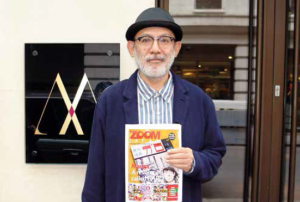

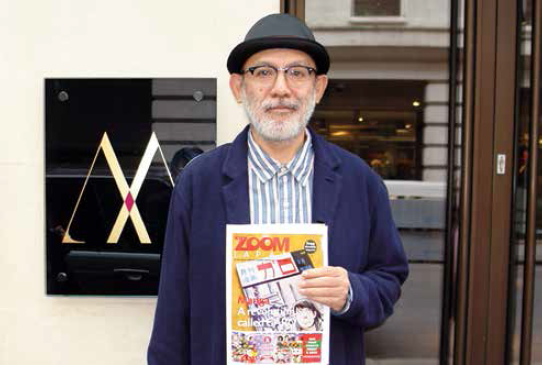

Adapting a novel by Akio Fukamachi, the director offers a very strong film full of violence. He explains his choice.

Have you been to the U.K. before?

Nakashima Tetsuya : No, this is my first time here.

I see, so what kind of impression did it leave on you?

N. T. : I’ve only just arrived, so the only thing I have noticed is the fact that the weather is nasty, but I will be doing some exploring during my stay. However, the first screening took place yesterday and it was very interesting and a great pleasure for me to hear how people here were trying to understand the film on such a deep level. When it was released in Japan the viewers mainly just noticed the violence – especially with the younger audiences that my movies tend to attract-, and the only comments I heard were something like the film is “too gross” or “too erotic”. I don’t usually get to hear any opinions beyond that, but with the audience present at yesterday’s screening I felt that they were trying to understand the context of a profound humanity that I attempt to convey. They were also very direct with their opinions and how they felt about the production, which I was thrilled about.

British people have this unique depth of emotion, don’t they? it must have been very helpful that they have solidity to the ideas that they communicate?

N. T. : It was interesting when they pointed out elements that I had never even thought about before.

That must have been useful to hear so many subjective interpretations?

N. T. : Yes, it certainly was.

What were your reasons for wanting to turn Fukamachi Akio’s novel into a film?

N. T. : I literally just took it in my hand at a book shop one day and started reading it. I was drawn to the main character of Fujishima, who is played by Yakusho Koji in the film, and I found his violent personality very intriguing. To me, it seemed like he uses that violence as a primary tool for communication. To put it simply, it doesn’t mean that he is a through and through outlaw and can live life on his own just because he is such a destructive character; he is actually quite a lonely person. He has a desire to form connections and relationships with people, but when he tries to communicate words are replaced by physical violence. Deep down he wants to make it work with his wife and his daughter, and he doesn’t want to be alone. Yet he ends up raping the wife and strangling the daughter. So he wants to reach out to them, but he just does not know how to do so. I found this very captivating when I was reading the original novel. The world is full of rules and principles, so people like Fujishima often end up ‘dropping out’ of human society, but in his case it felt as though he was only expressing an animal-like instinct, and ultimately we are all animals after all. People like him get labelled as “hooligans” or as worthless people, but the impression that I got was that maybe how he is acting is like when babies react by slapping things – the natural state of a human being before rules and ‘norms’ get bashed into their minds. Although the problem is that his way of communicating can only be achieved through brutality, so it does mean that it is impossible for him to interact with others. This is a very tragic thing for a human being, but at the same time I felt like it is also quite a comic element. So I found the character Fujishima to be both tragic and comical simultaneously, which made me think that maybe I can produce quite a thought-provoking movie if I make a film about this person.

Are you fascinated by characters that general audiences will find it difficult to understand?

N. T. : Most of my films do indeed have main characters who have been pushed away from human society, and I am very interested in such people. I feel like it is all part of enjoying a film when it is difficult to sympathise with a character, although I do hear complaints when my films come out that some of the audience are finding it impossible to feel sympathy. However, it is my opinion that there is not much point in making a film in which it is easy to sympathise with all of the characters. Everyone produces movies like that, so audiences come to expect it and it is very easy just to do that. When constructing the character of Fujishima, it would have been possible to portray glimpses of his good aspects and his timidity as well, and thus lead to audiences being able to sympathise with him. However, I strongly felt that I wanted to illustrate nothing but his flaws, as a rejection of the current Japanese film scene. I thought that there would be no point in me doing the same as everyone else. With the way Fujishima is portrayed in this film, most people will probably just think something like “I don’t like this character”, but if at least one person can feel intrigued and think about the more surprising aspects that people have to their personalities then I will feel that there was a point in making a movie like this.

