The author of Coin Locker Babies is back with a novel that has a lot to say about Japan’s years of crisis.

The author of Coin Locker Babies is back with a novel that has a lot to say about Japan’s years of crisis.

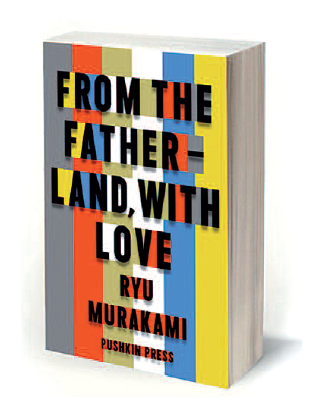

Murakami Ryu is a committed writer and observer of society who has been involved for many years in encouraging his contemporaries to reflect on Japan’s situation. Unlike the other famous Murakami of the writing world; Murakami Haruki, who writes on universal topics that reach a vast readership, Ryu is a Japanese writer whose topics concern the Japanese first and foremost. This doesn’t mean that a foreigner won’t enjoy reading him, but it will require an additional effort to understand all the novel’s dimensions, even though they may not concern parallel worlds such as Haruki’s latest international success, 1Q83. Murakami Ryu is an angry man who places his characters in the real world, or at least in a universe strongly inspired by the reality around him. This is very much the case in From the Fatherland with Love, recently published in English. First published in 2005, this 672-page book is political fiction written at a time when Japan was experiencing a crisis from which it couldn’t seem to escape after the financial bubble burst in the 1990s. The country had also lost its way on an international level, with the end of the cold war blurring the map of Asia and the United States ceasing to play a protective role towards Japan while it put all its efforts into developing its economy. Bereft of its all-powerful guardian, Japan now had to build its own identity in relation to its neighbors, which was handled incompetently. This is the context that motivates Murakami Ryu as he expresses his dissatisfaction and considers that the country needs to be shaken up. He transports his reader to the near future – April 2011 – and submits him to a trauma. This is not a question of an earthquake or tsunami as other writers such as Komatsu Sakyo, or the manga writer Kawaguchi Kaiji have already done that. Murakami Ryu has instead found another way to shock his readers by depicting an invasion from North Korea. Since the end of the Second World War and the creation of the Peoples Democratic Republic of Korea, relations between Tokyo and Pyonyang have been tense. The North Korean regime takes advantage of Japan’s economic weaknesses and the American withdrawal from Asia to lead an operation in which the Land of the Rising Sun falls under its power. The idea is simple. A command of a dozen elite soldiers takes the Fukuoka baseball stadium on Kyushu Island (the nearest to the Korean peninsula) hostage. 500 of them then take the city before sending in reinforcements of 120,000 men. In reaction to this act of aggression, which unfolds in the space of a week, the Japanese authorities are completely lost and display a level of indecisiveness that allows the invading Korean forces free reign. “Here in the crisis-management room, watching these people frantically at work, Yamagiwa Kiyotaka, chief cabinet secretary, got the same sour taste of futility that sometimes made him feel like saying to hell with it all. At first he thought it was because he’d been left out in the cold, but he was beginning to feel it was more than that. Being outside the frenzy of the round table, he had become painfully aware of the Japanese government’s inability to see the big picture – and if he could see it, no doubt other outsiders could see it too”. In just a few words, the author expresses his opinion of the paralysed Japanese government, while Pyongyang’s men are depicted as determined and efficient. As is this habit, Murakami Ryu did a lot of research before sitting down to write his novel. He met North Korean defectors in order to describe as precisely as possible what the Pyongyang invaders could be capable of. “There was no shortage of instructors in the art of killing people or blowing up facilities, but no-one in the Republic could teach you how to behave like a traveller from the puppet regime,” he writes, not without humour. It is rather violent though as the author aims to rouse the ire of his readership. Murakami is familiar with the use of violence in his novels as a reminder that it is often used as a means of expression in the last resort. Traditional Japanese society and its leaders are shown as too inflexible, too fossilized, to resist. “These Japanese simply weren’t used to violence; they lived in a soft, tissue-paper world”. The only ones capable of doing anything are not part of this antiquated system and we see a group of marginalized young people take control of the situation and lead the fight against the invaders. A lot was written about this remarkable novel following its release in Japan. The timing of it’s 2013 release in Great Britain might seem a bit strange following the shock of the terrible tsunami in 2011 and the consequent changes it provoked. Nevertheless, From the Fatherland with Love reads like a historical chronicle from which we can learn much about the Japan that Murakami is critical of, yet to which he is deeply attached.

G. B.

REFERENCE

From the Fatherland with Love by Murakami Ryu,

translated by Ralph McCarthy, Charles De Wolf and

Ginny Tapley Takemori, Pushkin Press, 2013