The iron bridge (rikkyo) spanning the tracks of the Chuo Line, which Dazai Osamu liked to frequent, is still a favourite spot for local inhabitants.

Dazai Osamu is one of the most celebrated writers in the country, whose life and death are closely connected to the famous railway.

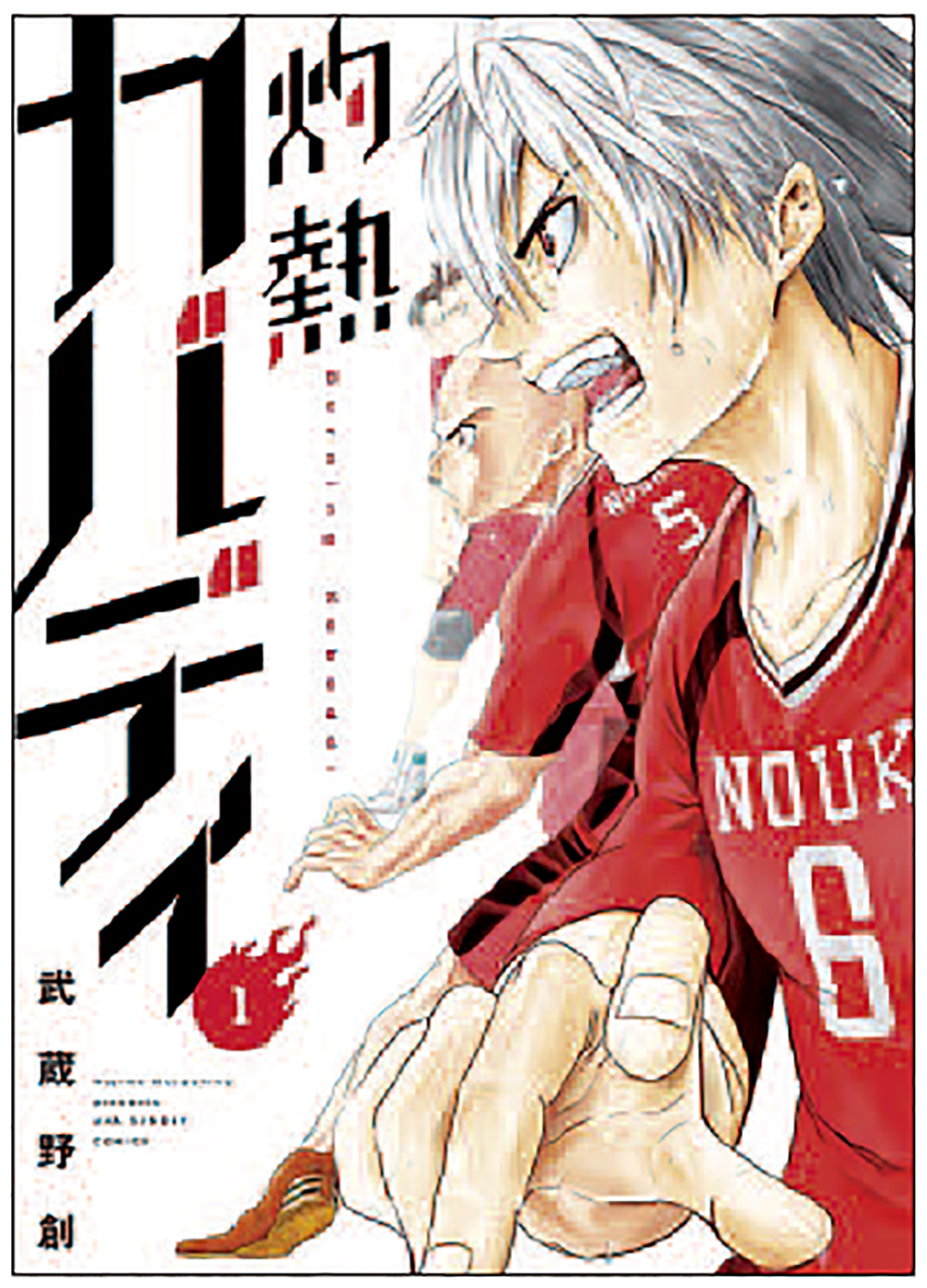

For many years the Chuo Line – and the districts between Asagaya and Mitaka rail- way stations in particular – has been a magnet for many writers and intellectuals, but few people have charmed and fascinated their readers like DAZAI Osamu, the author of such masterpieces as The Setting Sun (1947) and No Longer Human (1948) and who lived in the area from 1936 until he committed suicide in 1948. In Japan, his existential tales of anti-heroes who are at odds with society have attracted a loyal following among high-school and university students. DAZAI’s popularity among the younger generations is such that even a manga character was named after him. In Bungo Stray Dogs (lit. Literary Stray Dogs), DAZAI is a senior member of a detective agency who has a supernatural power called No Longer Human and, like the real-life author, is always trying to kill himself. (Other characters, by the way, have such names as TANIZAKI Jun’ichiro, MIYAzAWA Kenji, NAT- SuME Soseki, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Francis Scott Fitzgerald… That’s what you can expect from a manga author called Asagiri Kafka.)

The then 27-year-old DAZAI first moved to Suginami with his wife in March 1936 when, with author IBuSE Masuji’s help, he found a house in Amanuma, between Asagaya and Ogikubo stations. But one year later his friend KODATE zenshiro confessed while drunk that he had slept with his wife. The sudden marital breakdown precipitated another existential crisis for the troubled writer, and the couple divorced a few months later after trying unsuccessfully to take their lives – DAZAI’s fourth suicide attempt.

However, DAZAI didn’t remain single for long because in 1938 he married Ishihara Michiko, a 26-year-old teacher in a high school for girls. In September 1939, the newlyweds moved to Shimo-Renjaku, in today’s Mitaka. One of their neighbours was literary critic KAMEI Katsuichiro, with whom DAZAI became friends. He even joined the Asagaya-kai, a group of novelists, poets and playwrights who met to play shogi (Japanese chess), drink, and engage in heated literary discussions.

