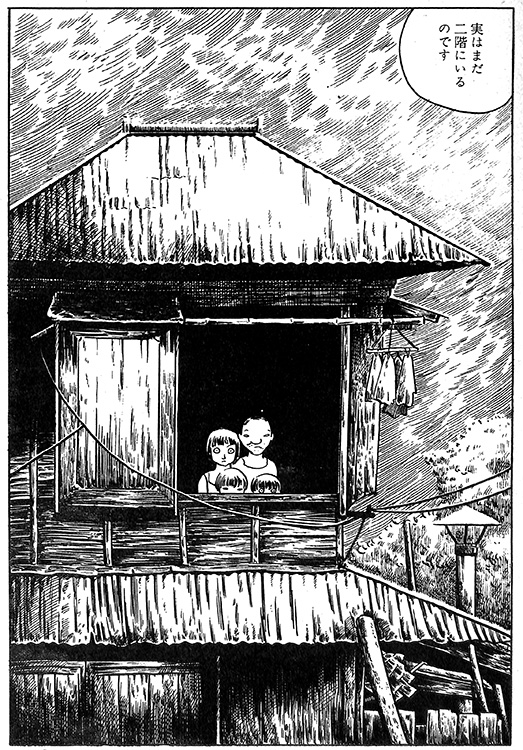

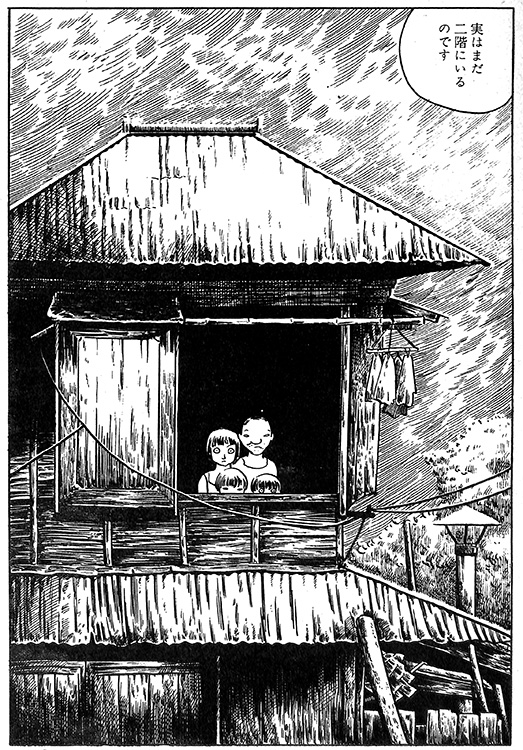

Taken from “Ri-san ikka” (The Family of Mr Lee), which first appeared in issue no. 34 of Garo (June 1967, pp. 177-188).

For the first time in France, the entire work of this manga genius has been published in translation by Cornelius.

The best works of art are those that stay with you for a long time; novels and films and paintings to which one returns again and again. In this respect, Tsuge Yoshiharu’s manga constantly challenge the reader; his quirky, sometimes inscrutable stories constantly challenging us to find new hidden meanings. Funnily enough, some of his best-known stories – “Neji-shiki” being a prime example – even lure us into imagining things that simply are not there. Scores of critics, commentators and psychologists have come up with the most outlandish interpretations of this short tale – the nightmarishly hallucinatory wanderings of an injured boy around a seaside village – while Tsuge himself insists to this day that there’s no deep meaning whatsoever to be found. That said, we can’t deny the role played by Tsuge’s manga in inspiring the development of Comics Studies in Japan. Manga shugi (Manga-ism, see p.8), arguably the world’s first magazine devoted to manga criticism, was co-founded by Garo editor Takano Shinzo (under the pen name Gondo Susumu) in 1967, just two years after the magazine had begun to publish Tsuge’s literary comics. Kawamoto Saburo is one of Tsuge’s closer and more perceptive acquaintances, devoting insightful articles to the elusive artist. In his essay collection “Toki ni wa manga no hanashi o” (Let’s talk about manga sometimes), for instance, he praises his comics for having, in this age of high-speed information, a particular healing power. According to Kawamoto, one of the less talked-about aspects of Tsuge’s art is its “Japanese-ness.” “While in the 1960s and 70s Japanese society was busy importing all kinds of Western habits, he became interested in the native customs that were being rapidly forgotten, casting a new light on traditional culture while avoiding nostalgia,” he says.

