In its first issue, An An was notably able to feature a text by MISHIMA all about glamour.

Both in terms of graphic design and editorial content, An An turned the publishing world upside down.

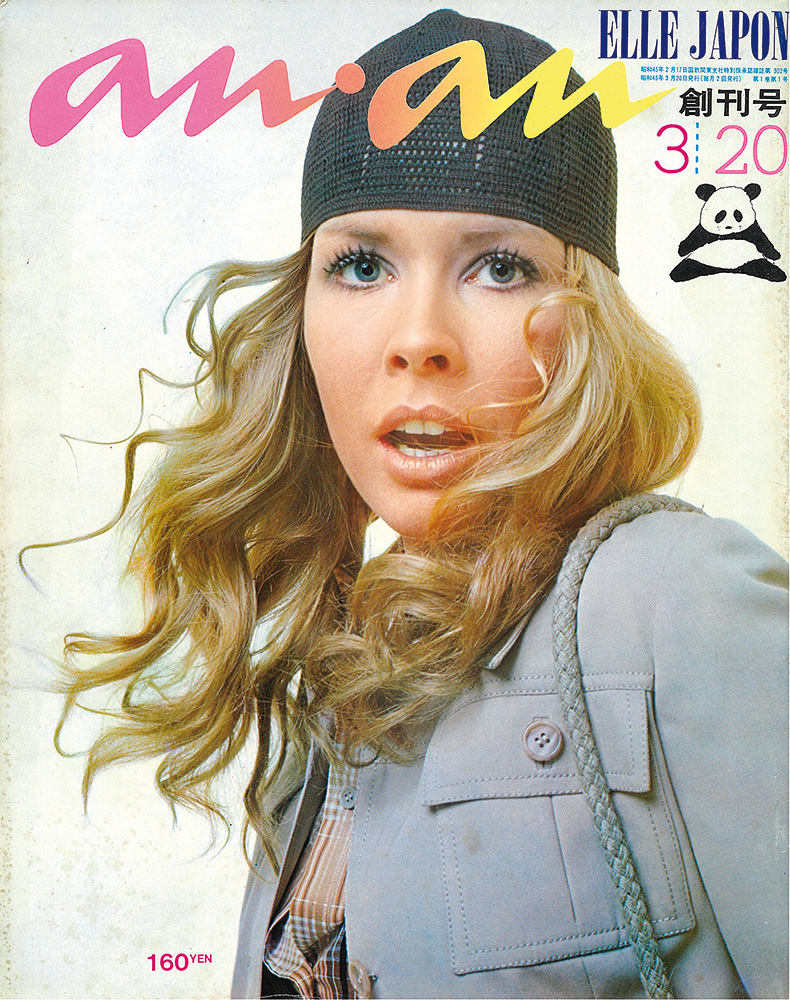

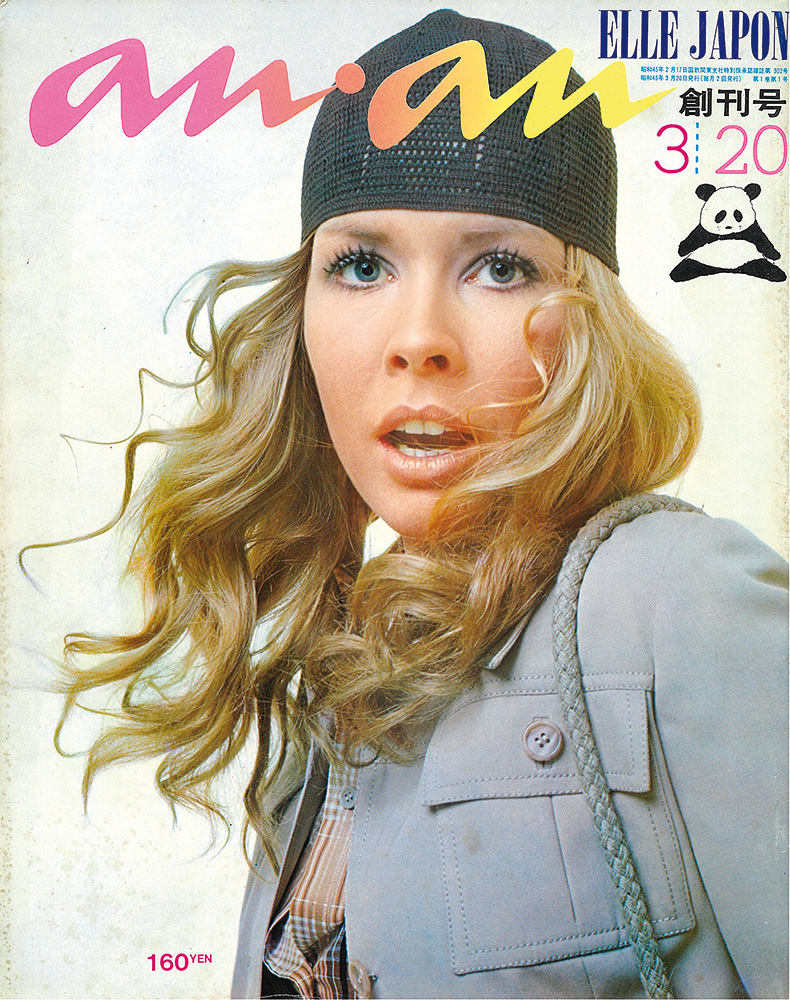

Since modern women’s magazines first appeared in Japan at the beginning of the 20thcentury, they have gone through many changes and permutations, but few editorial events can probably match An An’s sensational debut in March 1970. Its cover sported a cute panda – the magazine’s mascot – and a glamorous foreign model, Marita, the then Miss Christian Dior, whose surprised expression probably matched the look on the face of the people who first discovered the magazine on the newsstands.

With the slogan “Let’s be more fashionable”, its stunning look and exciting new content, An An was a breath of fresh air, and the Japanese publishing world was changed forever.

2,191 issues later, the magazine celebrated its 50th anniversary with an exhibition in Kyoto, and Zoom Japan had a chance to talk to curator SATO Masako about the event’s significance. SATO owns Contact, an agency that specialises in exhibition planning and production, with a focus on photography.

“The event was unfortunately cut short by COVID-19,” SATO says, “but it was nevertheless a chance to recall An An’s extraordinary run. Fifty years is a very long time for a magazine. Many publications don’t last that long, but An An’s continued success is proof that Japanese readers still find it relevant.”

When SATO was asked to organise the exhibition, she knew that it would be impossible to cover the magazine’s whole history, so she focused on its beginnings. “I was particularly interested in legendary art director HORIUCHI Seiichi, whose work I’ve always admired,” she says. “In the 1960s, when he was in his early 30s, he had worked for popular men’s magazine Heibon Punch. When publisher Heibon Shuppan (currently called Magazine House) decided to launch a women’s magazine, he joined the project and was part of An An’s creative group from the start. He was even awarded the ADC Prize in 1971 for his work for the magazine, and later went on to work for similar titles by the same publisher such as Popeye, Brutus and Olive.”

