The microbrewery uses three brewing systems (60,10 and 2.5hectolitres respectively).

The microbrewery uses three brewing systems (60,10 and 2.5hectolitres respectively).

Journalist Noda Ikuko’s discovery of beer mirrors the Japanese encounter with this drink.

While Japan has been in love with beer for more than a century, most people know little about the vast and varied beer-making scene that exists outside the pilsner style that still rules the domestic market. In 2010, to remedy the problem and educate the public, a group of beer experts and writers established the Japan Beer Journalists Association (JBJA). members of this loose organisation collect and share beer information, visit breweries, cover beer events, and host work- shops and tastings. Zoom Japan talked about the Japanese beer scene with JBJA’s vice chair- woman, Noda Ikuko. Besides teaching at the Beer Journalist Academy, Noda writes for several magazines including Beer Okoku (Beer Kingdom) and has edited and written various beer books. A staunch supporter of craft beers, Noda has been trying to convince the Japanese for more than ten years that there is a huge exciting world outside the narrow domestic Pilsner mar- ket, and that beer can be enjoyed in many different ways. “when people think about beer, especially during the hot and muggy Japanese summer, they can only come up with one image: grabbing a cold beer and a plate of fried food at a rooftop beer garden,” she says. “But a chilly beer in summer is not the only option available. there are many different kinds of beer out there, and some can and should be enjoyed at warmer temperatures. then, of course, there are chocolate or banana-flavoured beers, and some that are as sour as vinegar. that comes as a shock to many people here.”

Noda’s life has been a slow journey of discovery as she has gone through several shocking experiences herself on her way to beer enlightenment. “I clearly remember my first beer,” she says. “my father used to drink beer every night. He would start drinking while my mother was still cooking dinner, even before our family of seven assembled around the dining table. He always drank Kirin Classic Lager, without fail. It was definitely in a bottle, not a can. my grandfather preferred hot sake, but for my father, nothing beat drinking beer with salted squid.

“As I watched this scene every night over many years, I told myself it looked delicious even though I was just a child. So after graduating from high school, I decided to give it a try. one night, my friend came to stay at my house. I waited for everybody to fall asleep then I sneaked into the kitchen and took one of dad’s beers from the fridge. After one sip of the cold liquid, my friend and I looked at each other, our eyes wide open with surprise, and we exclaimed, “it’s good (laughs)!” I just loved beer’s bitter taste. I guess loving booze was already in my DNA. After all, I come from Yamagata Prefecture. Anyway, that night I thought, I’m an adult now!”

The next step in Noda’s beer education came through manga. “I can’t explain why I love beer without mentioning FURUYA mitsutoshi’s Bar Lemon Heart,” she says. “I started reading it in the early ’90s. this manga is a bible for every booze lover. the main characters are the bar- tender of the bar in the title and a couple of regular customers, one of whom has zero knowledge about alcohol and such things. this comic covers all kinds of drinks, of course, and I had a chance to learn a lot.

“In one episode, matsu-chan, one of the customers, drinks a cassis-flavoured timmermans. that’s how I first learned about the existence of Belgian beers. moreover, I was surprised that beer could contain fruit. At the time, you couldn’t really find that kind of beer in Japan. After reading that manga scene, the doors of intellectual curiosity opened in front of my eyes.”

Noda eventually drank timmermans at a Belgian Beer Fair held at Printemps ginza, a tokyo department store. “I had developed a little bit of an obsession for that cassis beer, so I snapped one up as soon as I saw it,” she says. “then I bought another one whose label was decorated with a stained glass motif, which I love, and went home to drink them on my balcony. For me, drinking beer while reading something on my balcony is the perfect way to have a great time.”

The second beer, which Noda had bought on a whim, proved to be another eye-opener. “once again I went wow, what’s this? It had a deep fruity feel like ripe figs and was a little bit spicy. that was my first encounter with Leffe radieuse, a beer made in one of those Belgian monasteries. I had only bought it because it had a lovely label, but I discovered an entirely different world; a spicy beer with a very complex taste, with notes of orange rind and coriander seeds.” Noda was so affected by that experience that she decided to visit the place where such incredible beers were made. “I was planning to go to England and France on holiday for two weeks,” she says, “but I immediately called the travel agency and asked them to include Belgium in my trip. Some experiences are so powerful that they make people change their behaviour.”

Noda’s third formative encounter was with draft beer. “I think it was around 1996 or ’97,” she says. “I found a bottle of ginga Kogen beer. Again, I bought it mostly because of its label – a cute reindeer – but I certainly didn’t regret my choice. First of all, I was surprised by its soft, sweet banana flavour. It’s a german-style white beer, and I later learned that it was made with wheat. I realised that even in Japan one could find delicious beer, neither too sweet nor too bitter.”

“A new kind of place has appeared, which provides a complete experience by creating a space where you can enjoy good beer and food, and hospitality”..

“A new kind of place has appeared, which provides a complete experience by creating a space where you can enjoy good beer and food, and hospitality”..