Though a seemingly endless stream of acquaintances and fans went on pilgrimage to Osamu’s house, these were years of intense work. Except for a period toward the end of the Pacific War when the DAZAIs evacuated to Michiko’s home- town in Yamanashi Prefecture, Mitaka is where the author spent the last and most creatively prolific period of his life.

After the restless Tokyo years when he never seemed to find a suitable environment to live (he moved 11 times in three years), DAZAI finally felt at home in Mitaka. This was the place where his wife and children lived and where he could find temporary respite from his demons. It was also a favourite location for many of his works. During those years, DAZAI became a mentor to other aspiring writers. Among his followers was TANAKA Hidemitsu whom he first met in Mitaka in 1940. A former Olympic rower (he was a member of the Japanese team at the 1932 Los Angeles Games) and Japan Communist Party member, TANAKA belonged to the same Buraiha (Decadent School) with which DAZAI was associated. DAZAI was greatly impressed by TANAKA’s writings and tried to help his literary career. He is said to have modelled the raccoon dog that appears in Otogi-zoshi (1945) on him. However, TANAKA, like his mentor, had a troubled life and in his later years suffered from alcoholism, drug abuse and mental instability. Deeply shocked by DAZAI’s suicide, he took his own life one year later by cutting his wrists after taking an overdose of sleeping pills.

At 1.75m, DAZAI was taller than the average Japanese, and rather handsome. On the other hand, he had terribly bad teeth (at 32, his mouth was already full of false teeth), but this didn’t prevent him from attracting many female fans. One of them was OTA Shizuko, whom he first met in Mitaka in 1941. She became his lover and even bore him a daughter.

When DAZAI first moved to Suginami, Mitaka was a quiet farming area, and his house was surrounded by fields. However, the almost rural landscape rapidly changed during the war when the country’s fortunes gradually dwindled. Several factories were built to meet the growing need for weapons, and Mitaka became the target of the American raids.

In March 1945, the DAZAIs moved to his wife’s home in Yamanashi just before their house was bombed. They didn’t return to Suginami until the end of the war.

Amid the destruction and pervasive sense of loss and doom, DAZAI’s postwar life couldn’t have been better, at least on the surface, as many of his stories were published in magazines, and he became increasingly popular. In January 1947, he visited OTA Shizuko in order to borrow her diary. Working on that material, he wrote one of his best novels, The Setting Sun (1947), whose success made him a rising literary star.