After a test run of four issues in the late 1960s (called Heibon Punch Women’s Edition), An An first appeared in March 1970 as a tie-in with the popular French magazine Elle. At a time when Japanese designers still had to make their mark on the world stage, and local fans were in awe of the fashion coming from Paris and London, this collaboration was a huge editorial coup. The first issue even included a message from the French Ambassador in Japan. With its large size, bold design and engaging stories, An An stood out among the competition and quickly became the prototype of a new kind of women’s photo magazine in Japan.

“Even today, many people in the publishing world consider An An a groundbreaking magazine,” SATO says. “Many veteran photographers and illustrators have worked for it (Marita’s photo on the first cover, for example, was taken by TACHIKI Yoshihiro) and the magazine’s fashion pages were edited by the likes of KANEKO Isao and HARA Yumiko. Like KANEKO, HARA is now a famous designer, but she was first hired as a French translator. Then, from 1972, she began to work as a stylist – the first time that such a figure had been added to the staff of a women’s magazine’s. This is just to give you an example of the kind of talented people the magazine attracted. Their original studio in Roppongi was a hotbed of creativity, and HORIUCHI Seiichi supervised everything. Then, of course, there was the writing. Many famous literary personalities such as MISHIMA Yukio and SHIBUSAWA Tatsuhiko wrote for An An. That’s definitely not the kind of people who contribute to women’s magazines now.”

An An’s novelty and revolutionary content can be best appreciated when compared to its competition. “Up to the mid-60s, many fashion magazines actually featured paper dressmaking patterns,” SATO says. “They were a throwback to a time, in the first postwar period, when boutiques were still rare and most women didn’t have the money to buy fancy clothes anyway, so they made their own dresses. Dressmaking was also a relatively easy point of entrance into the labour market, so many young women worked as seamstresses. You could say that earlier fashion magazines were closer to handicrafts than haute couture.”

