Tezuka Osamu and Mighty Atom at the Tezuka Productions office in Saitama.

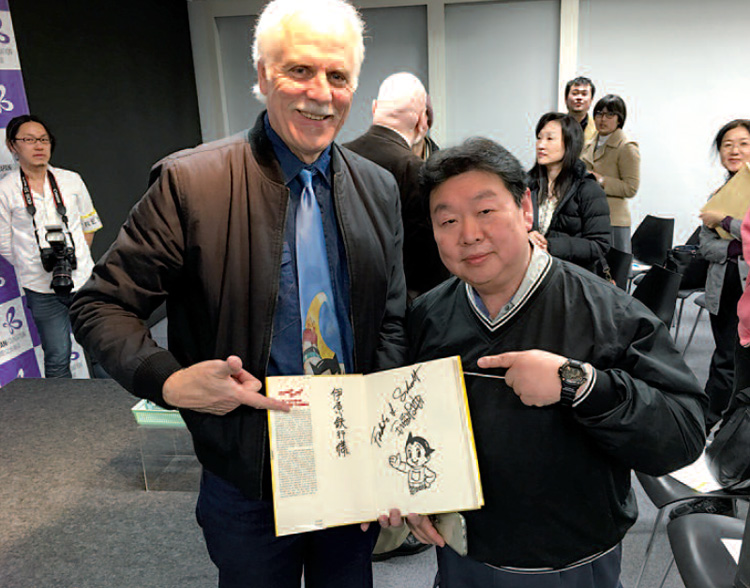

Frederik L. Schodt was one of the very few Westerners to become close friends with the mangaka.

Few people outside Japan have known Tezuka Osamu as well as Frederik L. Schodt. Not only did the veteran author and translator write the first English-language book about Japanese comics (Manga Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics, 1983) but he was Tezuka’s interpreter and personal friend. Most recently, Schodt translated Ban Toshio and Tezuka Productions’ massive manga biography of Tezuka, entitled The Tezuka Osamu Story: A Life in Manga and Anime. As Schodt told Zoom Japan, in the 1970s he was part of a group that wanted to translate and introduce manga to the western world. Their project led him to meeting Tezuka (by that time Schodt was already a great fan of his works). The meeting was life-changing for Schodt, who went on to work with Tezuka as his interpreter and consultant.

“In 1977, I began working as a professional translator. Around the same time, I joined three friends – Jared Cook, Sakamoto Shinji, and Ueda Midori – to form a group, called Dadakai, to translate manga,” Schodt says. “In Japan it was a fairly radical notion because most people then assumed foreigners would never be interested in what manga artists were doing. We were young and naive and started at the top, approaching Tezuka Osamu and a few other artists, asking them permission to translate their works.” Somehow the four friends’ naivety worked in their favour as Tezuka Productions invited them to discuss the matter. “We visited his office and Tezuka himself suddenly materialised while we were talking to his manager. He was very nice. He wanted to know why we were interested in manga. Anyway, we gave Tezuka Productions the first five volumes of Phoenix that we had translated… and they stored them away for 25 years until they were finally published in 2002 by US firm Viz Media. That’s how we got started. That was basically my first manga translation.”

That was also the beginning of Schodt’s long relationship with Tezuka. “It was a very memorable experience,” he says. “He was one of the most extraordinary people I’ve ever met in my life. I think he was a genius. As an interpreter, I’ve met a lot of famous people, but Tezuka really stands out. “I feel like I got to know him in a way most people didn’t. He was a fascinating person. I have to say that he made a huge impression on me. He was super productive, almost to the point of not being normal. He was always working, always coming up with new ideas while plotting various stories at the same time. He would be working on four, five stories at once, developing them in his head and getting them published in different weekly magazines. I’ve never seen anybody like him.”

One of the things that set Tezuka apart from other artists was his curiosity. Schodt remembers his wide-ranging interests. “He was extremely well read,” he says. “He knew about international comics and animation, of course, but he also read a lot of Russian, German, American, and British literature. He had seen all sorts of films, and remembered everything he saw and read. He had a near-photographic memory.

And let’s not forget he was a qualified medical doctor. At that time in Japan, it was very rare for people with that kind of education to become manga artists, because it was such a precarious life-style.” Schodt’s friendship with Tezuka was cemented during the artist’s several trips to America, when Schodt acted as his interpreter. “During those trips, while travelling from one event to the next, we used to talk all the time,” Schodt recalls. “We’d talk about anything: religion, ecology, you name it. He was like a sponge, always craving and absorbing information because he constantly needed new ideas for his stories. I remember at one point he was very interested in nuclear power because when he first created Atom, the robot had an atomic engine, but by the time I met him, nuclear energy had become a very controversial subject, even in Japan. So, when he created a new Atom anime series in 1980, he hit on the idea of making nuclear fusion the source of Atom’s power because it was supposed to be cleaner and safer.”

Frederik L. Schodt in Tokyo in 1993 for the publication of his essay dedicated to manga. The press

conference was organised with Tezuka Osamu.

Schodt’s long conversations with Tezuka might have been the highlight of their relationship, but he once found himself in trouble because of them. “We were supposed to fly from San Francisco to Canada,” he says, “and we got so absorbed in what we were talking about that we missed our flight. We were actually waiting in front of the boarding gate. Everyone else boarded, but we just stayed there. I felt so terrible for missing our flight, but he didn’t get mad at me, which was amazing. He was very kind to me. I know sometimes he got angry with his employees, but to me and to his fans he was always very generous.”