What kind of message are you trying to convey with this film?

N. T. : I don’t really want to say what exactly the theme is supposed to be, because it is very much up to the audience’s interpretations. But you can see something of it in the way that Fujishima spits out aggressive dialogue like “I’ll beat you to death” or when he swears. He only speaks in this kind of aggressive language, but the truth of his personality and character screams out through those words. For example, in The World of Kanako people are all smiling and speaking kindly to each other, but there is definitely something cruel and dark hidden behind their words. I want the audience to realise that the words being spoken and the true emotions behind them are two different entities. The film begins with Fujishima saying “I’ll beat you to death” and also ends with exactly the same words. I hope that the impact of the first “I’ll beat you to death” on the audience will be very different to that made by the last “I’ll beat you to death”. There is a similar kind of dissonance with the daughter, Kanako, as well. With her words of “I love you”, she keeps on throwing people into hell. In both the real world and in the relationship of films and their audiences, people believe words a bit too much. They simply take in the words expressed at face value. It would be great if my audiences could feel at least a tiny bit that everyone in The World of Kanako is actually saying the complete opposite to how they truly feel.

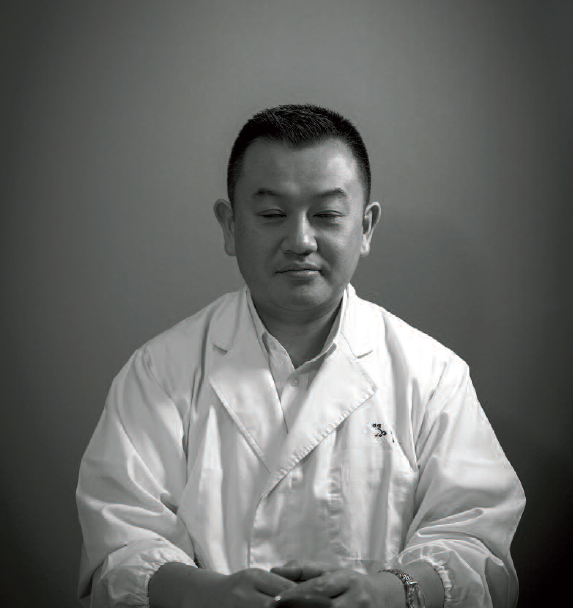

Tell me more about the casting of Yakusho Koji and Komatsu Nana.

N. T. : When creating the character of Fujishima with Mr. Yakusho, there are tragic and scary, violent scenes, as well as the partially comical tone to get right. I have seen many actors in my life, and there are plenty who can act stupid and frightening and then switch rapidly to the absurd, changing the expressions really quickly, but the only person I have ever seen who can switch their expressions in one or two seconds, or even act out two different emotions at the same time is Yakusho Koji. So I definitely wanted him as Fujishima and that was the decision made.

The last time you worked with Mr. Yakusho was at the production of ‘Paco and the Magical Book’, wasn’t it?

N: Yes it was. In the first half of ‘Paco and the Magical Book’, the character he played was just a horrible man, but in the last half he does go on to become a nice guy. This is just my personal opinion, but I prefer Mr. Yakusho’s acting when he is playing a character that is hated by everybody to when he is playing a good guy! I always wanted to illustrate delicate human emotions through his acting and make it into a film.

Tell me your opinion on the director Quentin Tarantino.

N. T. : I love his films. They are fascinating, plus he emerged as a new star when my generation was a bit younger. There are many Japanese film directors who were inspired by Tarantino right, such as Fukasaku Kinji? Before starting shooting on ‘The World of Kanako, rather than watching Tarantino’s own films over again, I looked at a few of the films that he liked himself, such as the Japanese Toei B movies from a long time ago. This was mainly for the character-building of Fujishima. I wanted the ‘three years ago’ setting to feel like the old Showa era outlaw movies, so I did look at similar films that I used to love as a child, like the old yakuza movies. They all share a similar atmosphere, so I feel something congenial in him. Of course I highly respect him as a director too.

Finally, please could you leave a message for the Zoom Japan readers?

N. T. : I would like the readers to watch my film with an open and natural mind, free of preconceptions. I don’t think I make movies that have an emotional resonance that only Japanese people can understand, so if they do find it difficult to grasp The World of Kanako, that won’t be the reason why! I would love to hear comments and opinions, based on how they feel about the human image that I tried to depict in the film.

Interview by Yoshiki Ban