The microbrewery uses three brewing systems (60,10 and 2.5hectolitres respectively).

The microbrewery uses three brewing systems (60,10 and 2.5hectolitres respectively).

Founded in 2000, this microbrewery’s high quality produce has been successful in Japan and abroad.

The Izu Peninsula just south of Tokyo is popular for its beaches, hot springs and gorgeous nature. Since 2014, it has been attracting a new kind of fun seeker: beer lovers. that’s because microbrewery Baird Beer moved its headquarters to Shuzenji, a famous hot spring resort surrounded by rolling green hills in the central region of the peninsula.

Besides the company’s offices and beer factory, the massive Brewery gardens Shuzenji feature a large area full of fruit, vegetables and, most importantly, hop plants, all grown and harvested by the employees. the aforementioned beer lovers, though, usually skip the scenery and head directly to the third-floor taproom where 12 Baird beers are served year-round alongside a selection of three or four seasonal beers an amaz ingly wide and varied lineup. Shuzenji, moreover, is just one of nine taprooms (including one in Los Angeles) that the company either runs directly or has licensed to partners.

A tour of the factory reveals an area where the microbrewer’s artisanal ethics have been espoused, as well as the latest technology to get things done more quickly and more effectively. their original milling machine, for instance, could mill about 2 kilogram of malt in 10 minutes. the current one is able to mill about 12 kilogram in just one minute. they have three brewing systems (60, 10, and 2.5 hectolitres respectively). the biggest one is only semi-automated, which means that someone still has to load the malt at the bottom of the machine. Fresh hops are stored in a different area. In many breweries in Japan, hops are desiccated and then compacted into pellets. the problem with this practice is that they lose some of their characteristics, so at Baird they only use fresh hops.

the hop pit is an ingenious machine that looks like a giant tea strainer and allows the brewers to add various flavours, such as oranges for their Carpenter mikan Ale. the bottling plant is also semi-automated. the bottles are still loaded on by hand, but from that point on, the cleaning, labelling, filling and capping are all automated. with the ability to do all these operations in less than a minute, the Baird Beer brewery can bottle over 100 beers a minute.

Founded by American-born Bryan Baird and his wife Sayuri in 2000, Baird is the typical success story of a once tiny company that has made it big (at least in microbrewery terms).

When it was founded, Baird was the smallest li- censed brewery in Japan – actually more a nano- brewery than a microbrewery – but it has gradually expanded to the point that today it has nearly 100 full and part-time employees and has arguably become the best-known microbrewery in Japan. However, as they say, their start was anything but easy. “when I came to Japan after finishing grad school in the States, craft beer or jibiiru (lo- cal beer) as it was called at the time – was getting a lot of attention,” Baird says. “the government had just deregulated the beer industry and hundreds of microbreweries and brewpubs were pop- ping up everywhere. though I’ve never been a home-brewer, I’ve always been very passionate about craft beer and decided to give it a try.”

In 1997, Baird quit his office job in Tokyo and enrolled at brewing school in the U.S. where he completed an intensive 11-week apprenticeship programme in brewing science and engineering. “Back in Japan, I felt I needed more practical experience, so I cobbled together a tiny brewing system out of used kegs, set it up on our veranda and began brewing pilot batch after pilot batch. this was the actual system with which we launched our original brewery-pub. It was so tiny (30-litre batches) that I had to brew very frequently, and this helped me gain invaluable experience in a very short time.”

However, by the time Bryan and Sayuri opened their original brewery-pub in Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture, the tide had changed and the initial interest in jibiiru had been replaced by a generally negative attitude towards a product that was pretty bad in most cases. “our first big problem was how to overcome the largely negative image that the industry had garnered for itself in those early years,” Baird says. “the other major challenge was simply that we were brewing a kind of beer that had never really existed in Japan before, and people didn’t know what to make of it. Japan is a conservative, relatively conformist society, and going against the grain is difficult. It’s true that the Japanese are very curious about food, but when it comes to beer, there’s an established preconception that beer equals light fizzy Pilsner. Back in the day, the Japanese learned beer-making from the germans, and for about a century, Pilsner was the only available kind in this country. So if you produce something with more character – let’s say ales inspired by the English, Belgian or American craft brewing traditions, you are basically running into a wall.”

Baird is one of very few brewers in Japan that uses secondary fermentation, where additional food sources for the still-active yeast in the unpasteurised beer are added to bottles and kegs. “As the yeast feeds on the sugars, it gives off gas, creating a natural, mild carbonation,” Baird says. “I much prefer this method to directly adding carbon dioxide, but the Japanese are used to heavily-carbonated Japanese lagers, and some of my early customers were utterly confused.”

