Women played a key role in the development of the consumer society in Japan

Thanks to women’s magazines, people can understand the extent to which the role of women has improved in society.

For many years, women have been key players in Japan’s consumer culture, and they are undoubtedly the country’s biggest spenders. Frequently excluded from decisionmaking in politics and industry, Japanese women have become leading players on the consumer scene, and the media have provided them with the means to become trendsetters, assert their identity and make sense of their lives while exploring such issues as love, sexuality, age, family, food and fashion.

In this respect, women’s magazines are the perfect window onto the world of women, as they help highlight the paradoxes in their lives as they are continually caught between the influences of East and West, tradition and modernity, continuity and change.

Even a rapid tour round a bookshop reveals rows of shelves exclusively devoted to women’s magazines, with separate areas devoted to issues for teenagers, people in their early or late 20s, married women with children, and single career women. The only thing most of them share is that the women typically depicted in these publications are well-educated Tokyoites; they represent the ideal that all Japanese women wish to emulate.

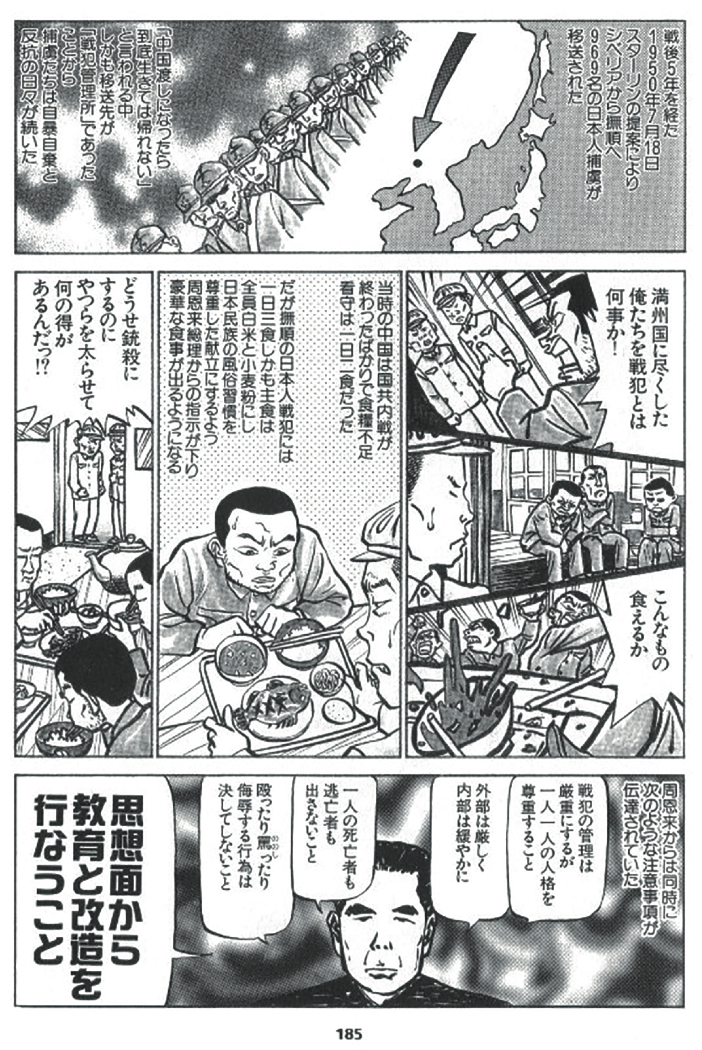

Japanese women’s magazines have gone through different historical phases. The first, which covers the first half of the 20th century up to the end of the Second World War, saw the appearance of such monthlies as Fujin Gaho [Illustrated Women’s Magazine, 1905], Fujin Koron [Women’s Opinion, 1916], Shufu no Tomo [Housewife’s Friend, 1917] and Fujin Kurabu [Women’s Club, 1920]. Except for the more liberal Fujin Koron, these publications aimed to educate women about how to be “good wives and wise mothers”.

