During the past few decades, the extent of Japan’s influence on the Western art world has been revealed.

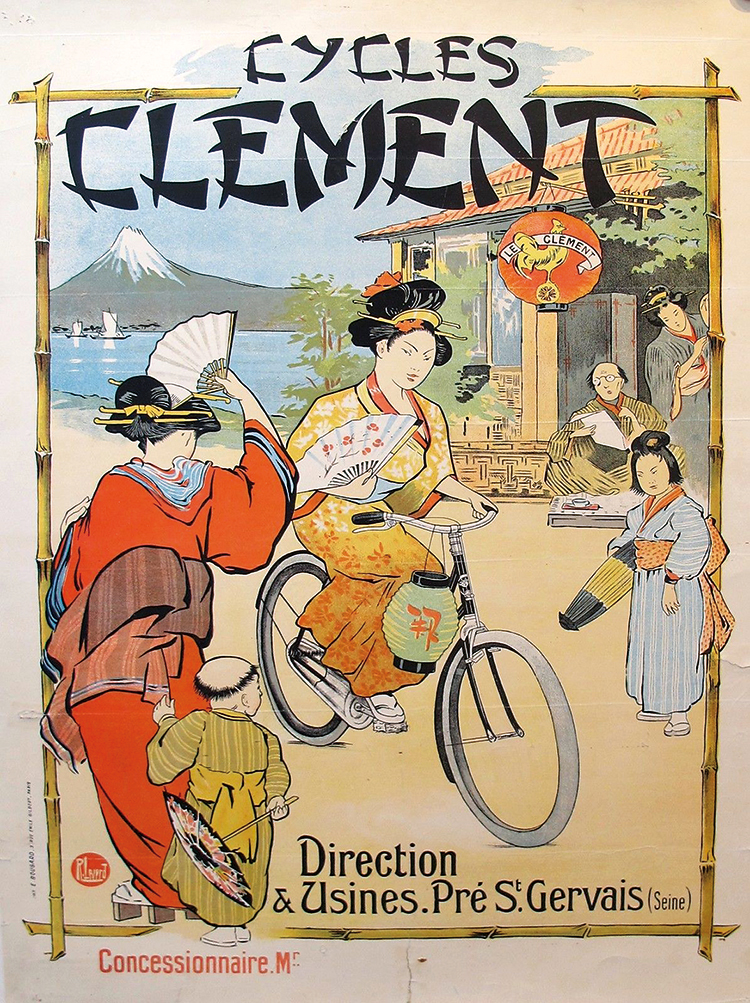

This poster for Clément bicycles, circa 1900, illustrates the Japanese influence.

The word “Japonisme” came into being after the successful visit of Japan’s official envoy to the 1867 World Fair in Paris. It was soon on everyone’s lips, thanks notably to articles by Philippe Burty, in 1872 and 1873, in La Renaissance littéraire et artistique, which coined the term to describe the fashion for Japanese objects and prints. The trend quickly outgrew the number of items available, which were often sold for very modest amounts. The market for Japanese art centred on Paris and London, but Holland, Germany and Austria were not far behind.

The 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and Japan was signed following the one between The United States, Russia and Great Britain. It partially ended Japan’s isolation dating back to the 17th century, and was enough to arouse the curiosity of enthusiasts and artists. In the period after the Paris Commune (Radical socialist and revolutionary government, 18 March to 28 May 1871), Henri Cernuschi and Théodore Duret left on a world tour. Cernuschi brought back a large collection of Japanese artefacts, which he presented to the Palais de l’Industrie (Palace of Industry) in 1873, and which was principally made up of bronzes from which artists were allowed to make copies.

It was Cernuschi who advised the art dealer Philippe Sichel to travel to Japan to take advantage of the situation following the modernizations of the country after 1868. The Emperor Meiji had decided that was the best way to demonstrate what Japan could achieve, and thus avoid the sad fate suffered by China with the destruction of the Old Summer Palace in the summer of 1860. Sichel brought back 450 cases of objects: books, prints, “foukousas” (squares of printed or embroidered fabric), and also theatrical costumes and masks, due to the demise of Noh Theatre troupes after their patrons, the daimyo (see Zoom Japan no.79, April 2018), had disappeared. Their former swordcarrying protectors had been made redundant with the suppression of the Samurai in favour of a modern army trained by European instructors, mostly from France.

After the World Fairs held in Vienna in 1873, and Philadelphia in 1876, the World Fair in Paris in 1878 prompted an enthusiastic response from critic Ernest Chesneau, and he wrote two articles in the Gazette des beaux-arts entitled “Le Japon à Paris” (Japan in Paris). The market was expanding, with more and more artists adopting the forms, composition, colours and techniques used to produce Japanese objects and prints. Siegried Bing, the dealer in arts from the Far East, had travelled to Japan in 1880, and had brought back prints from the 17th and 18th centuries, notably those by Utamaro, and Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. He published a monthly journal, Le Japon artistique (May 1888- April 1891), and then transformed his art gallery in 1895, calling it “L’Art Nouveau” and began to support “japonisants”- Western artists influenced by Japanese art.

