In his restaurant located in the heart of the capital, chef KAIBARA offers a wonderful culinary experience.

An expert on the cuisine of the Edo period (1603-1868), KAIBArA Hiroshi brings us a taste of the past.

At the bend of an alleyway in an anonymous neighbourhood, neither the sombre facade nor the tiny interior in the style of a local bistro would lead you to think that this was a special restaurant, let alone a rarity in the Japanese capital. In this restaurant called Taika, you can enjoy cuisine from the Edo era, which began in the 17th century and ended during the second half of the 19th century when Japan opened its doors to the world.

It was during this period that the foundations of the current Japanese cuisine were laid with the appearance of the stars of Japan’s food: soba noodles, tempura, grilled eel or sushi (as we know it today). Restaurants proliferated in the city streets in response to the demands of a workforce that arrived in droves to work on the construction sites of the new capital. The above-mentioned dishes were served from stalls and were the fast- food of their day. However, even the Japanese have only a vague idea of the cuisine of this period and don’t really know what it was like. Of course, it’s not easy to summarise the history of the 250 years of the Pax Tokugawa or its cuisine, which both underwent several changes. Even the seasoning, without mentioning the basic products, were not completely identical to those used today. Kombu (edible kelp) was not used for dashi, the stock was made solely with katsuo- bushi (dried bonito fish), which gave it a lighter aftertaste. Soy sauce, an iconic ingredient in today’s Japanese cuisine, took some time to spread to the east of Japan and, before the 18th century, it was more usual to use a condiment called irizake, made from reduced sake and salted plums, and some- times with katsuo-bushi. It has a less pronounced taste than soy sauce, allowing the flavours of the other ingredients to reveal themselves. Sashimi were eaten with irizake, which goes better with whitefish or shellfish. Even the miso (fermented soybean paste), called Edo miso, which the locals simply called “red miso”, was different. The pro- portion of rice koji was higher than in other miso, and meant fermentation could take place in the relatively short time of two weeks in order meet the demand, which was much greater than the supply. The flavour of this miso was more delicate and fresh, less persistent than if sugar is added to the dishes, as is usual today.

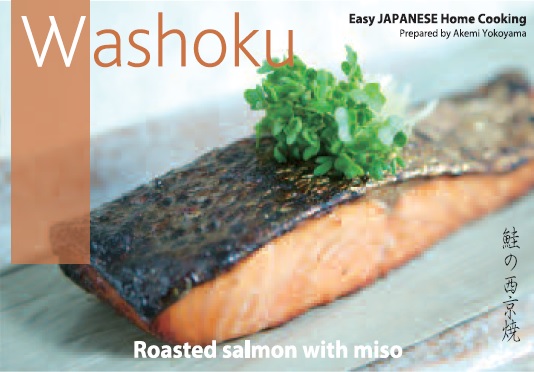

This all means that when eating the food served at Taika, you’ll be agreeably surprised by the delicacy and lightness of the flavours. This cuisine is imbued with a kind of simplicity and serenity, whatever the ingredients or method of cooking. It’s an experience that’s quite the opposite of the image we have of reconstructions of historical dishes, which we imagine to be plain, heavy and unrefined… It’s a very pleasant surprise.

according to chef KaIBaRa Hiroshi, these distintive features stemmed from the character of the people of the Edo period, who liked neither excess nor frills. we can really taste the flavour of each ingredient whose qualities are presented simply and are unadulterated. Today, we often compare the cuisine of Tokyo with that of Kyoto, considering the first to be greasy, salty and strong- tasting, while the second is seen as sophisticated, delicate and harmonious. However, when eating at Taika, you realise that, historically, it’s far more complex than we tend to believe.

Of course, this delightful experience is due in large part to the talent of the chef, KaIBaRa. Trained as an Italian cook, he became passionate about historical cuisine, and decided to retrain in Japanese cooking. He researched the Edo period for ten years before opening his restaurant in the Shiba district, cradle of the Edo culinary style, and whose local prawns still bear the name shibaebi prawns. This area located close to today’s Ginza shopping district and Tokyo station, was once a beach you could walk along and catch shrimp, shellfish and small fish, which were abundant.

The reason that this chef, as well as other restaurants specialising in the cuisine of the Edo era such as Nabeya, now closed, or Yaozen, founded 300 years ago, can produce these menus, is because there are many documents surviving from the period. Of course, the description of the recipes is more or less in “summary” form (that’s not to say that the cooking methods were imprecise: at that time, the obvious details were not noted down), but what was written was enough to help people understand how to pre- pare the food.

The chef explains to us that the dishes served in the restaurant remain faithful to the visual appearance of the food of that era, thanks to prints of the period. These also help us under- stand the customs of the time: there were stalls, forerunners of the izakaya (Japanese bistros), which only served food to accompany sake, such as baked potatoes, wild boar or grilled tofu, and hens’ eggs were more expensive than their meat… Each dish has a story, a meaning, from which we can learn something. If you feel like it, you can eat them all accompanied by Edo Kaijo, a sake brewed in Shiba district.

If you understand Japanese, you can have a real lesson in historical cuisine, as the chef will explain the origin of every dish in detail. a foreign traveller will feel equally at home in this restaurant with its warm and peaceful atmosphere (the chef wants to create a space where you can enjoy a moment alone) while on a journey back in time to a distant period brought to life through different flavours. That’s the magic of cooking.

SEKIGUCHI RYOKO

PRACTICAL INFORMATION

TAIKA 2-9-31 Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo

Tel. 03-3453-6888

Open from 18:00 to midnight. Closed on Saturday.