In the postwar period, from 1946 to the first half of the 1950s, Japan experienced rapid economic recovery, and people began to aspire to a better material life. A new brand of magazine such as Shufu to Seikatsu [Housewives and Life, 1946] and Fujin Seikatsu [Women’s Life, 1946] abandoned the educational approach of their predecessors to focus instead on providing practical advice on various aspects of household management, with increasing use of photography. From the second half of the 1950s to the late 1960s, weekly magazines began to appear that focused on the private lives of pop stars and actors. However, the major trend of the period was the creation of larger women’s magazines, purveyors of dreams of a richer life. These often sported foreign names like Misses and Madam, and began to show their readers how to enjoy life. For instance, while older magazines taught women how to make dresses, the new ones emphasized buying them. The change became apparent even in the kind of advertising featured in these magazines: household products began to be replaced by fashion, accessories, and leisure as readers were increasingly seen as individual consumers.

The top rated magazine in this category was Katei Gaho [Illustrated Home Magazine]. Launched in 1958, this periodical targeted upper- class housewives in their 40s whose children were at least in their teens, which gave them more time to devote to the aesthetic pleasures of cuisine, fashion and home interiors. Katei Gaho was strongly influenced by the American magazine Life, and its first appearance was a sensation as there were no fully illustrated magazines on the Japanese market at the time. Katei Gaho excelled in presenting a particularly luxurious and tradition-oriented style with an air of exclusivity, sophistication and high social achievement. It was also a typical example of the role played by some magazines in preserving traditional culture. Women were seen as the keepers of traditional arts (e.g. the tea ceremony and flower arranging), which is interesting to note as these arts were once performed by men (even samurai) and were quintessentially masculine in tone. The women featured in Katei Gaho’s pages seemed to be living in an idealised past as they often wore kimono, a garment that by that time was being relegated to rare social engagements. In this respect, the magazine can be seen as a stronghold of conservatism.

This was still a time when young women were encouraged to learn these once elite arts to enhance their value on the marriage market, preparing them for what cultural sociologists Lise Skov and Brian Moeran have called “a married life of idle boredom”. Indeed, even today, though mastering the traditional arts is no longer required to land a husband, it is thanks to women that they survive due to their attending the many cultural centres scattered all over Japan.

The 1970s brought about a revolution in the publishing industry with the appearance of such magazines as An An (1970), Non-No (1971), More (1977) and Croissant (1977). Japan was going through a time of high economic growth, and traditional gender categories began to break down as the number of women going out to work increased dramatically. From being part of the family, women began to be seen as individuals with their own needs and interests, and as their disposable income kept growing, they became interested in travelling and eating out, compelling the new publications to devote more space to these subjects.

Titles like Croissant were labelled as “new family magazines”, a term referring to those belonging to the “baby boom generation”, who were then in their late twenties and were expected to form a new kind of family.

In addition, 1975 was designated International Women’s Year, and Japanese media started focusing their attention on the so-called “flying woman” (from the American bestseller Fear of Flying by Erica Jong), in search of a new lifestyle that differed from traditional Japanese values. It was during the 1970s that the proportion of advertisements in women’s magazines increased drastically: by 1979, the total number in the main 78 magazines exceeded 100,000 pages. Among six of the major titles, the proportion of pages devoted to advertisements ranged between 25% and 55% (An An). To this, we have to add “advertorials”, promotions disguised as editorial material.

The dependency of magazine publishers on advertisements increased significantly as advertising revenue grew 2.46 times between 1976 and 1985. In the same period, revenue from the sale of magazines grew only 1.86 times. Generally speaking, the editorial line in many women’s magazines was, and still is, considered rather weak as tie-ins dominate their content, especially as far as fashion is concerned. Japanese magazines traditionally gather information about their readers through surveys to get a deeper insight into their lifestyle, economic status and attitudes toward a wide range of topics. The magazines pass the results on to the advertisers – they are then both able to fine-tune content to reflect their target groups more accurately.

In the 1980s, Prime Minister NAKASONE Yasuhiro’s “grand design” for an internationalised Japan resulted in the liberalisation of financial markets and a consumer boom with city-based women at the forefront. By 1982, half of all married women were working, and many other aspired to do the same. The 1986 Law of Equal Employment Opportunities did very little to improve women’s status on the labour market, but the debate on gender equality brought to the fore ideas of independence and individualism, and the principle that women should be able to do what they really wanted.