The cemetery where the writer’s tomb is located still attracts many of his admirers.

His private life, though, was full of problems. After being diagnosed with tuberculosis during the war, he became an alcoholic and his health rapidly deteriorated. Also, and most worryingly, he had an increasingly complicated love life. On the one hand, he became a father for the third time (his daughter Satoko would become a famous writer under the pen name TSuSHIMA Yuko). On the other hand, OTA Shizuko, with whom he had an on-off affair, became pregnant almost at the same time. When he heard the news, DAZAI ended their relationship. Deeply hurt by his attitude, Shizuko decided to keep the child anyway, and he agreed to pay monthly child-support. Their baby was called Haruko (lit. “Osamu’s child”).

One reason for DAZAI’s coldness was that he had met another woman in the meantime. In order to avoid his many visitors and better concentrate on his writings, he had rented a room above a diner, and often spent the night drinking down- stairs. There he met YAMAzAKI Tomie, a beautician and war widow who had just moved to Mitaka and lived opposite the diner. After falling in love, he left his wife and children for good and moved into Tomie’s room where he kept writing while she nursed his rapidly deteriorating health.

On the night of 13 June 1948, after leaving his unfinished story “Goodbye” on his desk, DAZAI and YAMAzAKI walked to the nearby Tamagawa Aqueduct and drowned themselves. Their bodies were not found until the 19 June – what would have been his 39th birthday.

DAZAI’s death caused a furore around the country because of the circumstances surrounding it and the fact that Tomie was one of the many young women who had lost their husbands during the war. Nearly three years after the end of the conflict, this was still considered a big social problem in Japan. Helped by the publicity and the public’s morbid curiosity about his suicide, The Setting Sun sold 90,000 copies in a few days, while a special issue of the Shukan Asahi weekly magazine sold out in two hours.

Since his death, there have been two more “DAZAI booms” in Japan, one in the mid-50s and the second one in the second half of the ‘60s. His gloomy tales of desperate lives particularly resonated with the sense of emptiness and social entrapment felt by the thousands of students who were demon- strating and fighting the police in the streets of Tokyo and other major cities in the late ‘60s.

Mitaka has changed a great deal in the last 70 years. When DAZAI moved there in 1939 only about 15,800 people lived in what was more like a country village than a proper city. Today, though, its population has risen to 186,000. That said, a few places still remain that remind us of DAZAI’s life and Mitaka in the 1940s. For example, the overpass to the left of the station that crosses the railway and train depot is still there in all its rusted splendour. DAZAI liked to watch the sunset from that high point, and in one of his works even mentioned being mesmerized by the red burning sun that sank below the horizon. These and other memories are displayed on a small sign near the south side of the overpass.

Of course, the Tama-gawa Aqueduct still flows literally under the station and through Inokashira Park. DAZAI loved to stroll alongside the aqueduct before crossing the bridge in the park and continuing to Kichijoji Station. Nowadays, the Tama-gawa is just a narrow, shallow and harmless stream of water, but during DAZAI’s time it was deeper, with a strong current, and was considered quite dangerous. According to DAZAI, the locals called it the “people-eating river”. In Kojiki Gakusei (The Beggar Student, 1940) he featured a real-life incident from 1919 when a child fell into the Tama-gawa during a school trip and a teacher drowned while trying to rescue him.

Finally, DAZAI was buried at zenrin-ji, a Buddhist temple, almost in front of the tomb of MORI Ogai, a writer whom he greatly respected. It was here, by the way, that TANAKA Hidemitsu took his life in 1949. For most of the year, zenrin-ji is a quiet place, but every 19 June, scores of admirers gather around his tomb to celebrate “Otoki” (lit. “cherry mourning”), DAZAI’s birthday and the day his dead body was found.

At first, only his close friends and fellow writers used to meet once a year to remember the author, but in the late ‘50s they were joined by an increasing number of fans until in the ‘60s some 500 people would gather at the cemetery for the occasion.

If you feel like paying your respects, don’t forget to check out Phosphorescence, a DAZAI-themed secondhand bookshop and café just a 15-minute walk south of the cemetery.

J. D.