Kutsuna Tomohiko and Kazuko set up the Shiokaze no denwa to keep in touch with lost loved ones.

Faced with a school system unable to accept students who are different, a school in Tahara welcomes and educates them.

The Atsumi Line is a tiny, single track railroad in Aichi Prefecture connecting Toyohashi to Mikawa Tahara Station, 18 kilometres away. Each one of its ten three car trains is painted a different colour and bears the name of a flower. The one on which I was travelling was the green coloured tsubaki (camellia). I had never heard of either Tahara City or the penis shaped Atsumi Peninsula where it is located until I read an article in The Japan Times about Yuzuriha Gakuen (https://yuzuriha-gakuen.com), a non profit organisation that operates an institute for futokoji students who refuse to go to school. As my trip had taken me to Nagoya, I mailed them and they invited me to visit their school. Kutsuna Tomohiko and Kazuko, the school’s founders and principals, have run Yuzuriha Gakuen since 2001. Kazuko used to be a junior high school teacher, but decided to leave her job after clashing several times with the principals about the way the school system treated students, especially people with diverse needs and abilities that did not fit into the mould of Japan’s rigid education system.

The next step for Kazuko was to open a free school with Motohiko, who is a painter. “We started with two students and now have about 80. So far, some 370 kids have finished high school while under our care.” Some of them have been at Yuzuriha Gakuen for 12 years, from first grade all the way to high school graduation. “Each one of them has a story,” Kazuko says. “For us, the best reward is seeing them through school, year after year, overcoming their problems and building their own lives.”

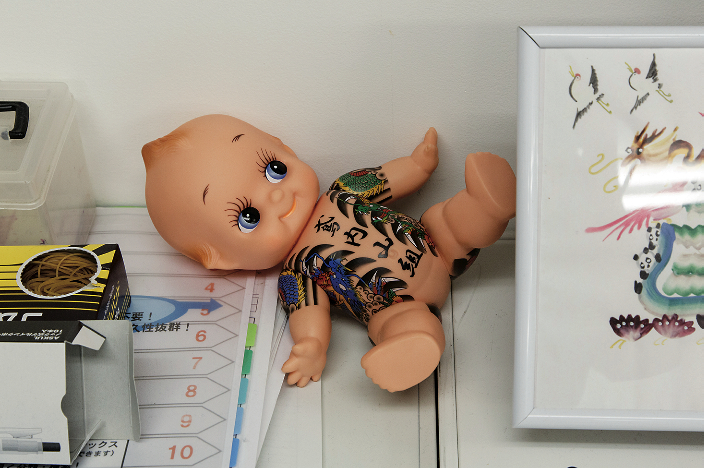

She shows me some beautiful crayon drawings. “This particular girl went on to become a pretty successful painter,” she says. “She drew these when she was in elementary school. Now she must be around 26. I like the fact that they keep in touch even after they leave our school. We often hear from them, for example when they get married or have a baby.

There was one more reason for my visit to Yuzuriha Gakuen: in 2018, in the school grounds, the Kutsunas set up a phone booth with a disconnected black telephone for people wanting to connect with loved ones they had lost. They called it Shiokaze no Denwa (Phone of the Sea Breeze) after Kaze no Denwa (Phone of the Wind), a similar booth built in Otsuchi, one of the cities in Iwate Prefecture that was hit by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. The booth in Otsuchi, created by garden designer Sasaki Itaru in his garden overlooking the ocean, has attracted tens of thousands of people from Japan and abroad seeking to “talk” to those they had lost. My mother’s death, one year earlier, had hit me hard, probably because it had been so sudden and unexpected, and I felt I hadn’t had the time to say goodbye yet, so the following morning I walked into the red wooden telephone booth and called her.

The Kutsunas had their own special reason for setting up Shiokaze no Denwa: they want- ed to be able to remain connected with a student who had taken her life in 2009 when she was 18. “Maki arrived here three years after we opened the school,” Kazuko told me while we sat under the arbour, serenaded by the cicadas. “She was in her second year at junior high. She had Asperger syndrome, and most of her teachers had treated her harshly because they didn’t understand her condition. Even for us, it was a big learning curve.”

By the time Maki came to Yuzuriha Gakuen, she had begun to think about taking her own life. “Eventually, she spent five years with us, but more than once she tried to commit suicide by taking pills, and eventually she succeeded,” Kazuko says. When Maki took her life, the Kutsunas seriously thought about calling it quits. “We had reached our limit, and saw her death as our personal failure,” Kazuko says.

“Then something happened: instead of blaming us for not doing more for their daughter, her parents came to thank us. Our school, they said, had given Maki five more years of life. I guess they understood our feelings, so they urged us to continue. And so we did.” Every now and then, Kazuko and Motohiko go into the booth and speak to Maki. “I feel like she’s still here,” Kazuko says.

After lunch, they drove me to Irago Cape, on the tip of the Atsumi Peninsula. It’s an idyllic sight, but Motohiko warned me that the strong ocean waves can be lethal if you are not careful. It’s time to say goodbye. I can’t help but admire people like Kazuko and Motohiko who manage to tackle such hard psychological and mental problems and support all those young people and their families. I can only imagine their job’s emotional toll. Then again, calling it a job is misleading. It’s a mission, pure and simple, born from an acute awareness of society’s failure to support those people who don’t conform to certain behavioural expectations. I will always remember our meeting and my phone call to my mother.

I finally took a seat on the ferry and resumed reading The Adventure of Huckleberry Finn. I later found out that Mark Twain’s mother died when he was 54 years old – the same age I got the phone call from my sister telling me that our mum had left us.

G. S.