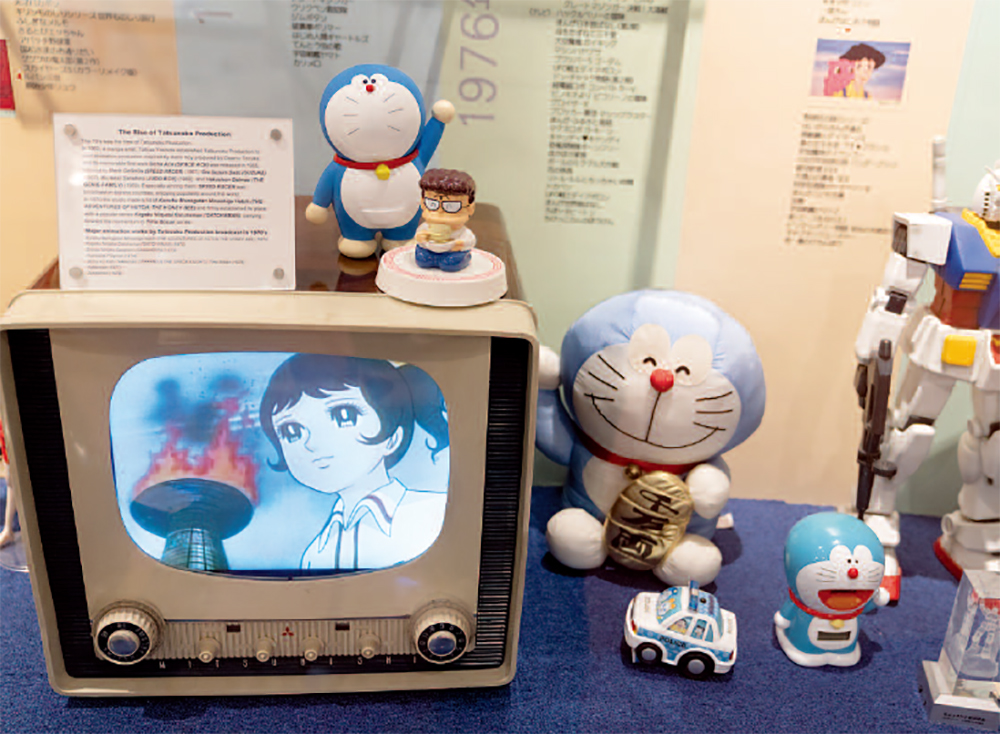

In Tokyo’s Suginami Animation Museum, you’ll find souvenirs of the Olympic Games with the series Atakku No. 1, adapted for television at the end of the 1960s.

There are countless numbers of manga series devoted to sport. Zoom Japan has done some investigating.

Japanese comics are famous, among other things, for covering the most disparate topics under the sun. Besides the usual array – adventure, romance, superheroes, SF, etc., – a typical Japanese bookshop carries stories about office life, cooking (see Zoom Japan #03, July 2012), old age (see Zoom Japan #73, July 2019), wine (see Zoom Japan #76, November 2019), religion (Jesus and Buddha as lazy roommates), and even weirder subjects like a woman who turns into a fridge. But few genres are as popular and have had as much influence on society as sports manga, whose importance in Japanese culture was reaffirmed in Tokyo last summer with a great exhibition, Sports x Manga, curated by Stephane Beaujean, the Artistic Director of Angoulême’s International Comics Festival.

Sports manga’s real breakthrough came in 1966, when Kyojin no Hoshi [Star of the Giants] came out in Weekly Shonen Magazine. It was an instant hit, and in 1968 it was adapted as the first sports anime to be broadcast on Japanese TV.