At the World Fair in 1900, the displays of ancient Japanese art made people realise that, up until then, they had only known about more recent art, though they had been aware of the decorative motifs of katagami (stencils), which had arrived in great numbers at the end of the 1880s when textile printing had been modernised in Japan; their influence was felt from the start of the 20th century up until 1925-1930 and the designs of the decorative Art Deco style.

Japan had been isolated due to international politics and its engagement with Germany until the end of the Second World War and its final defeat. Then, in 1961, at Les sources du XXe siècle (Sources of the 20th century), an exhibition at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris organised by the Council of Europe, not one word was said about the Japanese influence on the European Art Nouveau movement, including such well-known artists as Klimt, Gaudi, Gallé among many others, despite the fact that France had signed a peace treaty with Japan in 1952.

In fact, Edmond de Goncourt, an enthusiast from the very beginning, was able to write in his Journal on 19 April 1884 that “Japonisme was revolutionising the perspective of Westerners….”. but it wasn’t until 1968, when a UNESCO project The contribution of Japan to modern art took place in The National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, that the mutual and beneficial influences between Japan and the West were noted. This was followed, in 1976, with a book from the Japanese publisher Kodansha, edited by Chisaburoh F. yamada, with an English edition entitled Dialogue in Art. Japan and the West.

In 1974, Colta Feller Ives had organised an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New york called The Great Wave. The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints, based on the work of James Tissot, Manet, Degas, Van Gogh, Vallotton, Mary Cassatt, Bonnard, and Toulouse-Lautrec. In 1975, an exhibition in the United States, which visited Cleveland, Baltimore and Rutgers University (New Jersey), was the first to use the term Japonisme in its title – Japonisme. Japanese Influence on French Art 1854- 1900. It highlighted the impact of Japaneseillustrated books, as well as the prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige, on artists such as Bracquemond, Manet and Whistler during the years from 1864 to 1870, and studied their influence not only on engraving and painting but on decorative art right up until the end of the century.

In 1979 – 1980, three Japanese museums in Tokyo, Osaka and Fukuoka illustrated the theme of the connections betweenthe prints and Impressionist painters: Ukiyo-e prints and the impressionnist painters. Meeting the East and the West. They did this on the occasion of an international conference in Japan’s capital city, which brought together Japanese and Western researchers whose findings were published in 1980 under the title Japonisme in art. This was also the theme of a book by Swedish writer Jacques Dufwa, published in English in 1981, Winds from the East: A Study in the Art of Manet, Degas, Monet, Whistler, 1856 – 86, in which he insisted that Japonisme had influenced the innovative painters of the last third of the 19th century.

In 1980, the German art historian and academic Siegfried Wichmann published a large work with over a thousand illustrations: Japonismus, translated into English in 1981, then into French in 1982 under the title Japonisme. Besides the painting and engraving of various European artists, not just from France, such as Odilon Redon, but also from England and Germany, he deals mainly with the decorative arts, ceramics and glass from the end of the 19th century, as well as garden design and calligraphy.

In 1988, the exhibition Le Japonisme held at the Grand Palais in Paris and at the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, was international in outlook and displayed examples of Japanese influence on Western Europe and the United States in all areas of art and design including architecture and photography. With 150,000 visitors in France and three times that number in Japan, the word was on everyone’s lips. At the time, the influence of Japonisme in Eastern Europe was unknown, but that was to change very soon with the fall of the Berlin Wall. In the following years, European countries all reflected their links with Japan in their own ways. Whereas the 1988 exhibition concentrated on trying to show the changes in artistic techniques, from painting to the decorative arts, brought about by the discovery of Japanese aesthetics at the end of the19th century, Holland’s connection with Japan had continued during the time the latter had remained isolated from the outside world, due to the Dutch trading post on Dejima in the bay of Nagasaki, and in 1989 they were on an even keel. At the time, the exhibitions in Japan were exploring the subject in relation to France, then from 1990 onwards, they repeated the experience in Poland and the United States (twice), and Vienna where, with the help of numerous katagami (stencils), they demonstrated the role they had played in the Viennese Modern Age. They toured Great Britain in 1991, then Finland in 1994, while in 1996, the Galliera Museum in Paris, in conjunction with Kyoto, staged Japonisme et mode. (Japonisme and fashion). Belgium regularly spotlights its collections of Japanese art, and in 2002, Takagi yoko published his thesis, Japonisme : In fin de siècle Art in Belgium. Florence in 2012; Barcelona and Madrid in 2013-2014; Prague in 2014; Helsinki, Oslo and Copenhagen in 2016; Budapest in 2017; all explored Japonisme in their respective countries. But exhibitions with more general themes continue to take place elsewhere, in the United States, in 2011, and in Essen and Zurich, in 2014 and 2015. It was at this time that, in Paris, the book Japonismes, edited by Olivier Gabet, was published, using the plural form of the word for the first time. It’s true that, with the passage of time, the meaning of the word will come to reflect the various styles and techniques used in painting, sculpture and the decorative arts.

GENEVIÈVE LACAMBRE*

*Honorary General Heritage Curator