After graduating, Noda found a job as a hotel receptionist, but with the arrival of the internet she realised that working with computers would give her the freedom to work wherever she wanted. “when I talked to a friend about my aspirations, she pointed out that I liked books and magazines, so I should become an editor. And so I did,” she says.

Noda found a part-time job at ASCII (now called ASCII media works), a company that specialised in computer magazines. “I worked at MAC People, a publication devoted to Apple products such as the macintosh and was aimed at beginners to intermediate users,” she says. “Nowadays, desktop publishing (DtP) is the rule, but at the time, ASCII’s magazines were the only ones that used DtP so they were really cutting edge.

“my first chance to be involved in beer-related work was the series Let’s meet at the bar by the same magazine, which became a series in around 2003/2004. we would meet people from the It industry to talk about their work over a beer or two. then a former colleague who knew I loved beer said that he was planning to compile a book on the subject and asked me to contribute. that book turned into the series called Let’s drink the finest beer.

In those years there was a particular interest in foreign beers, but local microbreweries were mostly overlooked. “I began researching stores and bars that specialised in Belgian, german and other foreign brands,” Noda says. “I think the major turning point regarding people’s awareness of local craft production was the Craft Beer market chain that opened in 2011. Suddenly, you had several places that were offering good food and beers nobody had tasted before, and at reasonable prices. It created a lot of talk and attention around the craft beer movement. thanks to this chain, the number of new beer drinkers has also increased significantly.

“From a business point of view, craft beer cannot be said to have a high-profit margin because of the high production costs. And when it comes to foreign beer, you have to add import expenses. But this bar introduced a system of uniform, two-tier prices (currently it’s 490 yen (£3.62) for a glass and a very competitive 790 yen (£5.83) for a pint), which is relatively inexpensive for the Japanese market. From that starting point, the number of craft beer bars has increased very quickly.”

According to Noda, this revolution is gradually changing the beer pub industry. “without any doubt, it’s been a big trend for the past few years,” she says. “A new kind of place has appeared, which provides a complete experience by creating a space where you can enjoy good beer and food, hospitality, and a continually changing lineup of new suggestions. It’s a new philosophy in that customers are encouraged to interact with the owners who are always happy to advise them about choosing the right beer.”

Currently, there are more than 400 microbreweries in Japan, and the craft beer market, though still very small, is constantly growing. “the current boom began in 1994, when the government relaxed its tax laws,” Noda says. “However, many of the craft beers or jibiiru (local beers) as they were called – produced until the turn of the century were expensive and pretty bad because a lot of brewers lacked the necessary experience and knowhow. It was the kind of novelty beer tourists might be tempted to buy as a souvenir, but would never make the mistake of buying a second time.

“Things began to change about 10-15 years ago when Japanese brewers began to enter their products in international competitions, but the real turning point happened in 2015 when Japan’s four major companies started investing in brewing craft beer. Beer sales had been shrinking for several years, and the Big Four needed a new product that differed from the usual Pilsner style that had dominated the market since the beginning of the 20th century. Kirin, in particular, has led the way by cooperating with local microbreweries and sharing its long experience and huge technical knowhow. this collaboration has contributed in considerably increasing the average quality of domestic craft beer.”