Though, at the time, most people in America and Europe didn’t know Tezuka’s name, many fans knew and loved Astro Boy. “Probably the average American who had seen Astro Boy wasn’t even aware that it was made in Japan. But Tezuka was great at interacting with all types of people whether they were intellectuals or children. And even though he didn’t speak English very well, he could always draw pictures. He would draw somebody’s portrait or one of his characters. Drawing was a kind of Esperanto for him.”

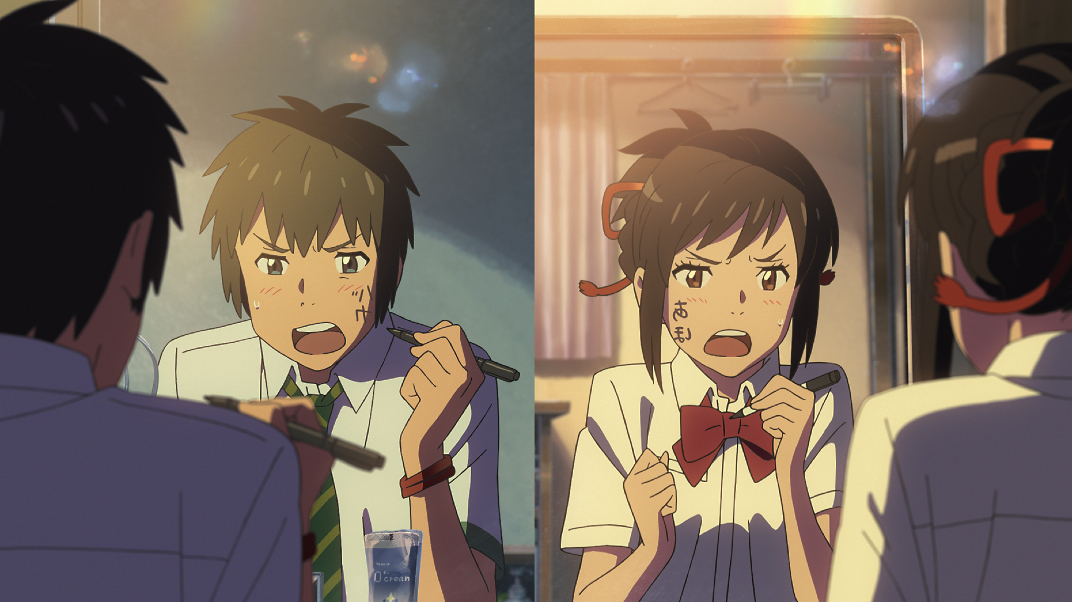

Speaking of Astro Boy, many foreign fans, especially in the past, knew this character through the anime version. However, according to Schodt, it’s in the original manga stories that one can truly appreciate the range of Tezuka’s interests and his storytelling genius. “You see, by the time you get to the anime, a lot of those stories are very watered down,” Schodt points out. “The original stories, which were first created in 1951-52, were actually very provocative. If you read them you’ll find some of them are really quite shocking. Later, a lot of the content was removed by Tezuka himself when he had to adapt his stories for the Japanese TV series broadcast in 1953. These same stories were further simplified for the foreign market. So, when I read the originals I was amazed by the way Tezuka was able to approach these complicated issues. Because the manga medium wasn’t so highly developed in the 50s, he was able to do just about anything he wanted. He had this very adult approach to exploring existential, philosophical, religious, and political issues, even though his manga were read by 11-12 year olds. He tackled such issues as artificial intelligence and machines – a lot of things we are still debating today.”

Schodt remembers Tezuka as a highly competitive person. “He had this innate desire to always be ahead of other artists,” he says. “However, when the gekiga movement started, there was a moment when he began to fall behind, so he made a conscious effort to demonstrate that he could compete at the same level as these younger artists who were dealing with more adult themes. There were many people in Japan who criticised him because his artwork always looked as though it was designed to appeal to younger people. In fact, he was never completely able to rid his artwork of that style, even when creating stories with very adult themes. He himself was very selfconscious about the fact that he had no formal art training.”

Although Schodt’s manga-related work has slowed down nowadays, his connection to Tezuka seems to be as strong as ever, as he found out when he translated The Tezuka Osamu Story. “I actually have a cameo role in the book,” he says, “which I didn’t realize until I was translating it. My name doesn’t appear, but it’s me in a few strips, and it’s based on a photograph.”

People often ask Schodt why he doesn’t write a biography of Tezuka. “The problem is that he was so prolific that trying to represent his life in just one book is an overwhelming task,” he says. “Ban Toshio, the author of the book I have just translated, actually did a fabulous job. He used to work as Tezuka’s “sub-chief assistant,” as they say in Japan, and was in charge of the night shift. As a result, he not only knew him well but could even draw in Tezuka’s style. Besides, he had access to all the archives of Tezuka Productions and the memories of employees and people who knew him.” The Tezuka Osamu Story is a manga full of information and biographical detail that explains both Tezuka’s work and who he was as a person. “Now, many people are interested in Cool Japan. If you trace back to the roots of manga and anime, you’ll always get back to Tezuka,” Schodt says. “Of course, he’s not the only person responsible for the international success of Japanese comics and animation, but he’s really the one who created the framework for the whole manga/anime industry.”

JEAN DEROME

Leave a Reply