The economic boom and the 1964 Olympic Games changed many things in Japanese society. People began to see life as something more than work and sacrifice. They began to seek fun and leisure as never before, and fashion was part of people’s new outlook on life. “The launch of An An must be seen as a result of this sea of change in popular attitudes,” SATO says. “It was the first Japanese fashion magazine that went beyond introducing pretty clothes. The philosophy behind An An, as stated in its first issue, was that fashion wasn’t only about choosing and wearing beautiful clothes, it encompassed music, dance, cinema, literature and the arts, what you eat and how you eat it. In this sense, it was the first Japanese publication to be comparable to the great international magazines, both in look and content. They must have spent a lot of money making it. For example, they often sent photographers and models to Europe and America at a time when foreign travel was still extremely expensive and the exchange rate was fixed at 360 yen to the US dollar. An An was an open window onto an exotic and glamorous world that few people could afford to experience in person.”

Conceived as a sister magazine to Elle magazine, in the beginning An An was made up in equal parts of original content and material sent from France. “At the time, the magazine enjoyed a degree of freedom that would be just unthinkable today,” SATO says. “Now, magazine editors have to deal with limited financial resources, pressure from advertisers and other issues, which end up affecting what can be actually done. All these things did not really exist in the early 1970s, or at least they had less impact on the magazine’s final output. An An’s editorial office’s dealings with Elle were also extremely casual. They went as far as cropping the photographs they got from France and making other changes without consulting their parent office or seeking permission.

“I’d say that HORIUCHI played a big part not only in the way the magazine looked but even in its approach to creating content and its somewhat brash attitude, and the readers felt and enjoyed the kind of vibrant energy that emanated from its pages. Without being an outright feminist publication, it retained some of the libertarian ideals of the 1960s when the Japanese student movement had joined other countries in street demonstrations and the fight for civil rights.”

An An’s gorgeous appearance is even more remarkable when we consider the tools with which publications were produced in those years. “It was still a period when magazines didn’t have all the digital tools that make editing easier nowadays,” SATO says. “They were working with film and analogue, mechanical processes, and the margin for error was very small. If they made a mistake they had to start all over again. It was the kind of work only professionals could do.”

According to HARA Yumi-ko, they would get the images from France – not digital pictures, like we do today, but original copies – and HORIUCHI would work on the layout. And once completed, they rarely returned the photos to Elle. Apparently, dozens of pictures by famous photographers like Helmut Newton have got lost somewhere. I tried to locate some of them for the exhibition, but couldn’t find any.” 1970 is considered the beginning of the Golden Age of magazines in Japan, with many titles averaging a circulation of hundreds of thousands of copies every month. An An was among them, but according to SATO, the magazine did not fare so well at first. “It was well ahead of its time,” she says. “It was a trailblazer. It pioneered things that many later titles copied and adopted, but, at the time, it was considered too avantgarde for the average reader. So after a couple of years, it went through a complete renewal to smooth down its rough edges and make it more appealing to its target audience.”

With its focus on fashion, beauty, food and travel, the magazine’s popularity and influence on young Japanese women continued to grow throughout the 1970s and the early ’80s until, in 1982, it ended its collaboration with Elle and became independent. According to the Comprehensive Catalogue of Magazines and Newspapers 1984, 88% of its readership was aged between 16 and 25, with 43% in the 16-20 bracket, and 45% between 21 and 25. Some 85% of these readers were single. With its aim of targeting young readers who “want to behave like more mature women”, the magazine kept attracting advertisers, and by 1986 more than 85% of its content was devoted to advertising and editorial tie-ins, while its circulation climbed to 650,000. Its main competition was Non-no, a magazine that first appeared in 1971. Together they gave rise to a fashion and lifestyle movement that became known as the “An-Non tribe.”