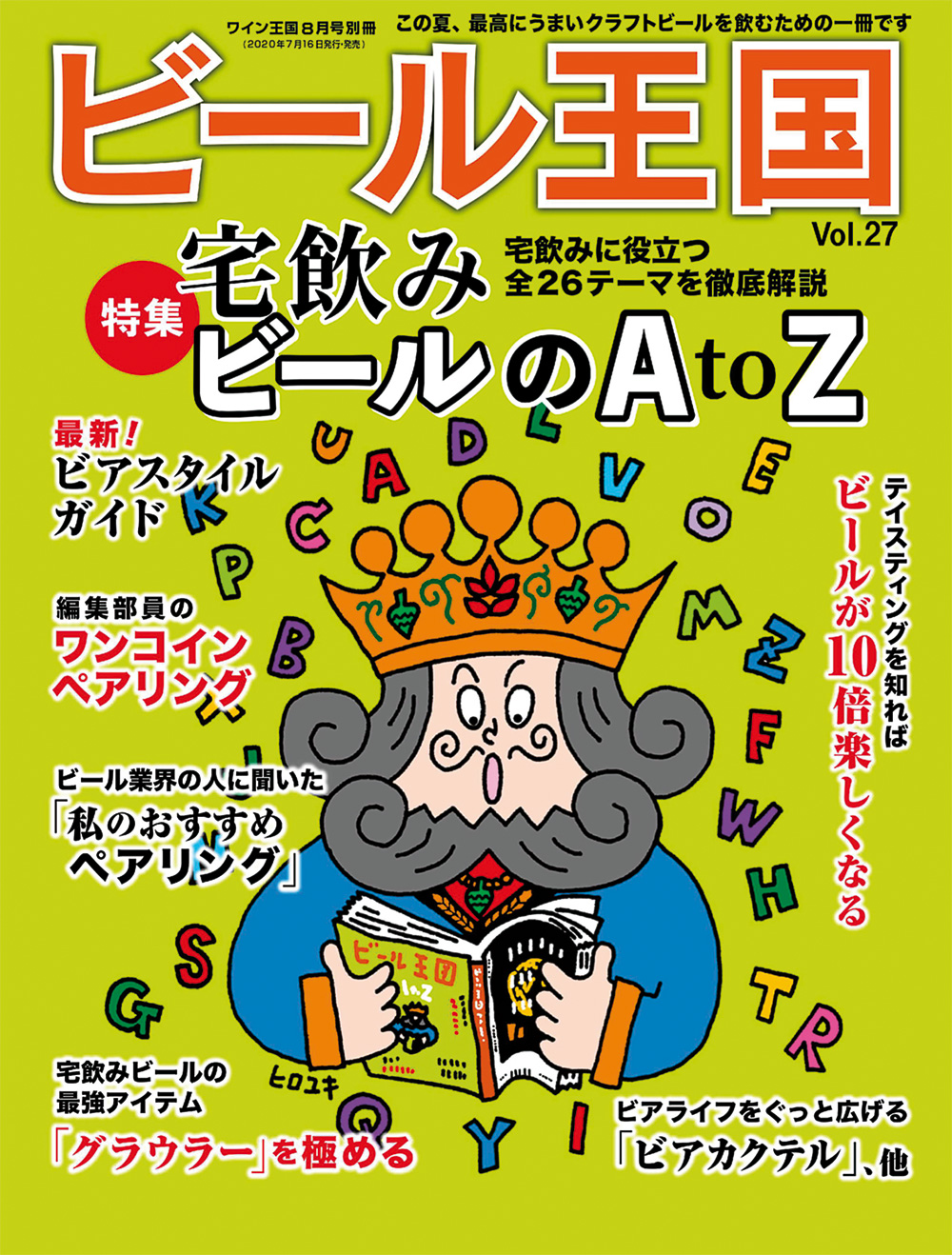

Founded in 2013, Biiru Okoku is the bible for beer lovers in the Archipelago.

Founded in 2013, Biiru Okoku is the bible for beer lovers in the Archipelago.

Noda is very hopeful about the role that Kirin, Asahi and the other major brewers can play in diversifying the domestic beer market. “think about what they did with happoshu and “new genre” beer,” she says. “on the one hand, the Big Four deserve a lot of respect for creating these wildly popular new beverages. However, I think it’s a pity they used their experience and superior technology to develop something like happoshu. After all, it was only created to avoid the punitive alcohol tax. If you ask me, they could have put their skills to much better use. moreover, this new category has created some confusion, because there are some foreign beers – real beers – that in Japan are labelled as happoshu only because they contain coriander or fruit and have a low alcohol content.”

According to Noda, the other significant thing that has happened in the last few years has been a change in attitude in the craft beer industry. “originally, beer-making was imported from abroad,” she says. “Even the whole craft beer concept was born in Europe and later adopted and further developed and made cool by American brewers. As for Japanese brewers, for many years they were content with just copying foreign beer-making, whether it was in the British or American style. But in the last few years they’ve learned to introduce original brewing methods and local ingredients such as Japanese herbs, seaweed, etc. one type of beer Japanese brewers do very well is fruit beer. Each region is famous for a certain fruit, and beer makers use them to their advantage. Peaches, natsu mikan (bitter summer oranges), grapefruit, you name it. Japanese brewers are very good at striking the right balance between a beer’s characteristics and fruit to complement it.”

When asked what she likes the most about her job, Noda says it is the beer itself, but she’s quick to add that other elements are equally important. “I like the act of choosing different beers depending on the situation,” she says. “where I’m drinking, with whom, what I’m eating with that beer; all these things must be taken into consideration and, for me at least, it makes the whole experience even more fun and interesting. when you think about it, beer is a sort of communication tool. Choosing a beer is a very subjective thing; it’s a way both to get to know yourself and the people you’re drinking with. It’s fun to see what other people drink, what choices they make.”

Noda loves drinking in bars and pubs because the concept behind each one is different, and thanks to the bartenders’ knowledge and friendliness she always gets to discover wonderful new brands. Unfortunately, CoVID-19 has seriously curtailed her outings, but she’s trying to help the industry as much as she can. “I often buy directly from the breweries,” she says. “I confess I haven’t been to a bar for a few months now, but I’ve bought a five-litre container and I get it filled at the bar so I can keep drinking on the safety of my veranda with my husband. It’s the least I can do to support people involved in beer… and my drinking habits (laughs).”

Apart from beer, Noda has other hobbies including scuba diving, and relishes the opportunity to combine these two passions whenever she can. “Baird Beer built a factory in Shuzenji, Shizuoka Prefecture, in 2014,” she says. “Shuzenji is a hot spring area on the Izu Peninsula, and Izu is a mecca for diving. So for me, a trip there is a chance to enjoy scuba diving in the morning, a dip in the hot springs in the evening, and excellent craft beer at night. It’s the full package!”

J. D.