicycles can be hired from several places (see link).

https://www.city.tsuchiura.lg.jp/page/ page014976.html

For a more immersive experience and a one-night stay, check out Yamamoto Fujiko cycling tours

https://madam-fujiko.com/tour/