Two years before, the Tokyo Olympics had signalled Japan’s rise from the ashes and its return to the world stage. The country regained its pride after an impressive performance by its athletes (29 total medals including 16 golds). Japan did particularly well in judo and volleyball, two disciplines that made their Olympic debut in Tokyo. In judo, Japan won three of the four classes. The men’s volleyball team earned a bronze medal with a 7-2 score in the round-robin tournament, but was outdone by their female counterparts – the famed “Witches of the Orient” – who became Olympic champions with a perfect 5-0 score. Their triumph over the Soviet Union on the final evening of the Games was later voted by the Asashi newspaper as the fifth greatest sporting achievement of the 20th century.

Naturally enough, Japan’s success in judo and volleyball was followed by a number of manga devoted to these sports, among them Judo Icchokusen (1967) and, in particular, the groundbreaking Atakku No.1 [Attack No. 1](1968), which was responsible for the explosion in the shojo manga genre.

The “witches” of the volleyball team were coached by DAImATSU “the Ogre” Hirobumi, a former military man who was infamous for his brutal training methods that came to be known as suparuta (homicidal training). every day the girls worked from 8:00 to 16:00 at their office then went to the gym at 16:30 to train almost nonstop until midnight. Probably the hardest part of their training was the so-called kaiten reshiibu (receive and rotate), a dive-and-roll move designed as a defence against the spike (an attacking move), which the girls were forced to do over and over again until they could no longer stand up. According to coach DAImATSU, it was thanks to his brutal methods that Japan won both the World Championship in 1962 and the Olympic gold medal and, once, achieved a streak of 258 victories in a row. To this day, Japanese sports are characterised by this almost sadistic (which the coaches prefer to call “character-building”) approach to training, and the manga that first appeared in the 1960s and ‘70s highlighted this heroic aspect of sporting life. That’s why the genre was labelled supokon or “sport konjo”, konjo meaning “guts”.

HOSHI Hyuma, the protagonist of Kyojin no Hoshi, is a typical example of a supokon hero. A promising young pitcher whose dream is to emulate his father and make it in the professional league, he goes through one gruelling training session after another. One of the story’s highlights takes place at the annual high school tournament (one of Japan’s most important sporting events) at Koshien Stadium, where HOSHI meets his rival HANAGATA Mitsuru in the final.

HOSHI struggles with his pitching because of a broken nail until the last at-bat comes and he has to summon all his strength and skills to throw one last blood-stained ball. The rivalry between HOSHI and HANAGATA then continues when they join the Tokyo Giants and Osaka’s Hanshin Tigers respectively.

Even in real life these were the country’s most popular professional teams. The Giants, in particular, are often compared to the New york yankees because of their dominance of the top league. When Kyojin no Hoshi came out in 1966, the team was on its way to winning the second of their record nine consecutive Japan Series championships (1965-1973).

One year later, baseball, judo and volleyball were joined by a smash-hit boxing manga: Ashita no Joe [Tomorrow’s Joe]. This comic was authored by KAJIWARA Ikki, the same prolific writer who, working with different artists, was creating Kyojin no Hoshi and Judo Icchokusen. A quintessential supokon manga, this story of a troubled young man who runs away from an orphanage and spends time in jail before becoming a famous boxer is full of blood, sweat and tears, and includes surreally absurd episodes such as one of Joe’s rivals (who is actually three weight classes above him) undergoing dehydration and a suicidal weight loss programme just to be able to challenge him in the ring (obviously, the poor fellow dies at the end of the match). Another strong contender, Carlos Rivera, is left with permanent brain damage after being knocked out by World Champion Jose mendoza.

The final match between Joe and mendoza is an incredibly brutal fight, both men knocking each other down more than once no matter how badly injured they are. eventually, mendoza scraped through to win on points, his hair having turned white due to the stress. As for Joe, he is dead from his injuries. His trainer finds him sitting in the corner of the ring, a smile on his face.