“When I was in my early 20s, I used to read many magazines,” SATO says. “Besides, in college I majored in journalism so I had a special interest in the medium. I remember that in those years – the early 1980s – women’s magazines like An An and Marie Claire, whose Japanese edition was launched in 1982, were well-crafted products where one could appreciate the quality of the page layout and each high-quality image. They might have featured clothes I would never wear, but just turning their pages was a joy to see, and they offered tips in a casual, natural way. An An stimulated your imagination and made you think, it didn’t just spoon-feed you information. By the time I turned 30, though, many monthlies had turned into simple catalogues devoid of style, so I lost interest in them. I also don’t like the patronising way in which they now tell you what to wear and how. They say, if you want to look good, follow our instructions to the letter. They don’t leave the reader any freedom of thought.” Apart from influencing the way young Japanese looked, An An and Non-no have also been credited with an increase in domestic and overseas travel among women. Around 1975, they both started carrying detailed maps not only of popular tourist places in Japan such as Kyoto and Karuizawa but also of foreign cities such as London, Paris and New York. Whatever their actual influence on tourist trends, the timing coincided with a rapid increase in the number of Japanese going overseas, many of whom were women. According to a 1993 report by Nikon Kenkyukai, in 1970, the number of people travelling abroad was only 0.7 million; in 1975, it had risen to nearly 2.5million, and by 1990 and 1991, there were more than 10million a year.

Originally coming out twice a month, An An became a weekly in the 1980s. The DC fashion brand became incredibly popular, and the girls who worked at its outlets became the magazine’s “house mannequins”. On the female appearance front, towards the end of the decade, the magazine decided that it was time for Japanese women to cut their hair short, and featured popular singer and actress KOIZUMI Kyoko with a brand-new hairstyle. For three years KOIZUMI had let her hair grow, but An An made her cut it off for its trend-setting cover.

Content-wise, the magazine embraced the bubble years of bold consumption and pursued the new image of a stronger, liberated Japanese woman. Particularly controversial was a special feature entitled “Become more beautiful through good sex”, in which the magazine clarified everything its readers wanted to know about sex but were afraid to ask. The “sex special” went on to become a regular feature, which appears every summer.

The recession of the 1990s put an end to the party atmosphere that had prevailed during the bubble years, and An An was ready to advise its readers on the best way to manage their hardearned money. A series of articles on “money studies” featured such topics as “How 10,000 yen can be spent!” and “Only 10,000 yen for all this”, in which the editorial staff showed that people could still have fun even during that difficult period in the country’s economic life.

For many people, the early Heisei era was a time of confusion and anxiety, and An An offered its two pennies’ worth of wisdom with specials on astrology (the popular “Love and destiny” still comes out twice a year) and “Love counselling” by such “experts” as AKIMOTO Yasushi (AKB48’s creator), manga artist SAIMONFumi, and long-time columnist HAYASHI Mariko. Among the readers’ favourites is also the annual “Most loved man ranking” survey, which in the 1990s was dominated by boy band SMAP member and “king of TV ratings” KIMURA Takuya. The Japanese women’s heartthrob was so popular that he even graced the cover of the magazine’s 30th-anniversary issue.

Fast forward 20 years, and the 50th-anniversary issue featured a new generation of idols: the group King & Prince. Like KIMURA in 2000, King & Prince’s members wore panda costumes. So we asked SATO about An An’s obsession with this animal. “An An is the name of an actual panda,” she says. “There are several theories surrounding the name of the magazine. Among them, there’s the story of famous TV personality KUROYANAGI Tetsuko who saw a panda called An An when she visited London Zoo. This episode must have appealed to the Japanese public because Japanese zoos didn’t have any pandas at the time. A little later, the idea to launch a female version of Heibon Punch was considered. The new magazine still lacked a name, and the four issues of the pilot edition included a postcard for readers to send in their suggestions. Eventually, they chose an idea from a high school girl from Akita Prefecture who proposed An An as the magazine’s name.”

In the last 50 years, the magazine market has shrunk considerably, but An An still commands a respectable circulation of 152,000. Like 50 years ago, the magazine’s keywords are kawaii (cute), oishii (delicious) and oshare (stylish, fashionable), where the last term refers to both women’s fashion and the guys who are regularly portrayed on its cover. “Today’s An An cannot really be compared to the original publication,” SATO says. “Now, it seems its readers are mainly interested in boy idols, and the magazine has had to adapt to their tastes, which is not necessarily a bad thing, it’s just the way things go in the publishing world. The remarkable thing, in my opinion, is that magazine covers still retain the power to attract readers and sell copies. I mean, idol-related stories can be found everywhere on the internet, but fans will buy a magazine just because it sports a photo of their favourite idol on the cover.

Now, most publications are always trying to catch up with ever-changing fads. An An is one of the few exceptions that still has the power to be a trend-setter.”

JEAN DEROME