In the first three postwar decades, the Confucian values of endurance and hard work, and the idea that people should sacrifice their own desires for the collective good, still dominated Japanese society. However, in the 1980s consumerism came to be viewed in a positive light. Unmarried women, in particular, having been marginalised in the political and economic arena, came to the conclusion that they could enjoy life to the full as well as spend their own money on fashion, leisure and culture.

Women even moved into areas of consumerism which until then had been the domain of men. Young women began to ride motorbikes, go to bars, play golf and bet on horses. They were promptly nicknamed oyaji-girls (uncle or middle- aged girls).

In this period, the importance of magazines in Japan’s publishing industry as a whole reached an all-time high. As many as 1,300 new magazines were launched or re-launched between 1980 and 1985, and while sales of books had fallen since 1945, sales of magazines continued to rise. Women’s magazines were among the big winners with average circulations of several hundred thousand copies. The king (or maybe queen?) of the pack was Non-no, a magazine aimed at 12 to 19-year-old girls, that sold a jawdropping 1.3 million copies.

The early 1980s were also notable for the launch of Japanese editions of Western magazines such as Cosmopolitan (1980) and Marie Claire (1982), while many local titles sported Western-sounding names: 25ans (1980), Lee (1983), Vivi (1983), Classy (1984), Sophia (1984) and Ef (1984).

The increase in segmentation and new trends in the publishing market shortened the span of each phase in the history of Japanese magazines: the sixth period only covers 1985 to 1989. During this time, the magazine market became dominated by titles targeting unmarried women in their late 20s and 30s, the so-called “elite cosmopolitans” of the bubble era. These were women who worked hard and played hard, travelled abroad, and bought expensive brandname goods – sometimes even travelling as far as Italy and France, alone or in organised groups, with the exclusive purpose of engaging in binge shopping. While occupying subordinate positions in the workplace, these women were nevertheless earning a good enough salary to let them fulfil many of their material desires.

The main publishing event that reflected this situation was Hanako (1988). Aimed at 25 to 27-year-old OLs (Office Ladies, i.e. office workers) with money to burn, it provided information on shops, restaurants and theatres in the Tokyo area and was sold exclusively in the metropolitan area. This magazine gave rise to the so-called “Hanako-tribe”, a group of women who were in their late twenties at the height of the bubble period and were extremely consumer-oriented and interested in frequent trips abroad, brand-name products, going to expensive restaurants, music and theatre. Hanako provided advice about handling these consumer matters – how to book a hotel room abroad, how to have the “correct” conversation at the hotel reception, and also suggested which product brands to buy.

On the other hand, a second notable publishing event highlighted a completely different trend: retailers such as Daiei and Seiyu started publishing their own magazines – most notably Orange Page (1986) and Lettuce Club (1986) – and sold them through their supermarkets. They tended to be cheaper than their competitors and to focus on practical information on how to run a household, rather like the magazines which emerged after the Second World War. In actual fact, these magazines were anticipating the severe recession of the next two decades: with the burst of the financial bubble in the early 1990s, there was a shift in consumer trends away from conspicuous consumption toward the pursuit of a more subdued and “authentic” lifestyle. Many women’s magazines adapted to the new circumstances by featuring stories on how to better manage their income. With, for instance, carried an article entitled “I am stingy!” featuring reports from readers who explained how they saved money.

During the so-called Lost Decade, more and more women decided to postpone marriage to pursue a career or free themselves from family responsibilities, and women’s magazines reflected how they coped with being single in a society that still prized the figure of women as wives and mothers. However, many magazines had a somewhat ambiguous approach to the subject, often playing on their young readers’ confusion and anxieties by presenting competing values: on the one hand, they explicitly rejected what one might call “typical Japanese values”: longstanding tradition was replaced by an endless series of fads and novelties often coming from abroad, which indulged women’s longing to be independent and join the global cultural elite; on the other hand, they reminded them that being independent was considered selfish by the moral majority; a woman might have fun for a few years, but she was expected to become a mature, modest and nurturing wife and mother sooner or later.