Bryan and Sayuri opened their original taproom in a blue-collar fishing town where customers only wanted to drink an ice-cold Pilsner. they quickly realised that if they wanted to succeed, they had to create a market out of nothing. “Unfortunately, having a great product is not enough,” Baird says. “the other key factor in growing sales in a nascent market like craft beer in Japan is constant consumer education. the more consumers understand what you are doing, and why, the more open they are to the experience. this sort of education, though, takes time and requires persistence.

“That’s why we started as a brewery-pub. First of all, on the economic side, we had such a small production capacity that selling our beer wholesale was not enough, and we wanted to keep the entire retail profit margin. But more importantly, we were determined to brew a very flavourful beer, full of character, and we knew that other bars and pubs would either not touch our beer or would have a difficult time selling it to their customers.”

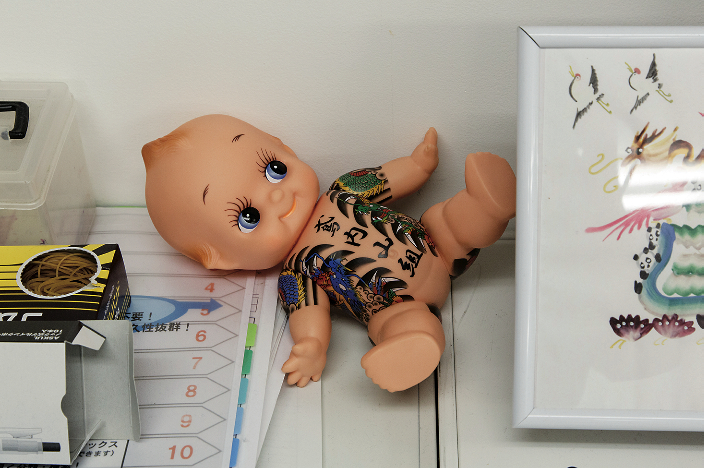

In 2003, the company moved up to a 250-litre system and began bottling beers to sell to increase revenue. one customer introduced the Bairds to NISHIDA Eiko, the graphic designer who would go on to create the distinctive artwork found on Baird Beer’s bottles.

The beautiful labels on the Baird Brewery bottles were created by the artist NISHIDA Eiko.

The beautiful labels on the Baird Brewery bottles were created by the artist NISHIDA Eiko.

The company continued to grow, expanding to a 1,000-litre batch brewing system in 2006 and opening its first Tokyo location, the Nakameguro taproom, in 2008. the same year, Baird also began exporting its beer, first to America, and then to several additional countries.

Finally, after ten years in the business, the microbrewery began to gain real traction and achieved a certain amount of security. In 2010, their efforts were also recognised internationally when they were awarded three gold medals at the annual world Beer Cup.

Despite the evolution of Baird’s brewing processes, the beers they make have largely stayed true to their original recipes as Bryan maintains creative control over the recipes.

“To me, each of the beers we make tells a story,” he says. “Some of them commemorate historical events. one such beer is the Kurofune (Black Ship) Porter which represents the arrival of the American fleet led by Commodore Perry. my father was a history professor and has instilled a love of world history into me. the origin of other beers is closer to my family history and personal experiences. the Kabocha (pumpkin) Country girl, for example, is dedicated to my mother, who grew up in the countryside growing pumpkins.” Baird Beer’s lineup shows David’s original approach to beer-making. the Wabi-Sabi Japan Pale Ale, for instance, is flavoured with wasabi and green tea and is the perfect example of their brewing philosophy. “If I think the flavour will suit my beer and can be made with subtlety and balance, I’ll try to make something with it,” Baird says. their Asian Beauty Biwa Ale and Shizuoka Summer mikan (made with Japanese apricots and oranges respectively) also reflect this. “All these beers are finely balanced to not overpower one particular flavour. when I finished brewing school in 1997, American brewers hated fruited beers because they saw them as just a cheap way to attract new customers. It was just putting some raspberry extract into a wheat beer. I came from that mould, and my brewing philosophy is about minimal processing in terms of hops and barley. But that doesn’t mean you cannot add other ingredients, even fruit, as long as they are natural, in season, fresh, and they are put through the fermentation process. the end result is a beer where the extra ingredients only add a subtle flavour. the last thing you want to do is to be confused with those “souvenir”

flavoured beers catering to tourists.”

