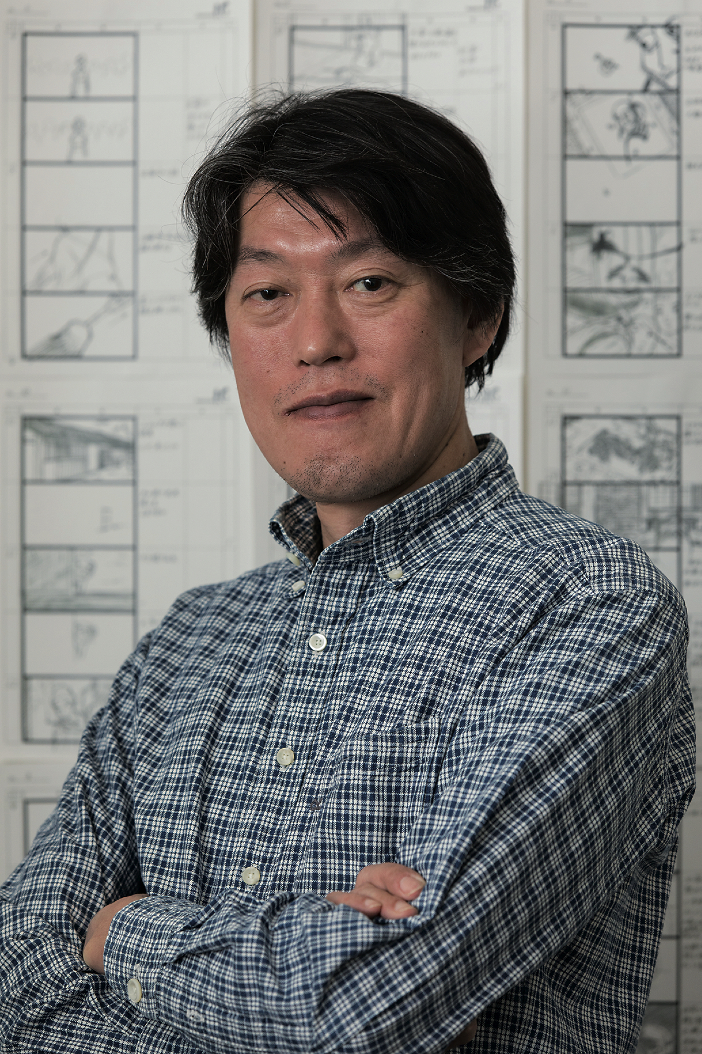

On a cold and cloudy October afternoon I paid a visit to Production I.G’s office in the Tokyo suburbs to meet anime director Hara Keiichi and talk about his films, his relationship with Tokyo and the future of animation in Japan.

Famous ukiyo-e artist Hokusai and his daughter O-Ei are the main characters in your latest film Miss Hokusai. However, I feel that in a sense the city of Tokyo itself (then called Edo) is the real protagonist of the story. What kind of place was it at the time?

HARA Keiichi: The film, like Sugiura’s manga, starts in 1814 when the Japanese were still living under a regime of sakoku (closed country, 1635-1866) meaning that exchanges of any kind with foreigners were severely restricted. This isolation, coupled with social and economic changes, led to the development of ukiyo (the floating world), a new kind of urban mass culture fuelled by the increasingly wealthy merchant class.

The typical culture and vibrant social environment of East Tokyo’s shitamachi (downtown) is rapidly disappearing. are you saddened by this?

H. K.: In a sense, you could say so. At the same time though, I think the typical Edokko’s (son of Edo) stubbornness and obstinacy haven’t completely disappeared.

By the way, in a previous interview you’ve said that you’re quite lazy. Is that true?

H. K.: Yes, I’m not a hard worker (laughs). I’m a little bit like the old Edokko — I only work when I feel like working. Of course, making anime can be a very high-pressure environment, and there are times when you have to focus very hard on the job in hand. In that case, there’s no time for lazing around.

