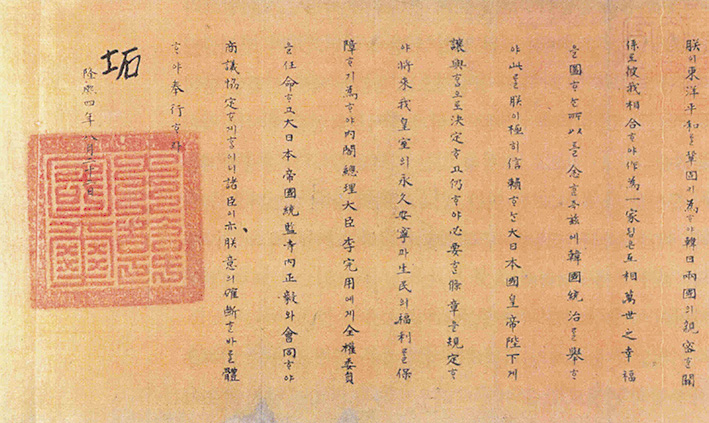

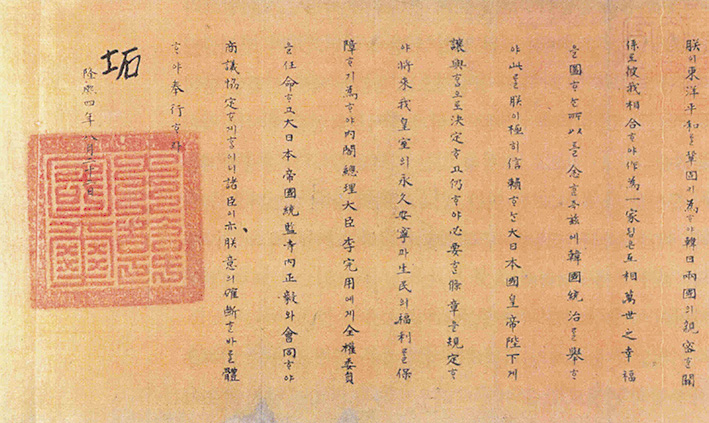

The Annexation Treaty formally placing Korea under Japanese rule was signed on 22 August 1910 by the pro-Japanese Prime Minister Yi Wan-yong and sealed by Sunjong, the last Emperor of Korea./All Rights Reserved

According to OKUZONO Hideki, the two present governments have mismanaged the situation and made it worse.

Japan and South Korea have been fighting and arguing for years about the past. However, this time they seem to have painted themselves into a corner, and it’s hard to see how they’ll be able to overcome the current disagreements and salvage their troubled but important relations. Zoom Japan talked to OKUZONO Hideki about the causes and possible consequences of the latest clash between the two countries. A former Asahi Shimbun correspondent, OKUZONO is an associate professor at the University of Shizuoka and deputy director of the university’s Centre for Korean Studies.

OKUZONO’s first experience of Korea was 30 years ago, when he studied for two years at Yonsei University in Seoul. He later taught at Dongseo University in Busan, and even now visits Korea four or five times a year to keep abreast of the latest developments.

“If you really want to know South Korea you should take the time to visit the country regularly because it’s changing so rapidly,” OKUZONO says. “Every time I go, I try to meet as many people as possible, from politicians and bureaucrats to journalists and academics. Also, there’s a big gap between generations in outlook, so I always try to talk to students as well. They’re very passionate and very committed to studying.”

When OKUZONO first lived in Seoul, soon after the 1988 Olympics, the situation was very different from now. “At the time, Japan was clearly considered a leader, a model to follow and emulate, as Korea desperately tried to catch up with its richer, more accomplished neighbour,” he says. “However, now the two countries are almost at the same level, and Koreans feel they can finally come out of Japan’s shadow and deal with it as equal. On the other hand, the Japanese government is still treating them like younger siblings who need guidance and, when necessary, to be scolded. This, of course, annoys them no end.”

The latest rift between the two countries revolves, yet again, around a wartime issue, namely the use of forced labour in Japanese factories and mines. The people who are suing the Japanese companies claim that they were forced to work in appalling conditions without pay. “Nobody denies these facts,” OKUZONO says. “The real problem is how this issue has been dealt with in the past. In 1965, the two countries signed a treaty that covered compensation claims dating back to Japan’s colonial rule of Korea. To this day, the Japanese government’s position is that all problems were settled on that occasion, and there’s no need to argue any further about them. They apologised, paid reparations, and the Korean government agreed that the 1965 treaty settled their past troubles once and for all.”

However, the Korean government now sees things differently. For example, there are a few issues that weren’t taken care of properly at that time, namely “comfort women”, the Korean victims of the atomic bombings, and all those Korean citizens who were left behind when the northern island of Sakhalin was invaded by the Soviet army, and couldn’t return to their home country. These three issues, according to South Korea, must be settled separately. Until now, the Korean government had been careful not to rock the boat because it didn’t want to disrupt its relations with Japan. Un- fortunately, last October’s ruling by the Supreme Court changed things dramatically. “I think the Korean government was not only caught by surprise but didn’t really like the Supreme Court’s ruling,” OKUZONO says.

The ruling placed the issue of wartime Korean labourers outside the scope of the 1965 agreement. The court took the position that since, throughout the negotiations, Japan refused to acknowledge the illegality of its colonial rule, the agreement does not cover compensation for illegal activities on the part of both the Japanese government and businesses. In other words, as most Japanese activities during that period are considered legally invalid, a great number of Koreans who were negatively affected by those activities now have the right to seek damages.