Joe became an instant cultural icon among both young workers and students as the manga came to represent the struggles of the lower classes in the 1960s as well as the sacrifices imposed on Japanese society during the postwar reconstruction. The story and its characters became so popular that hundreds of fans dressed in black to mourn the death of RIKIISHI, one of Joe’s rivals, while Kodansha, the manga’s publisher, was flooded with consolation letters and funeral flowers. Poet and director TeRAyAmA Shuji wrote an essay, Dare ga Rikiishi o Koroshita ka [Who Killed Rikiishi ?], in which he pointed out that Joe – who actually lost that match – was planning to use his prize money to clean up the slums and build hospitals, nursing homes and apartments. eventually, he organised a funeral at Kodansha headquarters that was led by a real Buddhist priest.

The 1970s saw other disciplines successfully join the ranks of manga about sport, among them sumo wrestling (the long-running Notari Matsutaro [Carefree matsutaro] was published between 1973-93, then again from 1995-98) and golf (Puro Gorufua Saru [Pro Golfer monkey]). Car racing manga Sakitto no Okami [The Circuit Wolf] was responsible for sparking a supercar boom throughout the country, while best-selling tennis manga Esu o Nerae! [Aim for the Ace!] is still considered to be one of the most influential sports manga of all time. Despite being a shojo manga devoted to an “exotic” and fashionable european sport, even Esu o Nerae! displays all the characteristics of a typical supokon story including sacrificing romance for sporting success and such unhealthy practices as continuing to play though seriously injured.

However, even in the 1970s, baseball continued to dominate the sports manga market with a long list of new entries. Arguably the most original title was Asutoro Kyudan [Team Astro], the outlandish story of nine superhuman players (born with a ball-shaped mark on their arms) who get together with the aim of becoming the world’s strongest team. The manga is full of inconsistencies and mistakes in baseball rules as well as improbable moves such as the “Sky Love” pitch and “Comet Giacobini” hitting technique, but it’s unrivalled in the way it depicts the passion for the sport. Indeed, there are so many plot twists and dramatic scenes throughout every agonizingly long game that only three matches are featured throughout the story’s 183 episodes.

This manga is also notable for being an early example of Weekly Shonen Jump magazine’s new approach to manga-making, based on the readers’ feedback on the postcards enclosed in every issue. While, even in later decades, sports manga continued to thrive, their characteristics began to change in the 1980s when the rough and gritty supokon were replaced by what anime historian TSUGATA Nobuyuki calls “clean” stories. According to TSUGATA, supokon appeared during a period when a lot of people in Japan were fighting to improve their lives. These early comics showed that life, far from the social harmony promoted by the government, was a battle between the strong and the weak, the rich and the poor, and victory was the only way to personal growth and a rise in social status.

However, by the early 1980s, Japan had become a mature economic power and was threatening America’s position as the world’s number one. The average income had grown considerably, and more and more people could afford to buy all the newest electronic gadgets, and even travel abroad. In this more relaxed and increasingly hedonistic atmosphere, many sports manga started focusing on more universal themes and the characters’ daily lives including their romantic adventures. The biggest hit of the decade, Tacchi [Touch], is a typical example of this trend as sport – highschool baseball in this case – is just one of the passions our heroes – twin brothers Tatsuya and Kazuya – share, the other one being Minami, the girl next door. Author ADACHI Mitsuru had already penned a classic supokon story called Nain [Nine] in 1978-79, but when Tacchi debuted in 1981, its fresh mix of sport and romance became an instant hit among teenagers. It went on to sell more than 100million copies, and even its anime adaptation is one of the highest-rated anime TV series ever.

At times it seems as if ADACHI wants to distance himself from the old style. For example, while Tacchi is about teams battling to qualify for the high-school finals at Koshien Stadium, the story ends without actually showing the finals. Also, after Tatsuya’s team wins the regional final and the right to go to Koshien, his rival asks for a rematch, but he just shrugs it off saying that he has had enough.