For Baird, good craft beer is all about character, and character comes from the interplay of balance and complexity. “Poorly made craft beer tends to be complex, but it lacks balance,” he says.”great craft beer possesses both balance and complexity. For us, the key to achieving this character is minimal processing. therefore, we begin by selecting ingredients that are minimally processed (e.g. barley, whole-flower hops, fresh whole fruit, etc.). then we use these ingredients in as simple and unprocessed a way as possible. For example, we do not filter our beer and we naturally carbonate it in the container through secondary fermentation, much like Champagne.”

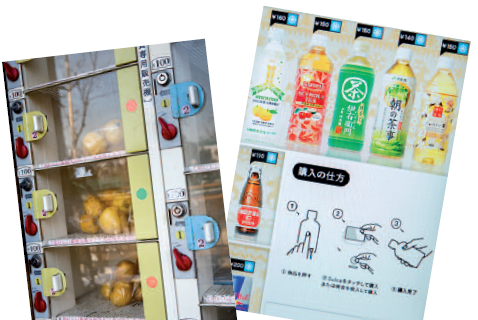

Though craft beer’s share is still a tiny 1% of the national market, Japan has a vibrant local scene that is slowly but surely gaining new fans. tasting craft beer in this country may still be a hit-and- miss experience, but nowadays the movement is not considered a joke anymore. Still, Baird thinks that compared to other countries, Japan poses many difficulties for would-be commercial brewers. “First and foremost, in Japan the tax on each litre of beer is 220 yen (£1.62), one of the highest rates in the world,” he says. “this adds 77 yen (£0.57) to each can of beer. But the most formidable obstacle is the licensing process. Japanese bureau-crats exercise a tight control through their licensing system. the process takes a long time (in our case, approximately one year) and is somewhat subject to the arbitrary unwritten whims of the bureaucrats. on the upside, once the brewing licence is issued, they have a very hands-off attitude and are non-intrusive in their dealings with brewers. Also, in Japan you hardly ever find that pseudo-moral prohibitionist-type of sentiment regarding alcohol that you might find elsewhere.” technical and economic issues aside, craft beer is and will always remain an inherently niche market. Even in bigger markets with a longer tradition, like in America, the craft beer sector is barely able to grow beyond 10% of the overall beer market. “As soon as you put real character and complexity into a product – any product for that matter –you’re putting a limit on how many people you can reach,” Baird says. “this is a problem, especially in a country such as Japan, which is dominated by the same kind of light Pilsners. that’s why a market for craft beer de- pends on education. Japanese retailers, for ex- ample, haven’t recognised yet that the craft beer market is expanding and is worth investing in. we are introducing real diversity and a unique local element into the beer market in Japan, which is a major departure from the approach of the industrial brewers.”

However, at the end of the day, the biggest barrier to craft beer going mainstream, according to Baird, is a lack of truly outstanding brands. “more Japanese brewers may be taking medals and accolades at international events such as the world Beer Cup, but too much craft beer in Japan is still pretty mediocre,” he says. “In order for micro-brewers to be taken seriously, the ocean of so-so craft beer needs to evaporate, and more really well-balanced and characterful beer needs to be produced and marketed. Un- fortunately, the typical Japanese craft brewery is tiny with a very small market footprint. this impedes market reach.”

Baird’s view of the local craft beer scene is far from positive. “the Japan craft beer industry has been around for 25 years now, and we have been a player for 20 of those years,” he says. “while there are pockets of excellence and vibrancy within the community here, the overall picture is rather bleak, particularly now with the CoVID-19 situation.” An unexpected boost to micro-brewers may come from the Big Four beer companies (Asahi, Kirin, Sapporo and Suntory), which have recently started investing in research and coming up with their own craft beers. “they say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” Baird says.” After all, craft beer brings with it a certain sex appeal that interests the industrial brewers. this said, I would call their beer “crafty” rather than real craft beer. mainstream companies got into craft beer only for economic reasons. they saw that the core industrial lagers were not selling as well as before because the population was shrinking and people were drinking less so they decided they had to do something about it. But putting a “craft” label on your beer is not enough. the craft beer these companies are making tends to be well balanced but lacks complexity. In the end, craft is about real creativity, real craftsmanship and authenticity. on the other hand, major beer companies like to play it safe. It’s just not in their DNA. we compete on character, flavour, and personality. Industrial brews have to appeal to everybody. As a craft brewer, you don’t. In the end, craft brewers and industrial brewers are distinct animals. I don’t believe we are in direct zero-sum competition.” Bryan Baird may be leading the craft beer revolution, but he knows all too well that resting on his laurels and enjoying his hard-earned success is the last thing he can afford to do, especially during these difficult times. But a weak national market and coronavirus-related problems aside, Baird Beer remains committed to spreading its name and passion for beer around Japan and beyond.

G. S.