The hill of hope (Yubari kibo no oka) has lost some of its splendour, but the city council hopes that all is not lost.

Though Yubari is the poorest city in Japan, its inhabitants and those in charge believe in its future survival.

Japan is frequently portrayed as a laboratory where all the changes the developed countries want to see during the coming decades are tested first. To get a better idea of the challenges facing us, and how a courageous town council is trying to solve them, you need to go to Yubari. Situated about 90 minutes away from Sapporo by car, the city was one of the largest mining centres in the archipelago. At its height, it had 120,000 inhabitants, lots of cinemas, even a 5-floor department store. Today, there are fewer than 8,700 inhabitants, 50% of whom are over 65 years of age. Since the last coal mine closed down in 1990, Yubari has appeared in record books worldwide. It’s population is by far the oldest in Japan, with an average age that will reach 65 in 2020. Yubari, which once had 22 elementary schools, 9 middle schools and 6 secondary schools, now has only one of each.Today, there are only 75 secondary school pupils compared to 130 in 2007. You never come across a young person when walking through its often deserted streets. Only one person in 20 is under 15 years of age. Yupari’s demographic situation is extreme, but it reflects the present tendency in the archipelago where you can already imagine that towns and villages might end up disappearing completely in the coming years. In 2014, in his book Chiho shometsu (“The Demise of the Regions”, published by Chuokoron Shinsha, not available in English), former civil servant Masuda Hiroya advances the idea that this could happen to 896 local authorities by 2040. Yubari would like to escape this destiny, and has held on to its status as a city, but in name only as, in Japan, its usually necessary have at least 50,000 inhabitants to have the right to do so. But the authorities have not sought to give it the final coup de grâce, especially as, in 2006, it was the first and only local authority to become bankrupt. It was a black year for its inhabitants who, at least those who chose to stay, had to pay the price for a badly thought out development policy based on tourism despite the fact that the city, located at the end of a small railway line, was incapable of attracting thousands of tourists. Furthermore, Hokkaido as a whole was already lagging far behind in the tourism sector. The enormous amusement park built around the theme of mining soon proved to be a financial black hole that bankrupted Yubari. Today, practically nothing is left of the ambitious project apart from a few empty buildings, which gives it the air of a ghost town. No district in the town escapes from this impression of decline and decay, including the town centre where stray cats occupy the deserted houses, some of which are barely still standing.

It’s here that you’ll find Nonkiya, a restaurant owned by Yasuda Yoko. She is 74 years old, and inherited it from her mother who died in 2012. She serves ramen (noodle soup) to a dwindling number of clients. “In any case, I can only fit in 5 people at a time,” she says smiling. Yasuda Yoko lived for several years in Saitama, to the north of Tokyo, before coming to Yubari to look after her mother, and eventually succeed her. She hopes that Yubari will survive, and believes that the young mayor, Suzuki Naomichi (see pages 7-9), who was elected in 2011 aged 30 by an electorate much older than him, is capable of revitalizing the city or at least giving it the means to prevent its disappearance. It has already benefitted from the young mayor’s initiative to create a more compact city, which allows the inhabitants access to public services located near to where they live. It should be noted that Yubari is spread out over an area of 763 square kilometres, making it the largest town in the archipelago. Managing this vast area is complicated and costly. For the city’s Mayor, it’s imperative to refocus services and housing centrally, so that the inhabitants can benefit from a better quality of life.

The yellow handkerchiefs symbolizing eternal devotion in the film Shiawase no kiiroi hankachi (The Yellow Handkerchief) by Yamada Yoji can still be seen in Yubari.

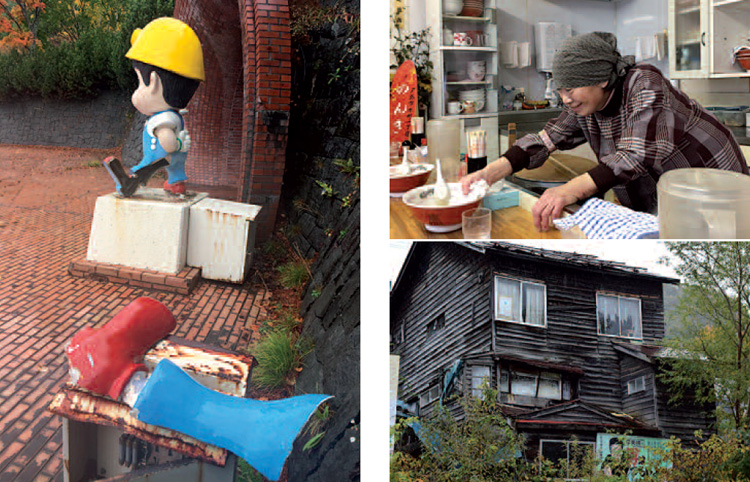

Yuchan, the city’s mascot, is in a bad state, like many of the houses abandoned by a large part of the population. But Yasudo Yoko, owner of Nonkiya, is still smiling.

There’s still much to be done, as the 24-hour mini-market is more than 1.5km from the city centre. At night, it’s not unusual to come across foxes on the badly lit road, which come down from the surrounding hills and hang out in the deserted town. It’s a phenomenon seen in other parts of Japan, particularly where the population is in sharp decrease, confirms the taxi driver who is taking us to the mining museum. “I take great care when its dark. I’ve often seen foxes crossing the road. They sense that people are leaving the city in droves.” Though it’s impossible to imagine that Yubari will experience a demographic revival, the town council wants to attract visitors to help revitalize the local economy. Apart from the incredible local hospitality, Yubari can rely on its illustrious past, and is modernising the mining museum. It can also exploit a certain mystique surrounding the city, which endures throughout the country thanks to numerous very popular films made in the1970s at the height of the Showa era, when Japan’s economy was the second strongest in the world and its people were happy to be alive. One of the most famous of these long feature films is Shiawase no kiiroi hankachi ( The Yellow Handkerchief, 1977) by Yamada Yoji (see Zoom Japan No.30, April 2015), starring the great Takakura Ken and the talented Baisho Chieko. A few kilometres away from the city centre, you can even visit a reconstruction of the film set and see the famous yellow handkerchiefs, symbols of undying devotion. While there’s life, there’s hope, as they say. In Yubari, the prospect of scaling the “mountain of hope” ( Yubari kibo no oka), holds little attraction, it reminds us that we must always retain the willingness to take action if we want to escape our fate. The city is “a microcosm of what Japan will be in 2050,” explains the hospital manager, aware of having to fight to get the resources to improve the life of the inhabitants. Nostalgia for the Showa era is so prevalent that Yubari is able to arrange a visit for present-day retirees — some of the most well-off people in the country — so that they can rediscover a bit of this period atmosphere. A local curiosity is the colourful cinema posters displayed on many buildings in the city centre. Here, you can come across the face of Alain Delon in Plein Soleil (Purple Noon), or Atsumi Kiyoshi in Otoka wa tsurai yo (It’s Hard to be a Man). The art of cinema is still a safe bet for the city that hosts the only science-fiction festival in the country, which has attracted some famous festival goers such as Quentin Tarantino. Following his visit, the filmmaker named one of the characters in Kill Bill 1 in honour of the city.

And then there are the famous Yubari melons, thanks to which the city’s name makes the headlines every year when the record breaking melons are sold at auction. In March of last year, two melons were sold for 3 million yen (£ 21,500). All in all, there are many good reasons to believe that things are not as bad as they seem.

ODAIRA NAMIHEI

Leave a Reply