A typical example can be found in “Red Flowers”, a story where the heroine’s appearance (she wears a summer kimono) and behaviour seem to be untouched by modern life. Seemingly unaffected by contemporary life (represented by the tourist from the city who is in search of a good fishing spot), this teenage country girl – looking at the same time both innocent and strong – maintains her slow-paced lifestyle according to traditional habits and values, surrounded by luxuriant forest, which elsewhere in Japan has been chopped down in the name of progress and economic interests. “Tsuge was particularly attracted by nature and quiet, secluded places,” Kawamoto says. “That’s one of the reasons he liked Chofu so much. He moved to Tokyo’s western suburbs primarily to start a new job, but after experiencing poverty in the city’s poor districts of Tateishi and Kinshicho, Chofu certainly was a breath of fresh air.” Even in “Neji-shiki” one can find many aspects of traditional culture. Though most critics have highlighted the story’s absurd and irrational elements as well as Tsuge’s contribution in bringing Japanese comics into the world of literature and surrealism, this manga can be also interpreted as an allegory about the country’s inability – or unwillingness – to accept the death of the young soldiers who died during the war.

Speaking of literature, Kawamoto sees Tsuge as following in the same tradition of such writers as Ibuse Masuji and Ozaki Kazuo, as his stories highlight the same kind of detached humour. Indeed, Tsuge has admitted (in an interview with Gondo/Takano) to being influenced by Ibuse. The Hiroshima-born author may be better known in the West for “Black Rain” – a story about the atomic bombing, which was made into a film by Imamura Shohei – but in Japan he was also famous for his many humorous novels.

One story by Ibuse that directly influenced Tsuge is “Sanshouo” (Salamander), the tale of an overgrown salamander that gets stuck in a hole in its underwater cave and experiences mood changes while reflecting on its predicament. Tsuge, again, told Gondo that he had read Ibuse’s story, and though he didn’t particularly like it, it inspired him to create his own “Sanshouo” in 1967. Tsuge’s manga of the late 1960s are often seen as the comic version of the I-novel (a sort of typically Japanese confessional literature). “Writer Kurumatani Chokitsu has pointed out that there are two different kinds of autobiography in Japanese literature: one that deals with a public persona (jiden) and one that deals with more private affairs (watakuchi),” says Kawamoto. “Tsuge’s Icomics belong in the latter category. As Kurumatani says, I-novels question the root of one’s being – this ominous, mysterious and unknown part of us, which remains hidden in the ground of our daily life.

” Kawamoto is a big fan of (and has written books about) author Nagai Kafu. Though Nagai was born in the 19th century, Kawamoto sees a sort of distant connection between his writings and Tsuge’s comics. “Nagai elevated Shitamachi – especially the blue-collar districts east of the Sumida River – to new poetic heights, while Tsuge rediscovered the Japanese countryside and other unglamorous, forgotten places.”

As Kawamoto wrote in “The Poetry of Melancholy”, Tsuge strongly disliked any sign of modernity. On the contrary, he felt an attraction for those rundown places that had been left behind by Japan’s rapid postwar economic growth. “He felt good walking the city’s backstreets and drab alleys, which most people tend to avoid,” he says, “and sought out the bleak, depopulated hot-spring villages in Tohoku. To him, these seemingly charmless places were a sort of Shangri-la.”

It’s as if Tsuge applied to travelling the same principles of that most Japanese concept: wabi-sabi, or the aesthetic idea based on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. “Even when it came to the seaside, he didn’t visit the fashionable East Izu resorts like Atami, but the very different small villages on the west coast; not the popular Shonan beaches just south of Yokohama, but small windswept fishing ports like Ohara, in Chiba Prefecture, where he lived as a child, and which, as an adult, he later visited many times.”

In Tsuge’s travel stories, his characters often experience a sort of déjà-vu. In “Gensenkan no shujin” (The Master of the Gensenkan), for instance, though it’s the first time the protagonist visits this hot spring, he can’t help feeling as if he’s known the place for a long time. “I once attended a Donald Keene talk,” remembers Kawamoto, “where the famous American scholar and translator pointed out an interesting thing: he said that in the modern era, people from the West – think about the European explorers – had looked for places where nobody had been before; the Japanese, on the other hand, long to visit places where other people have already been. That’s typically Japanese, he said.”

One last example of Tsuge’s “Japanese-ness” is “Nishibetamura jiken” (The Nishibeta Village Incident, 1967), another story about fishing which turns into a manhunt (looking for an escaped mental patient) and towards the end gets weirder and almost nonsensical. “Fish play a starring role both at the beginning and end of the story,” Kawamoto says. “As Tom Gill pointed out, Tsuge’s little fish come from a strong cultural tradition, in which fish and their environment are metaphors for the human condition, and the fish swimming away at the end of the story can be seen as a symbol of disappearing or vanishing. This idea relates to Zen Buddhism and the concept of mu (nothingness). In many of Tsuge’s works, his male characters drift away and abandon the modern world in search of some sort of enlightenment, or peace of mind at least. In other words, many of Tsuge’s stories come from a long tradition of world-renouncing, romantic losers.”

GIANNI SIMONE