The last grand master of traditional tattooing, Horiyoshi III recalls his long life in the profession.

It is 9 a.m., and Hanasakicho is still asleep. At night Yokohama’s historical harbour-side neighbourhood is alive with lots of small bars and cafes, some old karaoke bars and a few jazz clubs, but on a mellow Saturday morning everything is closed. It is so quiet that one can almost hear the buzzing sound of a tattoo machine in a second-floor apartment. Inside, Horiyoshi III – arguably Japan’s most famous living tattooist – is already in full swing. The old irezumi master is 70, white haired and needs glasses to do his job, but he is still at the top of his game. I sit next to him on the tatami mat while he is busy inking cherry blossoms on the back of his young client.

Born Nakano Yoshihito in 1946, Horiyoshi III has lived in Yokohama since he became an apprentice at the age of 25. “I grew up in Shizuoka Prefecture, left school after finishing junior high and began to work as a welder”, he says. “In Japan, especially at that time, it was almost impossible to see tattooed people in the street, but many guys who worked with me in the shipyard had tattoos. I found them extremely fascinating, so I began to tattoo myself straight away, using needles tied to a disposable chopstick”.

Tattoos in Japan are traditionally associated with the underworld, and it was after watching a yakuza movie that the future tattoo master decided he wanted to become a professional horishi (tattooist). “I was 20 or 21 at the time and was getting deeper and deeper into irezumi culture. The main character in the movie had this beautiful tattoo on his back. It was after watching that film that I decided I wanted to make tattoos for a living”, he says.

In the late 1960s tattooing was very much part of underground culture, and finding a way in was quite difficult, but the young tattoo lover heard about Horiyoshi I, a popular tattoo master who worked in Yokohama, and wrote him a few letters asking to become his deshi (apprentice). “He never wrote back,” he says, “so I decided to visit him. The sensei was already training his son – who would become Horiyoshi II – but luckily he took me in anyway”. The young deshi left his job and moved into his sensei’s studio where he worked full time, and even slept there after work. “I still remember how he bought me a new futon. I was really moved by his kindness”, he says. “I became part of his family. I only earned a little, but his wife would cook for me and he would gave me cigarettes. I never had to worry about practical things. In return, I decided to devote my life to my master and his family. That’s what a real deshi is supposed to do. You are loyal to your sensei, always show your gratitude and never betray his faith in you. You never complain, no matter what happens. I remember once – it was a Sunday – he gave me the day off, so I went to the movies. But when I came back he scolded me. Where the hell were you, he said. A client came and you were nowhere to be found. I wanted to protest, but of course I didn’t. You never talk back to your master. You just take it on the chin and apologize”.

Horiyoshi III still remembers with a smile the somewhat awkward relationship he had with his sensei. “As a teacher he was very old-fashioned, in other words, he never taught me anything”, he says. “He never said do it this way or that way. My sensei would look at my work – that I’d been practising on my own – and murmur “mmm”. He never said well done or this is a piece of crap. He would just say “mmm” and I had to figure out what he meant, always striving to do my best. And then one day he just said, tomorrow you’re starting work on this client. That’s when I realized I had finally made it. And to me, that’s the coolest way to deal with these things. You don’t need to use too many words. That’s the traditional Japanese way”.

After 45 years Horiyoshi III is still trying to accomplish the perfect irezumi. “I used to be quite selfindulgent,” he says. “I couldn’t understand why someone like my sensei kept practising and studying even after becoming a well-respected tattooist. Only later I realized that a tattooist, like any other craftsman, is supposed to turn his craft into a lifelong quest, and in the process he can learn many life lessons. For example, in order to succeed as a tattooist you obviously have to be good at drawing, otherwise you can’t master the outlining of the tattoo. And outlining affects the next step in tattooing, which is shading. Only after the outline and shading are complete can you apply colour. Now, you can compare these steps to life itself. The outline, for example, is the same as planning your life and making clear what you want to achieve. Every line you draw is like a day in your life, and every single day counts. Tattooing is exactly the same, and the more you practise the better you get. Not only that, through knowledge you acquire wisdom”.

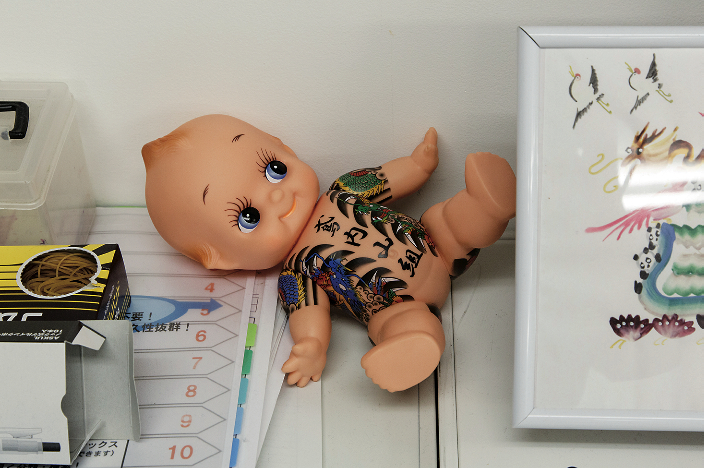

Horiyoshi III has finished inking the flowers that decorate his client’s shoulders. I ask him how he chooses the images for each client. “For me the most interesting subjects are myths and legends. A realistic portrait of a real person doesn’t really work unless you add a touch of fantasy and draw them as a legend. Having said this, I always start by asking what images my clients would like to get tattooed. This man, for example, requested a dragon and snake combination as his central motif (shudai). Flowers, such as cherry blossoms and peonies, are also very popular. In this case we’ve opted for cherry blossoms. Once we have agreed on the motif and background it’s up to me to arrange all the elements into a cohesive design. After all, tattooing is a collaboration between the tattooist and his client, and it’s based on mutual trust. The client offers his body as a canvas for the tattooist to create his work. He also has to understand that in traditional Japanese irezumi there are certain rules to be followed, and one is not free to do whatever he wants”.

Speaking of style and images, I ask Horiyoshi what makes Japanese irezumi so unique. “To put it simply, all irezumi have a specific meaning,” he says. “They often come from Japanese myths and legends, ancient history and religion. Also, in Japan, we have four distinct seasons, and each tattoo works best with a particular seasonal setting. We’re always careful to include these seasonal references in our work. For example, if it’s a spring-related design we usually include cherry blossoms, while maple leaves signify an autumn theme. The problem is that nowadays many youngsters don’t know these old stories, so they will sometimes put together a disparate array of unrelated images. To me, it just looks wrong; there’s no harmony, no unifying theme. Maybe each single image has its own meaning, but the overall story is missing. I don’t mean to say that putting a collection of one-point unrelated tattoos on your body is wrong. In principle there is no right or wrong when it comes to tattoos. It’s just that I was trained in a certain way and, personally, I prefer the traditional approach”.

Tattoos have become more and more popular, especially among young people, but Horiyoshi is not very happy about mainstream society’s gradual acceptance of the medium. “Now many young girls get a tattoo on their arm so they can openly show it around, even in the street. But I don’t like that; it runs against the traditional aesthetic of tattoos. I don’t mean to say that tattoos are some sort of outlaw art, but I believe they are still part of underground culture and are not meant to be seen by everyone. That’s what makes them so interesting”.

Jean Derome

Leave a Reply