Tuttle Publishin

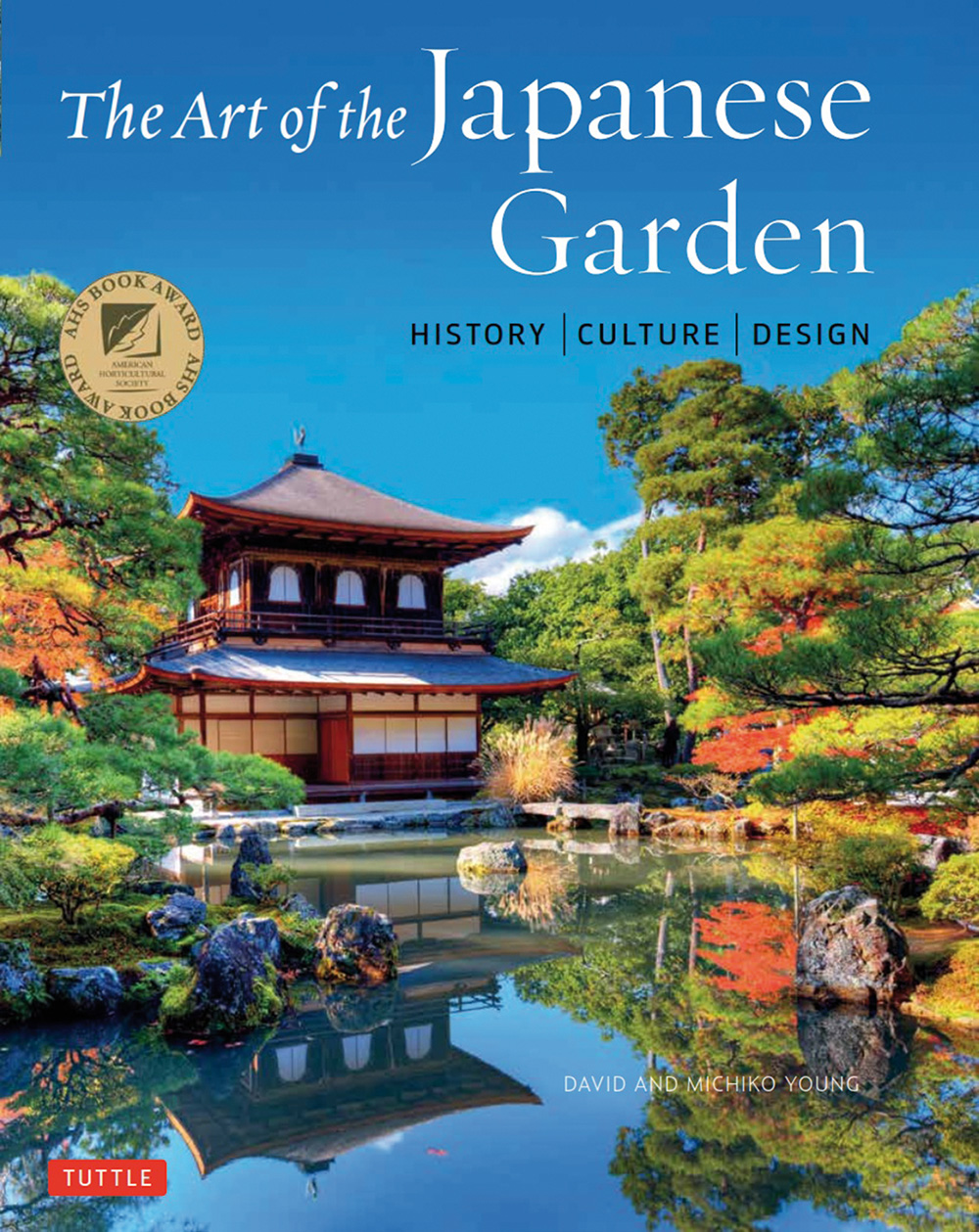

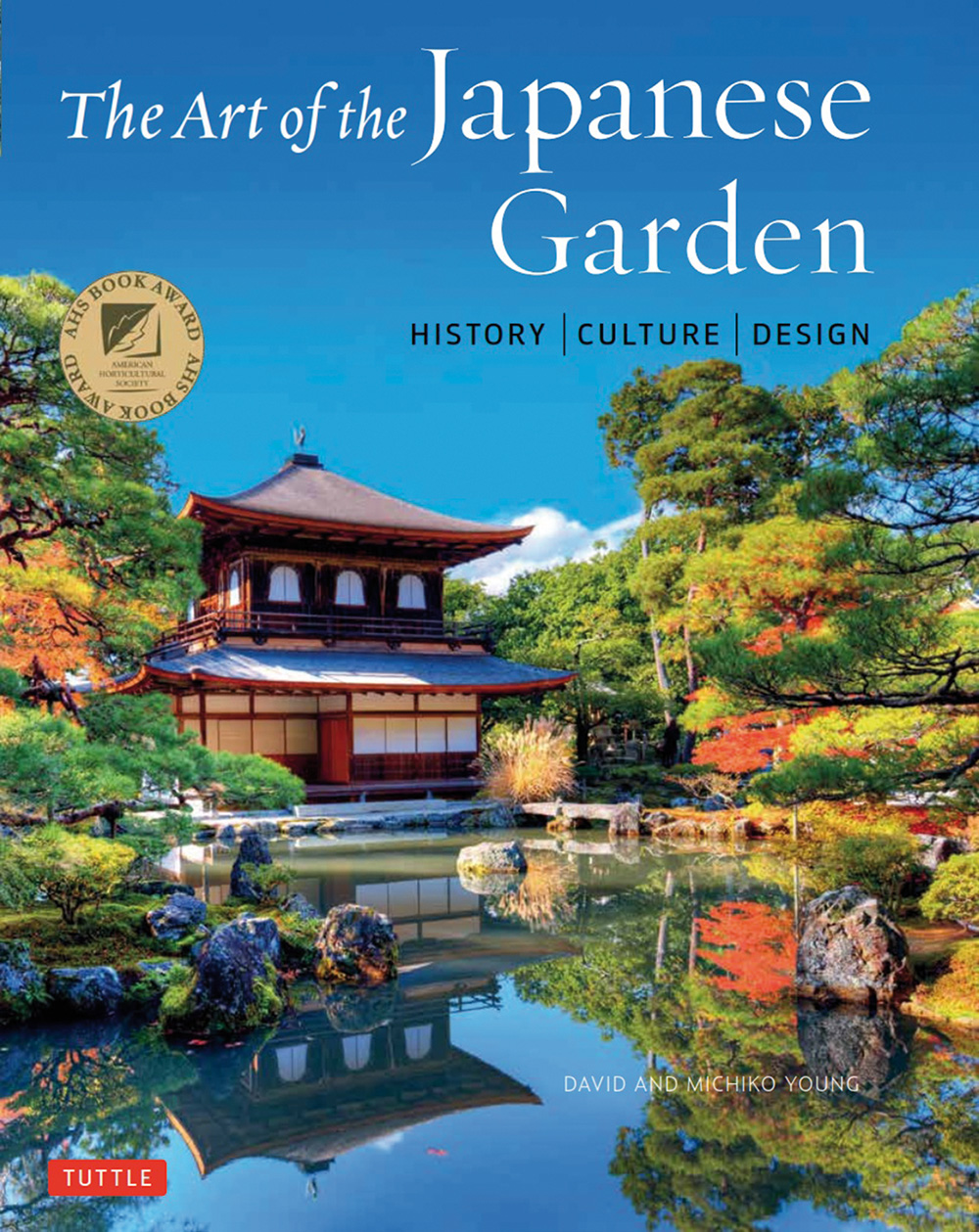

In this outstanding work, the authors take readers on an incredible journey into the heart of Japanese beauty.