Another interesting characteristic of women’s magazines is the language they use. While written style in many Japanese periodicals can be quite formal, women’s magazines often bluntly lay down detailed instructions about which clothes to wear or which make-up to use. In other words, Japanese magazines know what is right for their readers and do not mince their words in order to let them know. The overall effect is both authoritarian and intimate; it can be seen as patronising and condescending. Yet the success of the magazines over the years suggests that their readers do not mind such language. According to certain scholars who have analysed this writing style, the readers of women’s magazines consider them to be sources of authority able to teach them what to do and how to do it. It’s been noted that they mimic the language of Japanese schools by encouraging imitation and repetition, which are important elements in learning. The underlying message is that women – particularly those in their 20s – are highly insecure and need advice. After spending six years in junior and senior high school, where they have to wear uniforms and follow strict rules concerning hairstyles and accessories, they suddenly find themselves free to choose how they want to look, but this freedom, though exciting, is also paralysing. So they look for advice, and find it in magazines.

Interestingly, a growing number of publications targeting college students, which first appeared in the late 1970s, often advised their readers to dress conservatively, as if it were imperative that after a long period being treated as children, they must suddenly grow up and prepare to become adults. These magazines even went as far as creating sister publications for when their readers reached the next stage in their lives: JJ (1975) and CanCam (1981) respectively launched Classy (1984) and AneCan (2007) for young women in their mid to late 20s. As usual, the interesting thing to note is the way the publishing and business worlds work together when a new title appears. For example, when AneCan was launched, the Isetan department store and several clothing companies collaborated with the magazine to create completely new brands. It was reported that when AneCan first appeared in bookshops, the “AneCan Style” brands sold 30-million-yen worth of clothing in just four days.

Magazines like CanCam even contributed to the success of celebrity models who have gone on to pursue careers in music and acting. EBIHARA Yuri, for instance, was an exclusive model for CanCam between the age of 24 and 28, then graduated to AneCam for the next eight years before signing a contract with Domani, a magazine for married and working women in their 30s.

The 1990s saw an explosion in teens’ magazines as Kogyaru (high school students) became Japan’s new big spenders and trendsetters. Long-time favourites Seventeen (1967) and Popteen (1980) were joined by high-selling titles like Nicola (1997), which pandered to girls’ every desire. It was in this period that kawaii (cuteness), the first truly Japanese postwar style, conquered the world. But kawaii wasn’t the only thing around as street fashion and gyaru culture continued to dominate young fashion. Gyaru culture, in particular, was a phenomenon based on rebellion against conformism in Japanese society, including against the Asian beauty standards of pale skin and dark hair. Its popularity peaked in the 1990s and early 2000s, with thousands of deeply tanned and blonde-haired teenagers invading the streets of Shibuya and other trendy districts, and had its own best-selling magazines including Egg (1995-2014, now only online), I Love Mama (2008-14) for gyaru with children, and Koakuma Ageha (2005), targeting women working at hostess clubs.

Women’s magazines have continued to grow in number even after the turn of the century. In 1988, there were 61 women’s magazines with a circulation of over 10,000. In 1992, there were at least 80. In 2020, the Japanese Magazine Publishers Association’s online database lists 148 titles, but their real number is even higher. The market is more diversified than ever, and while new titles keep appearing, some of the veterans disappear from the newsstands. Katei Gaho and Fujin Gaho are among the exceptions, having succeeded in adapting to an ever-changing readership. The latter, for example, is one of the oldest magazines still around (it was launched in 1905), and still has a respectable circulation of 94,000.

This said, new trends in people’s reading habits, and especially competition from the internet, have greatly eroded magazine circulation. In the early 1990s, for instance, the total monthly print run of six major titles (An An, Non-No, JJ, More, 25ans and With) came to over 7.6million copies. Today, it’s only 810,000, ranging from 25ans’ 70,000 to More’s 195,000. Whatever the case, even today, women’s magazines offer a unique window on what it means to be a woman in Japan: their tastes in food, leisure and sex; their emotional problems, worries and ambitions; how to take care of their bodies; and how to look for a partner.

G. S.

▶︎TO LEARN MORE

Women, Media and Consumption in Japan,

edited by Lise Skov & Brian Moeran, University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.

Japanese Women’s Magazines, TANAKA Keiko, in The Worlds of Japanese Popular Culture, edited by D.P. Martinez, Cambridge University Press,1998.