You compared yourself to an Edokko, but you were actually born in Gunma Prefecture and moved to Tokyo at the age of 20. What’s your relationship with this city? Do you like it?

H.K.: Yes, I quite like it. Even as a child, I used to visit Tokyo with my family. I was always very excited every time we made the trip. The train we used to take arrived in Asakusa, so that’s a place I’ve known quite well for many years. Even when I entered vocational school, I commuted to Tokyo every day for the first year, because it’s actually not that far from Gunma. It takes about two hours one way, which for the Japanese is not an awful lot of time. Only in the second year did I move to Tokyo and rent an apartment.

While Miss Hokusai is for the most part a realistic story, Sugiura’s Edo – as she portrayed it in Sarusuberi – is a city full of supernatural phenomena. Is that the reason why you included them in your film?

H. K.: Yes, personally I’m not particularly interested in those phenomena, but I wanted my film to be faithful to her manga’s original spirit. Sugiura’s story features many such strange happenings. It portrays reality, but at the same time it has a visionary feel. It touches on various aspects of life, but the supernatural is always lurking behind the thin veil of reality. Sugiura rendered these phenomena beautifully on the page, and I found them very charming and fascinating. Apparently Sugiura could actually see these spirits since she was a child. I don’t have this faculty, but I do believe in such things myself. I think a comparatively high number of people in Japan believe in the supernatural, reincarnation and what we call “ano yo” (the netherworld).

If you were to be reborn, would you still like to be an animator?

H. K.: Ha ha! Yes, I think so. I think I’m really suited for this job.

You graduated from Tokyo Designer Gakuin where you studied art. When did you decide that you wanted to work in animation?

H. K.: When I was in high school, I had to decide what I wanted to do with my life. I had an artistic inclination and really hated office work, so I decided to go to art college. Unfortunately I lacked both the strong artistic talent and good enough grades to go to university. Then, one day, I was in a bookshop and found information on a vocational school that had an animation department. The word “animation” made a strong impression on me. Until then, I had loved manga and anime of course, but I had never imagined I could make a job out of them. It was sort of an epiphany. Something clicked in my head and I knew I could pursue that career. When I finally entered Designer Gakuin I was surprised by how many otaku were there in my class. Everybody was very skilled at drawing and they knew all the names of manga and anime artists I had never heard of. I thought I was no match for them and would never manage to become an animator. But I really love films, so I decided to become a movie director instead.

H. K.: When I was a kid, I was mainly into gag manga and I loved Fujiko F. Fujio and Akatsuka Fujio. Fujiko F. sensei in particular, has had a lasting influence on my work. He mainly wrote kids’ stories but they could be enjoyed by adults too. I don’t think I’ve ever openly decided to copy him or follow his style, but I’m pretty sure I’ve unconsciously absorbed his ideas.

