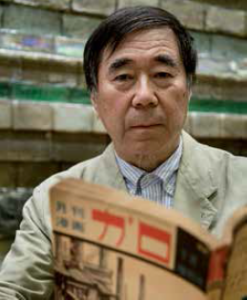

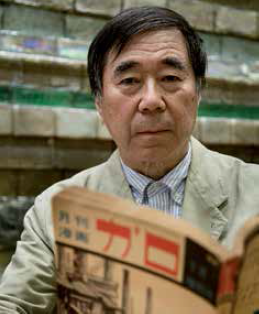

As a great lover of manga, the writer Kawamoto Saburo shares with us his admiration for this legendary magazine.

As far back as he can remember, Kawamoto Saburo has always loved manga. Now 70 years old, the writer is a famous literary and film critic; he is also a compulsive manga reader and an astute observer of this medium. Two years ago, he finally published a book about his favourite authors, some of whom helped make the reputation of Garo.

Where does the name Garo come from? I read somewhere that the founders were inspired by an American gangster called Joe Gallo when choosing the title.

Kawamoto Saburo : It’s possible, but you need to know that Garo was also the name of a character created by Shirato Sanpei. He’s one of Japan’s most famous manga writers, whose reputation is as great as Tezuka Osamu. Between 1959 and 1962, he created a series called Ninja bugeicho: Kagemaru-den [Ninja Martial Arts Chronicle: The Legend of Kagemaru], in which a character named Garo appears. Shirato Sanpei also played a major role in launching the magazine.

Garo first appeared in 1964. Do you think this monthly magazine represented some sort of revolution in the history of manga?

K. S. : Absolutely. Then again, its creation was the logical outcome to the changes manga had undergone since the end of World War Two. This transformation began in 1959, when the two major publishing houses, Shogakukan and Kodansha, founded Shonen Sunday and Shonen Magazine. Both were intended for the general public, but they inspired a new wave of young non-conformist artists. The rise in manga book rentals (kashi-hon) also played an important part. Back then people were used to renting books, just as we do DVDs nowadays. The shops that loaned these books, often very small, were mostly situated in the suburbs or small towns. You could usually find lots of alternative publications that were not on sale in traditional bookshops.

How did Garo revolutionize manga?

K. S. : Garo’s succes has inspired many imitators. The most successful was COM, the monthly magazine launched by Tezuka Osamu in 1967. A few artists worked for both publications, although they didn’t share the same editorial philosophy. Tezuka was a humanist and his style was rather serious. Shirato’s stories depicted scenes of great violence, sometimes quite unbearable. His style was much darker. He would address issues such as poverty and social inequality, and his characters often lived on the margins of society. And besides, it was in Garo that mangaka like Tatsumi Yoshihiro was published for the first time. Garo’s approach was also different in the way that its stories were aimed at an adult or young adult audience, whereas other publications would primarily have younger children in mind. So one can make a clear distinction between children’s manga (jido manga), with their more positive messages and simple plots, and manga on loan in the shops, which were more in tune

with the underground scene.

Did you have high school and university students in mind when writing?

K. S. : In truth, most customers who borrowed books were young workers. At the time, only 40% of high-school students went to university. Most would start working as soon as they left highschool. Those were the core readers back in the 60s. I think they enjoyed the stories we told because they shared the same dreary lives as the manga characters, who were living on the margins of society. Of course, younger students also discovered these magazines. That’s what happened to me. In 1964, I was a young university student when I discovered Garo. I was blown away. It was the first time I’d seen anything like it.

What was your favourite manga?

K. S. : I immediately enjoyed, and still enjoy, the work of Tsuge Yoshiharu. Shirato’s stories, like Kamui-den, dealt with class struggle and peasant revolts. It resonated well with the student movement facing down the police in the streets to protest against the war in Vietnam. But I had a preference for Tsuge’s style. His characters were young artists, always ready to fight it out, living on the margins of society and who would take long trips across the country.

Like a Japanese equivalent of those American classics which take place “on the road”…

K. S. : Yes and no. Japan has a long tradition of amazing poets and artists, like Matsuo Basho or Taneda Santoka, who lived almost like hermits. In my opinion, Tsuge is similar. What captivated me the most was the choice of destinations. Instead of going to trendy places like Tokyo, Nara, or even Kamakura, they would head to out-of-the-way spas, small fishing villages or other unexpected places.

It was very different from the image Japan wanted to portray to the rest of the world.

K. S. : It couldn’t have been more different. In 1964, Tokyo was hosting the Olympic Games. For the government it was all about showing off the technological aspect of the country, especially the new high-speed train. Japan of old was being slowly replaced by a new model. However, there were manga like Tsuge’s, which showed the world that traditional Japan had not disappeared. You just needed to step to one side. Tsuge was fond of those forgotten places. You can really feel it when you read his stories. He displays a deep empathy for them.

Were those manga popular?

K.S. : You need to remember that Japanese society was living through great upheaval back then. Many young people, including myself, didn’t have a clue about how to behave in the face of these changes. Besides, as I have mentioned before, most readers were young workers with little education, who were known as Kin no tamago (Golden Eggs). They made up the core readership of Tusge’s manga. In 1968, when the famous Nejishiki [the Screw] appeared in Garo, Tsuge was 31. He was very shy and would avoid the limelight.

Garo’s golden age was between 1964 and 1971, but the monthly magazine continued to be published until 2002. How did its contents change?

K. S. : In the beginning, only 8,000 copies were distributed. This number increased ten-fold in the following seven years. In a way, Garo was a victim to its own success. A growing number of publications followed its lead before the larger editorial houses jumped on the bandwagon. The series Golgo 13, for example, was first published in 1978 by Shogakukan. It’s one of the longest running series and one of the most popular. Yet its style and content are very similar to what one could find to borrow in the shops. The larger editorial houses were not content with imitating Garo’s style; they tried to lure artists that had started out with Garo, offering them higher royalties. Slowly, alternative manga were swallowed up by mass culture. Garo lost its aura and its circulation dwindled to 20,000. I was one of those that left. I stopped reading Garo when Tsuge left the magazine in 1970. His work continued to be published, but at a much slower rate, before he finally stopped in 1987.

Why did he stop drawing manga? Couldn’t he make a living from it?

K. S. : As I said, he’s a very shy person who always had difficulty accepting his status as a best selling author. He wanted to stay in the shadows. The other reason that prompted him to retire was the way the manga industry evolved in the 1970s. Basically he was a free soul who had a very traditional approach to his art. He would draw when he felt ready and never got used to the frantic rhythm of weekly publications, nor did he get along with his assistants. You mentioned money. What is fascinating about Tsuge is that the less he drew, the more he earned. He still has many faithful followers, and his stories are regularly reprinted.

Interview by Jean Derome

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat