Maya (left), accompanied by her father, is proud of her Ainu origins.

Forced for a longtime to keep quiet about their origins, these indigenous people are fighting for their existence.

Not many people stop in Nibutani, a rural Hokkaido village two hours drive south-west of Sapporo. Truck drivers and motorcyclists pull up for a short stop at the gas station or the drive-in cafe, the only restaurant in town, en route to other destinations. The village is cut in half by a major state highway, and it spreads along the road, surrounded by mountains and forests. The road runs almost parallel to the Saru, a sacred river to the Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan who have lived here for centuries.

The ‘white people’, as they were called by lastcentury ethnographers for their Caucasian features, the Ainu are still little known outside Japan. Originally from the island of Hokkaido and Sakhalin, now part of Russia, they were colonised by the Japanese in the Meiji era. By the first half of the last century, they were almost completely assimilated, their religion and language banned, their land taken away. It’s estimated that today there are around 25,000 people of Ainu descent in Japan, mostly living in Hokkaido. However, this figure cannot be verified: many Ainu descendants prefer to conceal their background to avoid discrimination. Ethnic physical features are now less visible, often impossible to detect, after over a century of mixing with the Japanese.

Remembered by most for their picturesque tattooed lips and the bear ritual sacrifice, the Ainu today are still battling to be fully recognised. In the wake of being selected for the 2020 Olympics, they are raising their voices to achieve full acknowledgement at home and abroad, in a struggle against invisibility that has never halted. The Ainu achieved the official status of indigenous people of Japan only in 2008, after a history of forced assimilation that almost completely wiped out their society, language and culture. Today, individuals and groups across Japan are involved in the preservation and revitalisation of Ainu culture, such as reviving their language.

Nowadays, Nibutani and other main centres of Ainu culture in Hokkaido, like Shiraoi and Akan, bear little resemblance to the places as recorded by anthropologists in the last century. But traces of the past, tangible and intangible, visible and invisible, are still there. Tattoos and long beards are mostly gone, and people now drive jeeps, but they still climb mountains to gather wild plants, hunt deer and occasionally bear, according to the Ainu puri, the indigenous philosophy of daily life practices.

Monbetsu, from Biratori, is a thirty-something professional hunter. Wearing the fur of the bear he has shot and skinned himself, he drives his jeep up into the foggy mountains almost everyday at dawn to hunt deer. The pre-fab house he shares with his wife and two daughters is full of hunting trophies. Deer and bear skins and bones are turned into everyday objects, such as carpets and knives; deer skulls and horns decorate the walls.

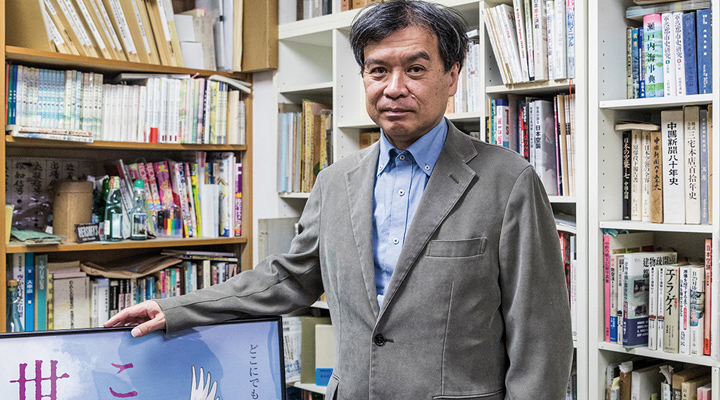

In the Ainu animistic religion, humans are not considered superior to other living beings and things. Plants, animals, objects and natural phenomena are kamuy, or incarnations of gods. Before a wild plant is taken or a trout caught, humans must thank the kamuy for providing them with food. Ainu elder Kaizawa Yukiko is called by everyone in Nibutani Okasan, “Mother”. She often walks up the mountains to gather edible plants such as kitopiro, the Ainu leek. All geared up with hiking boots, a knife and a bell to keep bears away, she will also peel bark off elm trees for her attush, a traditional form of weaving. The green prefab where she dyes and weaves the tree fibres, which hang from her workshop as though in a primordial forest, is also a gathering place for family and friends. For many years, Yukiko has been teaching Ainu puri to her 17-year-old granddaughter Maya. Maya is proud to be an Ainu. Unlike most people of previous generations, she has never experienced discrimination or bullying for being “different”. Many Ainu people, only a generation ago, concealed their origins, and only came out as Ainu in their 30s or 40s.

Maya’s mother is Ainu, while her father Kenji is not. Sekine Kenji had stopped off in Nibutani twenty years before while on a cross-country bike trip, and never left: he married an Ainu woman, and became so involved in the community that today his life is dedicated to reviving Ainu, a critically endangered language with no native speakers left. After becoming a fluent self-taught Ainu-speaker, he now teaches the language to the children in the village. He also runs educational radio shows in Ainu. Recovering their language remains one of the crucial issues for the Ainu people.

