In charge of Yubari since 2011, Suzuki Naomichi is fighting to transform the city.

In your official position, what have you done to become the symbol of a Japan, and a city, that refuses to die?

SuzukINaomichi :The Tokyo Olympic Games will take place in 2020, and five years later, in 2025, the capital’s population will start to decline. We are a developed country with a diminishing and ageing population. We’re short of money and our debt is abysmal. Yubari is particularly affected by this situation: It has the highest levels of depopulation in the country; in fifty years, the number of inhabitants has fallen from 120,000 to 8,000; the young people have left the city; and coal mining is no longer possible, causing the city to default on its debts. Japan is a developed country facing difficult problems, which have appeared here before they’ve become apparent elsewhere. Yubari is the best example of this phenomenon. The subject was raised at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos in 2013. At that time, I had been named Young Global Leader, and I said to myself, yes, it’s true that Yubari has problems, but if it manages to overcome them, it could be a template not only for Japan but for other developed countries, which will inevitably have to face the same problems at any given moment. That was the goal I decided to focus on.

On you visiting card is the slogan “Restart Challenge More”. Can you explain it to me?

S.N. : After the city became bankrupt in 2007, an organisation to relaunch public sector finance, unique of its kind, came into being. The country is made up of 1,700 municipalities, yet Yubari is the only one to have such an organisation. For ten years, we did the best we could and paid back what we owed. The revenue that the municipality is able to generate has risen to 800 million yen (circa £ 5.5 million), and we have to pay back 2,600 million yen (£ 17.2 million) on average each year. It’s very hard. One day, I gave a press conference in Tokyo, and a foreign journalist said that I should have called it “Mission impossible”… However, we’ve managed to pay back 11,600 million yen (£ 76.9 million) in ten years, by putting unprecedented austerity measures into place. For example, our six primary schools were amalgamated into one, the same went for the three secondary schools. We imposed the highest taxes in the country, and civil service salaries were reduced drastically. Thanks to all that, we’ve been able to repay what we owed, but it was especially difficult as so many people had left the city. In ten years, we’ve managed to pay back 11,600 million yen, but we‘ve lost 30% of the population. Consequently, those remaining must continue paying back while the situation continues to get worse, it’s a vicious circle. So we have a double mission. The first is to clear the debt, the second is to improve conditions for the inhabitants. These two goals are a bit like applying the brakes and the accelerator in a car at the same time, but we have to make the most of the situation. In this context, in March 2017, I suggested to the government that we should change our priorities. The suggestion was accepted. The overriding priority to pay back the debt was put to one side in favour of a combined effort to jump start the economy. It’s a new start; we’re working on two fronts at once. I wanted to move away from: “There are fewer and fewer people, less money, and there’s nothing we can do…” to: “Let’s take up the challenge”. It’s from this perspective that we adopted the slogan in order to encourage people’s involvement.

Did your past experience as a civil servant in Tokyo prove useful in your negotiations with the government?

S. N. : Previously, I was effectively working for the the city of Tokyo, whose population had reached a total of 13 million. With 160,000 civil servants, it’s the largest local authority in the world. I worked there for 11 years and 8 months. I knew nobody in Yubari, so I was a bit disconcerted to begin with. But in a situation where you want to make fundamental changes to the city, it can be an advantage. In fact, if you live somewhere for a long time, you forge strong links with people, which can be a good thing, but if you want to completely change things, those ties can become problematic. In that sense, you could say that my experience in another administration, admittedly not at the same level, allowed me to do my job properly without, let’s say, “having to answer to anyone”. I think that’s why people wanted me to make bold changes. Even if it wasn’t necessarily a prerequisite, I think it was a good thing.

What has changed since your election 6 years ago?

S. N. : Yubari is the only city in the country to have ever been made bankrupt. However, more than 82% of the electorate voted in the mayoral election, whereas in Tokyo, it was around 40%… I often compare the administration, the public services, to the air we breathe. Air exists, it’s obvious, we can’t imagine life without it. If it starts to disappear, it becomes a problem. But in Yubari’s case, the air suddenly became completely unbreathable, that’s why the inhabitants began to ask: “What can be done?”. For me, what’s really changed in the attitude of the inhabitants over the last six years, is that they realized they cannot depend on the city council forever, and they had to do something themselves. They are no longer simply asking for handouts, but ready to ask: “What can I do?”. They might not have reached this point if the city had never been made bankrupt. If you ask them about what’s going on in the city at the moment, they’ll mention the compact city project or the decision to close the JR Line. People should be able to talk about these things together and reflect on what needs to happen in the city, it’s just as important as local self-government. Obviously, it would have been better if people had realised this earlier, but human beings inevitably search for the easy way out. For me, that’s the biggest change the inhabitants have made.

The efforts demanded from the population over the last few years are starting to bear fruit. Are there one or two examples of which you’re particularly proud?

