Though it is more accepted abroad, the practice of tattooing is still challenged by the Japanese authorities.

They’re all around us. They live in our cities, work with us and teach our children. They are people with tattoos and, in Japan at least, most of them are very careful to hide their secret and keep their inked skin covered. One of the most misunderstood forms of art and body modification, even today tattooing (known in Japanese as “irezumi”, literally “inserted ink”) is equally revered and reviled around the world. Especially in Japan the profession of tattooing is undertaken in a legally grey area, and practitioners are constantly at risk of being fined, arrested and having their businesses shut down by the police. In the last few years Osaka Prefecture has been the main battlefield between tattoo artists and the authorities, mainly thanks to right-wing Osaka governor Hashimoto Toru who, among other things, conducted a controversial poll of civil servants in 2012, requiring anyone with a tattoo to disclose that fact to the authorities. Hashimoto stated that civil servants were not entitled to either personal privacy or human rights and suggested that those with tattoos would have to remove them or resign (the Osaka District Court later ruled that Hashimoto’s order was illegal and constituted an invasion of privacy).

To be sure, for the last 150 years Japanese tattooists and tattoo fans have had a hard time pursuing their passion, although the history of body modification in Japan is much older than this, and in the distant past the popular perception of tattooing was far from negative. People used to get their skin tattooed (or scarified) as far back as the Jomon Period (c.12,000 B.C. to c.300 B.C.), as shown by the markings that were found on the clay figurines from that time. Later, according to Chinese records from the Third Century, many Japanese males had heavy tattoos on their faces and bodies, either to emphasize social differences or to protect themselves against hazards at work (e.g. fire fighters, coal miners) and evil spirits (such as in the case of Ainu women in the northern island of Hokkaido). In matriarchal Okinawan society, where many women had their hands inked both as a sign of beauty and as talismans, tattoos were connected to female shamanism.

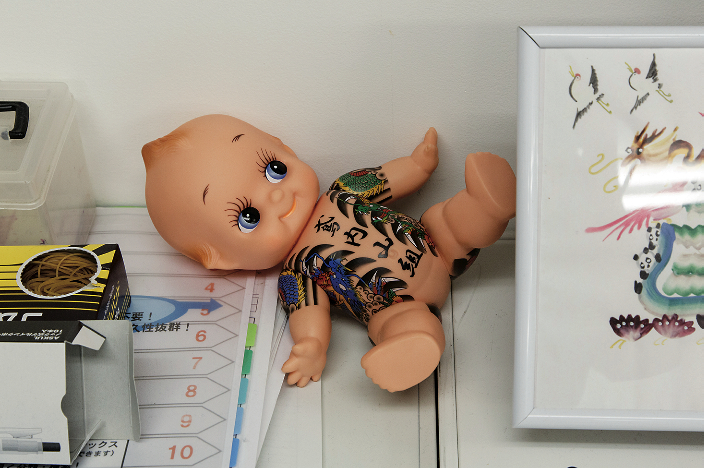

Today, on the other hand, even though things are changing, many people in Japan (and many other Asian countries) still have a very negative opinion about tattoos. Particularly in Japan, where people prize an unblemished skin, they are seen as dirty (according to Confucianism it is disrespectful to modify your body), but the real downfall of the tattoo has been its connection to criminals. In the past thieves and con men were tattooed on their arms and even their foreheads as a way to shame them and make them stand out. More recently, in the 1960s and 70s, the growing popularity of yakuza films contributed to the bad reputation of tattoos, with the films’ violent anti-heroes sporting heavilyinked bodies. Even today the association between tattoos and gangsters remains very strong in the minds of many people, despite the fact that in the past two decades more and more yakuza have been unwilling to be tattooed in order to keep a low profile amid an ongoing police crackdown on organized crime. You only have to check one of the many tattoo studios around Japan to see how diverse the clientele has become, ranging from salarymen and rock musicians to shop clerks and foreign tourists. Ironically, for a long time – especially during the Edo Period (1603-1867) – tattoos had a very close relationship with kabuki and ukiyo-e (woodblock prints), as kabuki plays often featured tattooed characters who were then portrayed by woodblock artists. But while ukiyo-e, and above all kabuki, have managed to overcome their bad reputation and lowbrow origins, and are today rated among the best examples of traditional Japanese art, tattoos have remained unacceptable in mainstream society.

That Japanese tattoos have not disappeared into the deep underground for good is, in part, thanks to foreign fans. Western travellers have been fascinated with irezumi since they first encountered them more than 150 years ago. It probably started with tattoo-loving sailors wanting the same amazing images they could see in the streets of Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki, but this interest in local skin art quickly spread to European aristocrats, including British Prince Alfred (one of Queen Victoria’s sons), Prince George (the future George V), Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Nicholas II, Russia’s last Tsar. Later, in 1948, irezumi became so popular with the occupying GIs that General Douglas MacArthur lifted the ban on tattooing that had made the practice illegal since 1872.

Even today it is interesting to see how differently tattoos are presented in Japan and abroad. Two years ago, for instance, the prestigious Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles devoted the largest-ever exhibition dedicated to irezumi – a six-month show featuring lectures, live tattooing and life-size photographs of Japanese tattoos. In contrast to this and other successful international events, the only tattoo-related exhibition you will find in Japan is the Yokohama Tattoo Museum, a cramped, rundown space which was opened in 2000 by veteran tattooist Horiyoshi III to house his personal collection. Though the exhibits include some rare artifacts, and are worth a look for hardcore fans, this dusty place is anything but a museum, and is the ultimate proof of Japanese people’s lack of interest in tattooing.

There is more than a simple lack of respect though, tattooing has recently come under attack from the authorities, particularly after the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare passed a new Medical Practitioner’s Law in 2001, stating that “the act of using a needle to administer ink” must be considered a form of “treatment” and can be only done by someone with a medical licence. The aforementioned arrests and other recent incidents (in 2015 Osaka’s biggest tattoo convention, the Ink Festival, was suddenly cancelled a week before it was to be held) have put a strain upon the local tattoo community, and many tattooists now prefer to leave the country and work in Europe and the US where they find a relatively more open environment (today in the US approximately one-fifth of the population is inked).

However, tattooists have been fighting back. Last year, for instance, Osaka-based Masuda Taiki appealed an order by a summary court in Osaka to pay a fine of 300,000 yen for violating the Medical Practitioners’ Law. While his case is still on trial, Masuda’s stance has gathered a lot of support and a Save Tattooing in Japan campaign is currently trying to gather 100,000 signatures while pointing out that tattooists always follow rigorous sanitation standards using only disposable needles and ink containers, and wearing gloves and a face mask during work.

The good news for the Japanese tattoo community is that, amid the constant struggles, more and more people are actually getting inked and choosing tattooing as a viable profession. In fact there are currently an estimated 3,000 tattoo artists working in Japan, compared to approximately 200 in 1990. The government has also partially accepted the idea that tattooed people is not as scary as they may look. This year the Japan Tourism Agency has asked hot spring and public bath operators to allow foreign tourists with tattoos into their facilities. After all – so the reasoning goes – they come from different cultural backgrounds and probably wear tattoos for fashion, religious or other reasons. Besides, it would be bad to ban tattooed foreigners while the government is trying its best to attract as many overseas tourists to Japan as possible. Unfortunately the Japanese people themselves are still not allowed to show off their tattoos in public. Sorry folks, maybe sometime soon.

JEAN DEROME

![No51 [MEMORY] A writer who cannot forget](https://www.zoomjapan.info/wp/wp-content/uploads/focus02.png)

Leave a Reply