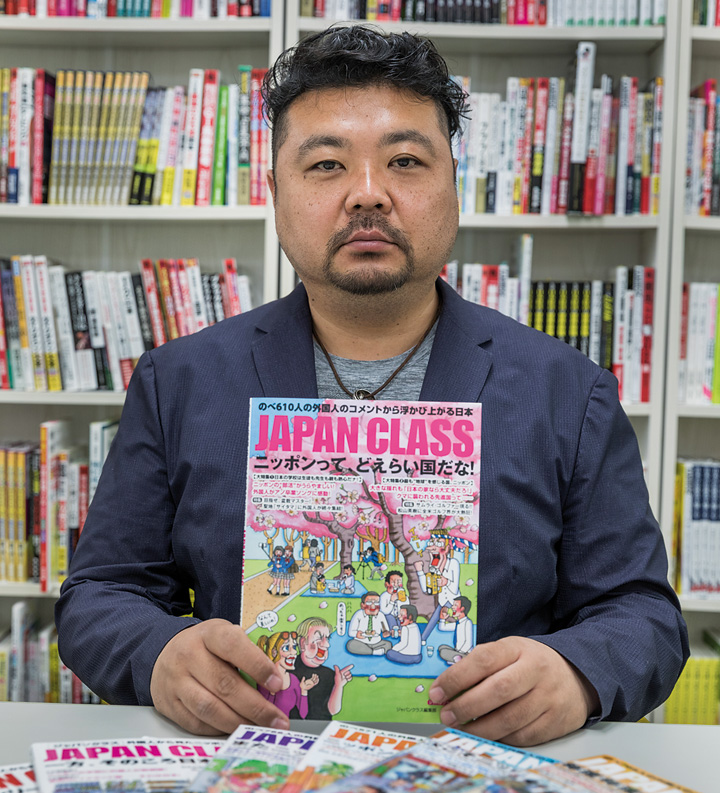

Museums in Hokkaido are perhaps the easiest way to encounter Ainu people and culture. Nibutani is home of two important museums of indigenous history in Japan, one of which was founded by activist Kayano Shigeru, the first Ainu to sit in the Japanese Diet. Shiraoi, not far from Sapporo, and Akan, a two-hour bus ride from Kushiro, are the most popular Ainu tourist sites. Here, indigenous- themed tourism was already booming by the 1950s. Shiraoi and Akan have reconstructed kotan, or Ainu villages. Inside the thatched homes called cise, Ainu employees perform traditional dances and songs, and carve souvenirs for tour groups from Japan and abroad. Porotokotan Ainu Museum in Shiraoi is undergoing development to become a national institution, and hopes to raise its visitor numbers to a million by 2020.

The cise, a traditional Ainu house built by Urakawa Haruzo in Chiba Prefecture, to the east of Tokyo.

For many Ainu, the tourism industry is the only way to pass on their culture. Some criticize these institutions for adulterating their own heritage to please tourists. Others like Kano Oki just prefer a different approach. He is one of the most interesting figures in the contemporary Ainu music scene. A skilled player of the traditional plucked instrument, a tonkori, he experiments freely with other forms of sound. Alone or with his band Oki Dub Ainu, he has recorded numerous albums, appeared on national TV and toured overseas.

His legacy at home has been to shape entire villages and communities across Hokkaido.“Whether or not you are Ainu, this village is an Ainu village. Those who live here can’t choose to be or not to be Ainu.” According to Kaizawa Maki, an Ainu woman from Nibutani, even the non- Ainu, or Wajin, naturally stick to the indigenous lifestyle. Many Wajin come to Hokkaido to learn and live this indigenous way of life. Jun, a Japanese man from Tokyo, moved to Nibutani and started a family. He, like many others, left the city in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. He dreamed of a new life, closer to nature, and found it in the Ainu way of life. Among the first Wajin to join the native community were the Takanos, who came to 1960s Nibutani to become skilled Ainu artisans. They integrated to such a degree that they were the last family to perform the ritual bear-killing in the village, the iomante, with the participation of the whole community. The iomante is a complex ritual, no longer practised. It involved the adoption and later the sacrifice of a bear cub. The bear was first raised as a family member: it was given a name and treated like one of the children. Before it grew too large, it would be sacrificed to ‘send its spirits back’ into the world of the gods. The bear would be killed with arrows, skinned and eaten. Its skull was then decorated and placed on a spear. The whole village of Nibutani participated in the sacrifice of Ponta-chan, Takanos’ pet bear. Ponta’s skull is now on display in one of Nibutani museums.

Nibutani, Shiraoi and Akan might be small and geographically isolated, but they are not only prominent sites of Ainu history and culture, they are also very well connected to the rest of the indigenous world. The Ainu across Japan all know each other and constantly dialogue, debate or even fight about cultural and political activism. They share their knowledge and activities through an extended network of social media, as well as through local events and initiatives. Some Ainu groups have reached out to other indigenous communities worldwide, organising cultural exchanges with Maori and Native Americans groups. There are no more boundaries: the small Ainu Kotan have become global villages.

LAURA LIVERANI

Leave a Reply