The other important development in the 1980s was that football came out of nowhere to become one of the most popular sports featured in Japanese comics. manga’s first foray into football had been Akakichi no Eleven [Red-Blooded eleven], a quintessential supokon story (please note the dramatic title) by the hyper-productive KAJIWARA Ikki, featuring such over-the-top moves as the “submarine shot” and the “boomerang shot”. At the time, football was still a minor sport in Japan, but the national team had won a surprise bronze medal at the mexico City Olympics (1968).

The real game changer, though, was TAKAHASHI yoichi’s Kyaputen Tsubasa [Captain Tsubasa], which grabbed the fans’ attention and spread football fever around Japan. In contrast to Tacchi and other ‘80s manga, Kyaputen Tsubasa is still very much a product of the ‘70s. In fact, though the story was turned into a series from 1981, TAKAHASHI spent two or three years working on it and trying to get it published. Concerning content, there is the usual heavy dose of guts and sacrifice together with a strong sense of honour, friendship and camaraderie. Indeed, according to TAKAHASHI, he chose football over the more popular baseball because, according to him, the role of teamwork in football is more important. Time and again, the young players are ready to risk their bodies and future careers in order to play an important match and help their team win. Between exhausting training sessions, frequent injuries and life-threatening episodes (one boy chooses to play though he has a dangerous heart condition) football as portrayed in TAKAHASHI’s stories looks and feels more like a never-ending war – a matter of life and death – than a sport. One of the principal matches depicted in the story, for instance, lasts some 20 episodes. The decade ended with URASAWA Naoki’s Yawara!, a story that rekindled the Japanese love for judo.

The 1990s brought about further diversification in the sports manga genre, and a handful of new hits. Hono no Tokyuji: Dodge Danpei [The Fireball Kid: Dodge Danpei], for example, helped make dodgeball popuar among school children, while the title Kyotei Shojo [Speed Boat Racing Girl] tells you everything you need to know about the story. Kaze no Daichi [Windy Plains] mixes golf and romance and Ganba! Fly High is a rare example of a manga in which the story’s author (mORISUe Shinji) is a former gymnast and Olympic champion. At the same time, MITSUDA Takuya’s Major re-established baseball’s premier position among sports manga by following Kyaputen Tsubasa’s example by portraying the protagonist’s development and tribulations from kindergarten through to becoming a professional player in the American major Leagues.

But the greatest hit of the decade – and one of the best-loved sports manga ever – was about a teenage delinquent who plays a minor sport to impress girls. In the 1990s, basketball might have been a favourite with fans in europe and America, but nobody seemed to care about it in Japan. As a consequence, it was considered a taboo subject in the comic industry, and no editor wanted to touch it. Then author INOUeTakehiko convinced publisher Shueisha to make a manga about basketball, the sport he used to play in high school. The readers’ response was astonishing – Slam Dunk (Suramu Danku, ed. Viz media) became such a smash hit that it sold more than 120million copies in Japan alone, single-handedly turning basketball into a cool sport.

Since then, INOUe has become a sort of basketball ambassador, creating two more titles in the ‘90s, Buza Bita [Buzzer Beater] and Real (Riaru, ed.Viz media), the latter about wheelchair basketball. As for Slam Dunk, in 2006 it was voted the number-one manga of all time in a poll of 79,000 comic fans, and in a 2009 poll about people’s favourite works of art, it took first place in the manga category.

But what about sumo? After all, this is what many people consider to be Japan’s national sport. Admittedly, the big fat guys have never been one of the hottest items in manga, but the new century has seen the birth of a rather successful franchise thanks to SATO Takahiro, the author of Bachi Bachi. The story follows another bad boy, SAMEJIMA Koitaro, the only son of a disgraced sumo wrestler star, while he fights his way into a team and then through the ranks of the professional sumo world. It was turned into a series between 2009 and 2012 and was popular enough to be followed by two sequels, Bachi Bachi BURST (2012-14) and Koitaro, the Last 15 Days (2014-18).

JEAN DEROME