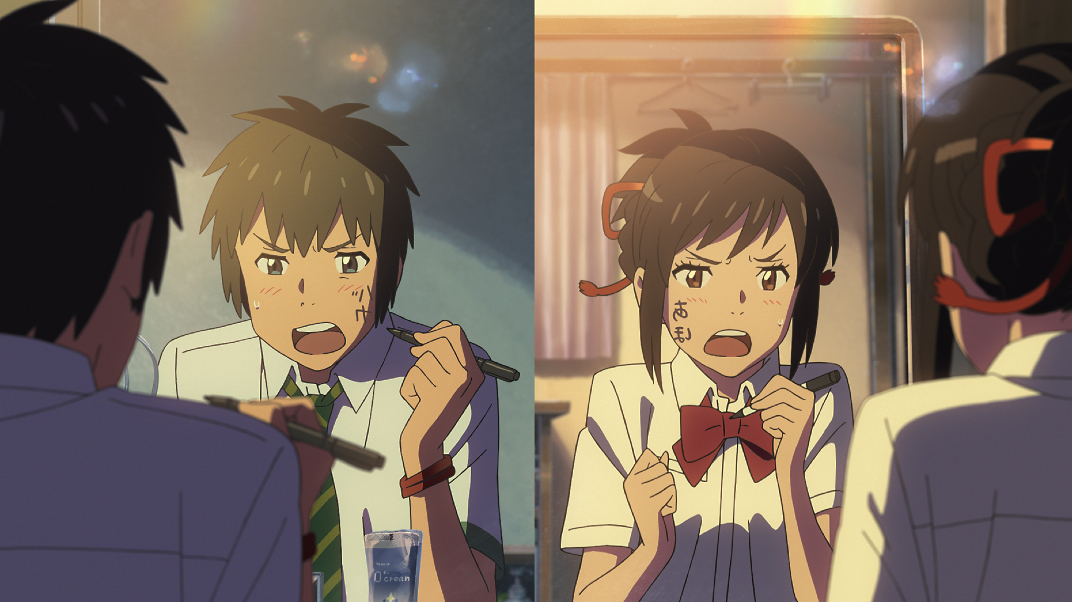

Speaking of Fujiko F. Fujio, recently you’ve become famous for such original films as Colorful and Miss Hokusai, but at the beginning of your career you worked for several years on TV series like Doraemon and Obake no QTaro, which Fujiko F. authored together with Fujiko Fujio a. What was it like working for TV and how does it compare to making original feature films?

H.K.: Well, ever since I joined Shinei Animation in my early 20s, I aspired to make feature films. I think that’s everybody’s aspiration, but only a few chosen people actually get to do it. As I said, I’ve always loved movies and the magic of watching a film on a big screen. So I consider myself lucky for having been given a chance to do the same and make something that other people could enjoy. In my particular case, comparing TV work and feature films also means comparing two different eras. Nowadays we live in the Internet age. Everything is saved on DVD or other newer recording systems, and with so many websites and social networks it’s very easy to gauge people’s reactions to what we do, but when I started there was nothing like this. Once an episode aired on TV, it was gone. The most you could get was a review in one of the few magazines devoted to animation. So we kept churning out one episode after another, just focusing on what we were going to do next. But with films it’s different. You actually have a 35mm copy that can be preserved and watched again and again. As an anime maker, that was probably the biggest difference between TV and film work. Then, of course, there is the matter of creative freedom. When you make your own original story you have a chance to try things that you could never do otherwise.

You have been making anime for about 30 years now. How has your approach to filmmaking changed through the years?

H.K.: I worked at Shinei Animation for about 25 years. Even though I directed many films, I was a simple employee. Shinei focuses on children’s animation and in the beginning I very rarely got a chance to put forward my own ideas. I only managed to establish myself in the company later, and was finally given a chance to do whatever I wanted. Eventually I opted to go freelance so that I could have complete control of my work.

Compared to the past, levels of censorship seem to have increased, even in the animation industry. Did you have any problems when making Miss Hokusai or Colorful (a film that deals with suicide, teenage prostitution and adultery)?

H. K.: In Japan, as in other countries, we have a rating system. In Miss Hokusai there are a couple of scenes that could have earned the film a PG12 rating, but luckily the Board of Film Classification found nothing bad with the story. Colorful, on the other hand, was more problematic because of the teenage prostitution issue. The distributor was very worried about this, so I proposed changing a scene so that the girl doesn’t say how much money she wants, but shows it with her fingers. For me this is even more vulgar in a way, but somehow the censors were satisfied with the change and in the end the film was rated G. Anyway, this funny episode aside, I’m really against this form of censorship. While I was growing up, unsettling and violent scenes in anime were the norm. I don’t agree with censoring death or other difficult issues. After all, they’re part of our world. Even children should know that not everything in life is beautiful and pure.

INTERVIEW BY JEAN DEROME

Leave a Reply