S. N. : The concept of a compact city, which I mentioned earlier. Yubari extends over a larger area than Tokyo. Previously, there were 100,000 inhabitants living in 763 square kilometres. Now there are just 8,000 people. So we had to concentrate the city’s utilities, housing and services, but people don’t like moving. We talked with them and tried to convince them over a period of six years. Finally, 6% of the population, of all ages, agreed. That represents 300 homes. Maybe it’s hardly even 6%, but I think it’s amazing that a city can change to this extent, and people can agree to make such an effort. One of them was a man aged 98, head of a local association, who’d refused to move 6 years ago. He was finally convinced, and made the move. You know how harsh the winters are in Yubari. When spring arrived, I went to his new home and he said to me, “It’s the first time I’ve been so warm in winter.” Can you imagine? He was 90 years old at the time. That means he’d been cold for 90 years. He’d been adamant about not moving, I find it extraordinary that he took the plunge. It gave me a real boost.

I’ve heard it said that you went door to door in the attempt to be elected mayor. Are you still as close to the population?

S. N. : Yes, of course! And I’ve set up a system that’s quite unique. If five people get together, I will meet them. I do that 365 days a year. I call these meetings “Let’s talk with the Mayor”. Though this system is in place, there are still people who dare not call me, so twice a year I travel here, there and everywhere to bring them up to date with the latest issues. When we first began to talk about a compact city, people were against the idea. Then there were others who were for the idea, which led to two rival groups. At the beginning, I remarked that, in the near future, the city was doomed to disappear if we did nothing about it. Even so, some people were still opposed to the idea. I was called upon time and time again as a result of the five people together idea. I was always being yelled at, but I learned something: human beings can’t be angry for more than three hours in a row. There comes a moment when they get tired… I just sit and listen to them. Then if I say to them: “So, at the moment, this and that is what happens…”, they reply: “Mmmh…”. They don’t really want to agree, but they’ll say: “So, this and that is what happens”. What I mean to say is that when you don’t know the facts, it’s easy to oppose an idea. On the other hand, if you know that you have several choices in any given situation, A or B, for this or that reason, it’s more difficult to oppose the idea because you understand the issues. If, however, you don’t understand, you say to yourself that option A is “a real pain”, option B “Oh no, that’s not for me”… it’s easy to oppose the idea. That’s why I believe in these sessions to explain things.

Do you sleep well at night?

S.N. : Of course! Around 5 hours a night. On the contrary, it’s my wife who tells me I give speeches in my sleep. And as that wakes her up, she tells me to go to sleep again before she… (laughs).

On a more serious note, are these meetings a new way of doing politics?

S.N. : I don’t know. If you decided to the same thing in Tokyo, it just wouldn’t be possible. There are too many people… There’s a certain way of doing things in small cities. If there are a large number of people then the city is strong. But if there are only a few people, it’s difficult to live without mutual support, we need one another. This might seem to be a detour, but, in fact, it’s a short cut: in order to have a framework where everyone is in a position of strength, you need mutual support. You know, Yubari has a larger proportion of elderly people than any other city in Japan: those aged over 65 represent 50% of the population. When I became mayor I was 30 years old, I was the youngest mayor in Japan. That’s quite unique: the city in Japan that has the highest number of elderly people elected the youngest leader in the country. It’s an odd choice. Working in Yubari, I’ve told myself that it’s perhaps a good thing. Here are all these elderly people with so much experience, who represent an important resource to support me, their mayor.

Is what you’re doing here in Yubari being observed by cities or regions of a similar size, and are they tempted do do the same?

S. N. : You know, the situation for Japan itself is worse than here in Yubari. On the city’s website (www.city.yubari.lg.jp/syakintokei/index.html) there’s a “debt clock” indicating that we’re repaying 70 yen per second. The country as a whole, is seeing its debt rise by 81,500 yen per second. So Yubari is well on the way to reflation, whereas the country’s financial situation is becoming more and more fragile. The problem is that the inhabitants of Yubari are also citizens of Hokkaido Prefecture, and Japan, too. As a result, even if Yubari becomes healthy again, it’ll be a problem if the situation deteriorates in Hokkaido or the country as a whole. If Japan decided to adopt a different system, I think the example of Yubari could serve as a model.

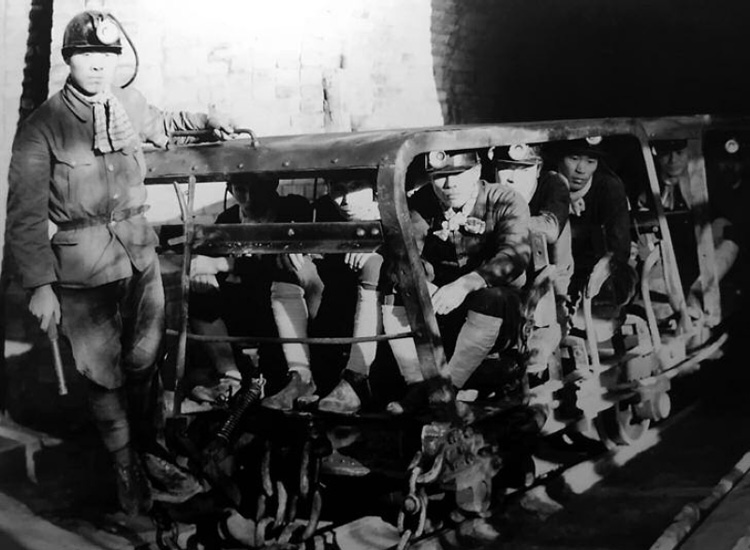

The mining operations in Yubari gave birth to the idea of ichizan ikka, which the young mayor holds dear.