Japan, of course, sees things differently. According to the Japanese government, these latest developments are more to do with Korean internal affairs, and Japan shouldn’t be involved.

“Korea is now a democracy based on the separation of powers (legislative, executive and judicial), and the executive cannot interfere with decisions made by the judicial arm of the government,” Okuzono says. “Obviously, the Korean Cabinet has to accept the Supreme Court’s ruling. On the other hand, however, the separation of powers is based on a system of checks and balances. In my opinion, when a decision is made by the judicial power, for ex- ample, that threatens the country’s foreign policy, it is the executive’s duty to take care of those matters and reconcile everybody’s position. That’s exactly what the Korean government has avoided doing so far.”

Many observers and commentators – even those who in principle take the side of South Korea’s wartime-related claims – seem to think that, this time, the Korean government has gone too far as it keeps pushing the limits of what it can get from Japan. But a lot of Koreans don’t see these things in the same way. “When I talk to Koreans about this problem and explain the Japanese government’s point of view, many people reply in the same way: Japan should show more humility. After all, Japan was the aggressor during the war, and Korea was the victim, not the other way around. Why does Japan criticise us for discussing a problem they started in the first place? Why do they always have to quibble?”

Benjamin Parks for Zoom Japan

The real issue here, as OKUZONO points out, is that the two countries see things so differently they seem unable to find common ground. “For the Japanese, formal agreements are a serious thing,” he says. “Once you sign a treaty, you have to abide by it. There’s an expression in Japan: a rule is a rule, even a bad one. If you’re not satisfied with a particular law, then change it. But you cannot keep pushing the limits of what was agreed on. The Koreans, though, think differently. The most important things for them are “emotions” and “justice”. Laws are made by people, they say. If a law is considered unjust, we don’t have to abide by it. On top of that, as victims of Japanese wartime aggression, they have the moral right to be respected.”

While the Japanese government wants to put the past behind it, and is only concerned about its present relations with its neighbour, Korea bases all its claims on past events. “The 1910 Annexation Treaty is actually the element on which the Korean Supreme Court’s decision is based,” OKUZONO says. “Korea’s position is that the treaty was illegal and extracted by force, and that, between 1910 and 1945, Korea was just a Japanese colony. In point of fact, the Japanese government does agree that Korea’s treatment was unfair. However, the way its colonies were ruled at that time was no different from what European countries were doing, and it believes it must be judged in that particular context. In this respect, the 1910 treaty was legal and legitimate.”

A recent troubling development in relations between Japan and Korea is that the two countries seem to be drifting apart. “It’s true,” confirms OKUZONO. “In many respects, Korea’s estimation of Japan is nowhere as high as before. For example, they used to worship Sony and Panasonic, but now the two companies combined are smaller than Samsung.

“In the past, particularly during the Cold War, America and Japan were Korea’s main diplomatic advisors. The end of the Cold War has coincided with Korea’s rapid economic growth and the appearance of China on the world stage. Now China has become Korea’s closest ally, both politically and economically. Above all, China has become Korea’s biggest market. Also, it’s the one country – much more so than Japan or the US – that has some leverage over North Korea and sees to it that the Hermit Kingdom doesn’t do anything too odd.

One problem is that the Blue House (the Korean equivalent of the White House) is now taking the lead in foreign policy. And none of President Moon Jae-in’s advisors are really knowledgeable about Japanese affairs. Everybody is just focusing on – is obsessed with – North Korea. Even America is only considered an important ally in so far as it can help manage North Korea.

“The same thing can be said about the Japanese attitude toward Korea. ABE doesn’t trust his Foreign Ministry, and nobody in his Cabinet knows how to deal effectively and sensibly with these matters. For example, someone who really knows and understands Korea would never have imposed export restrictions. The reason is that, from a Korean point of view, such behaviour amounts to bullying someone you consider weaker than you. They are reminded of what Japan used to do during the colonial period. In the circumstances, it was just natural for them to hit back with the same behaviour. To be fair, even the Korean government is guilty of such insensitive action. For example, I would think twice before imposing new checks on food imports from Japan. Fukushima’s triple disaster is still a fresh wound for many Japanese, and the current rift is no good reason for reminding them of what happened in 2011.”

OKUZONO believes that the recent developments following the Korean Supreme Court’s ruling could have dire consequences for the future of Japan-Korea relations. “It’s a little too early to say how our economies will be affected, but I wouldn’t worry about the restrictions on the export of materials critical to the manufacture of semiconductors and smartphone displays. I don’t think Korean production will be affected in the long run because ABE understands that increasing the pressure on this issue would have catastrophic consequences.

“What I’m more worried about is the effect that the current battle is going to have on Japan’s local economy, particularly tourism. Last year, 7.6 million Koreans – out of a pop- ulation of 50 million – visited Japan. That’s a huge number. However, the current fight has pushed many Koreans into boycotting Japanese products, and even those people who’d like to buy them or travel to Japan are intimidated by the general paranoia. If things don’t change soon, all those regions whose economy had benefitted from the recent surge in foreign tourists are going to be seriously damaged. Last but not least, and for me the most regret- table thing, is that South Korea has stopped all kinds of student and cultural exchanges. Actually, most Koreans don’t hate the Japanese. They only dislike the ABE government. Many of the people I talked to urged me to tell my students they should visit South Korea, and not to be afraid, because they like Japan and Japanese culture. That’s the most important thing. I don’t care if the governments fight. They’ll probably keep fighting forever. But involving the younger generation, the future of our two countries, is an unforgivable mistake.”

JEAN DEROME