Steve Jobs echoed the thoughts of many of us when he described Japanese gardens as “the most sublime thing I’ve ever seen”. If you’ve ever visited a Japanese garden, you’ll know what he means. There’s something about the arrangement of trees, shrubs, ponds and rocks, the careful placing of a stone lantern, or a graceful little red bridge, which creates an effect that is both serene and exciting. The sight of it makes you gasp involuntarily; you feel your heart leap. Then you recall that other Japanese gardens achieve the same effect without using a single flower. Nothing but rocks and gravel. Hardly a garden at all in the traditional Western sense. There are gardens you walk around, and gardens you sit and contemplate from inside a room. Pretty soon, you realise that there’s a lot more to Japanese gardens than you imagined in that first spellbound glimpse. You’re left wondering just what it is that makes them so sublime.

In The Art of the Japanese Garden, authors David and Michiko Young attempt to supply the answer by delving into the development of Japanese gardens over the centuries. They also examine the intricate interplay of elements and design principles that help create the sublime effect.Dis- covering exactly what is involved in the design of an authentic Japanese garden, the complexities that go into achieving the apparent simplicity makes for fascinating reading..

You’ll be struck by the sheer variety of styles that come under the umbrella of “Japanese Garden”. Traditionally Japanese gardens have been divided into three main kinds: natural scenery gardens, which represent nature with rocks, ponds, bushes, etc.; dry landscape gardens, which use gravel rocks and sand to suggest natural scenes; and tea ceremony gardens consisting of landscaped paths leading to the teahouse.

However, the authors forego this oversimplification, preferring to organise their investigation in terms of historical development. We therefore find sections on Heian Gardens, zen Gardens, Samurai Gardens, Tea Gardens and several more. The characteristic style and components of each period are explained in detail. Splendid colour photos of the various types of garden adorn every page, further helping the reader to understand the stylistic differences.

Daitokuji, Kyoto.

The book, which won the American Horticultural Society Book Award, begins with a brief historical overview. It also touches on the important distinction between sacred gardens – those that evoke spiritual feelings and philosophical insights – and secular ones, designed to “stimulate an aesthetic response”. With the ground thus prepared, the next thirty pages, entitled Basic Elements and Principles, look at a garden’s typical components. The most important elements are the structural ones such as rocks, trees and water, arranged to suggest mountains, waterfalls, valleys and meadows. How this miniaturisation of large-scale landscapes is achieved in a limited space never fails to intrigue. Other principles include asymmetry, where no single element dominates, and miegakure (hide and reveal), where the garden is arranged so that not everything can be seen at once. At the heart of all these principles is the fact that, while the garden is designed to look as natural as possible, it is above all a work of art. Of great importance in achieving this artistic goal are the decorative elements – stone lanterns, pagodas, koi carp, flowers, and buildings like pavilions and teahouses. Once again, the sheer variety is staggering. Stone lanterns, for example, can range from the rustic kind, made of natural stones barely modified by human hand, to intricate works of art sculpted in granite.

The role of the changing seasons is also crucial. The gardener must “bring out the intrinsic nature of a landscape scene in such a way that it is beautiful in all seasons of the year”. The bulk of the book is devoted to the section Japan’s Most Notable Gardens, in which the authors discuss the historic development of the different styles of gardens in chronological order. Here, they also consider the influence that broader cultural forces have had on the evolution of Japanese gardens.

They start with the dry gravel courtyards associated with early Shinto shrines, like Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie Prefecture, and progress up through the Heian, Edo and Meiji periods and into the modern era. They look in detail at gardens representative of each style from across Japan, exploring the cultural background and specific components that characterize each one. These examples range from the gravelled courtyard at Nara’s Horyu-ji Temple (Japan’s oldest temple) to the zen gardens at Tofuku-ji Temple’s Hojo Garden. Finally, we see a couple of modern gardens and some Japanese gardens abroad. Newcomers will find the wealth of insight and information offered by this book makes an ideal introduction to this fascinating art form. And even veteran garden-goers will find it helps them approach familiar gardens with renewed enthusiasm and knowledge.

STEVE JOHN POWELL