Do you have a specific goal you want to achieve in the coming years?

S. N. : A year after my election, in 2012, I was told that the population of Yubari would fall by a half, to just 4,000 inhabitants. I think that even if this were to happen, making life more practical for people and improving their quality of life, would also improve their sense of wellbeing. My mission is to achieve enough to ensure that more than half of the people who are still in Yubari are happy that they stayed here. When I started, I was told that my job of mayor was to make sure the population increased. In fact, the population of Japan is decreasing, and we need to change this mind set. In another election, a mayor said: “I am going to increase the population”.

Just saying that he was going increase the population reveals the fact that it’s impossible to just implement different policies. When you are the manager of a business whose sales are in decline, if you say without thinking it through: “the sales are going to increase”, without saying how, nobody would believe you, would they? For me, the work of someone in politics is to act in such a way that you create a structure within which people are happy, even if the figures are low. These are difficult times, and, of course, I’m trying to increase the population, and even now when it’s temporarily in decline, I’m facing up to the problem.

Is there one issue you consider to be a priority today?

S. N. : The most important thing is the city’s sustainability, so that it doesn’t disappear. In reality, a city won’t just disappear like that. Japan is only a small island country compared to the rest of the world. It’s not the time to focus on the rivalry between Tokyo and Hokkaido. You must keep what’s best for the country at the forefront of you mind. The population is in decline, and one needs to think about sustainability. I think that’s the most important thing. Of course, one can dream, say to oneself that the population will increase, but the reality is that we’re seeing the opposite trend. So one needs to make sure that citizens can live well, even if the number of inhabitants declines. To think about how to make people happy, to create a system that supports a pleasant life… that’s what one must strive to achieve.

Are you undertaking any cultural projects? Is culture a determining factor in helping stabilise the population?

S. N. : Because it was made bankrupt, Yubari was the city that saw its budget slashed to lower levels than anywhere else in the country. As I came from Tokyo, I invited artists from there to Yubari. They told me: “When you want to create a work of art in Shibuya, you find all the neighbours on your back, complaining about the noise… In Yubari, the neighbours bring you things to eat, and even ask if they can help you”. They were very happy, they were able to make Yubari into a creative space where they could express themselves artistically. When times are hard, the arts can be very helpful in lifting people’s morale. Every year, Yubari hosts the only science-fiction film festival in the country. Day to day life is difficult, but once a year, during the film festival, we forget our problems, and we can watch hundreds of films from morning until night. You know that Angelina Jolie came to Yubari. Quentin Tarantino, too.

For many Japanese, Yubari is a city of nostalgia. There’s still an atmosphere redolent of the 1950s here. Isn’t it time to bring the city into the present?

S. N. : For me, there are some things you must protect, others you can get rid of. What one must preserve is the concept of ichizan ikka (one mountain, one family). People, whether related or not, worked together on the mountain, maybe even died there if there was a rock fall, some escaping gas or a fire … but, while clinking glasses they all became one family: “If I should die, I rely on you to take care of my family”. That’s what happened. That’s why we say “one mountain, one family”. That’s the culture of Yubari. In a large city, you don’t even know your nearest neighbour. It’s because life is easy, practical. You can live without helping one another. But that’s not the case here, you can’t live without mutual support. That the reason, even today, this idea of “one mountain, one family” remains crucial. But there are things that could be changed, for example, the state of mind that wants to return to the period when there were 100,000 inhabitants. One should instead think about how to make those who are still here happier. In order for that to happen, everyone must take a step forward, otherwise nothing will change. So there’s a feeling both of preservation and change, which needs to develop simultaneously. That’s why we’re talking to people and saying: “if you love your city, make an effort!”. The first time I heard the expression “one mountain, one family”, I thought it was beautiful. Over a period of a hundred years, 3,000 men lost their lives in the mines. Women had to raise their children on their own. It was hard, so people had to support one another. In Yubari, mining lasted until 1990, it’s not that long ago… People helped one another, they shared difficult and happy times. When the city was made bankrupt, we found ways together to get through that difficult time. There were two obstacles to surmount, the closure of the mines, and the city’s default in payments. The inhabitants succeeded in overcoming both these problems, so whatever happens, I think we’ll be able to pull through.

INTERVIEW BY O.N.

Leave a Reply