This year is the 60th anniversary of the release of Tokyo Story. Yamada Yoji drew inspiration from this major work.

This year is the 60th anniversary of the release of Tokyo Story. Yamada Yoji drew inspiration from this major work.

Directors Yamada Yoji and Watanabe Yutaka (Kinoshita Keisuke’s assistant) came to the Shochiku Studios in Ofuna in 1954, one year after Ozu directed his opus, Tokyo Story there. There were many famous directors there at that time, including Ozu himself as well as, Shibuya Minoru, Oba Hideo, Nakamura Noboru, Kawashima Yuzo, Kobayashi Masaki, and Nomura Yoshitaro. We had a lengthy discussion with the two men, who had been living at the studios in Ofuna during that period. They talked to us about Tokyo Story and Yamada’s new film, Tokyo Kazoku (Tokyo Family), a tribute to Ozu’s most famous work.

Watanabe Yutaka : I’d like to turn to Tokyo Kazoku straight away, in which I could see the “Ofuna style” even though those studios have closed. I don’t know if I’ve already said this but Oba Hideo once said that, “through Yamada Yoji’s amazing talent, we were able to rediscover this tradition”. He was right.

Yamada Yoji : Really, Oba said that? That was kind of him. Well, for this film, I have to admit that Ozu was a good model. (laughs)

W. Y. : Just because you’ve got a good model doesn’t mean that everything’s always going to go well. It’s difficult.

I’m curious, when did you start to think that Ozu’s film making was so good?

Y. Y. : I don’t really remember that well. Maybe in the mid-80’s, when I was filming Otoko wa tsurai yo [It’s Tough Being a Man]. I had been told at a film festival abroad that my films were influenced by Ozu Yasujiro.

But since there were a lot of people then who thought that Japanese cinema was entirely Ozu, I thought it was just a throwaway remark. Basically, I was being told that my films were like those of the director who I least wanted to take after! (laughs) When I was young, I found Ozu’s films really boring.

W. Y. : I did too. I started thinking highly of his films when I was about 50 years old.

Y. Y. : Today Tokyo Story is considered to be the best film in the world, that’s really something.

W. Y. : People say that the first time Ozu received rave reviews from a British critic, his cameraman Yuharu Atsuta reported he said: “That’s it, the white man finally understands my films.” (laughs) “The white man,” that’s really an expression from before the war. Ozu served as a soldier on the Chinese front and after the defeat he was held prisoner in Singapore. He certainly must have all sorts of memories.

Y. Y. :He probably said that out of embarrassment. I always thought that Ozu’s films could only be understood by the Japanese, whereas I can see how Kurosawa Akira’s could be appreciated abroad. Actually, when a film is good, it can be appreciated by everyone.

W. Y. : The theme Ozu constantly described, the great emotion of life, is undoubtedly universal.

Y. Y. :When you’re young, it’s something you don’t realise. That’s why I considered his works as simple, petit-bourgeois films. They don’t often have anything do to with the difficulties of everyday life. At that time, it was still difficult for the Japanese to find enough to eat. When I was still in school, I’d spread margarine on a bit of bread that I ate with a glass of water, and that was all, that was my daily ration. I was so happy when I was able fill my stomach with a big bowl of rice and breaded pork! While everyone was going hungry the films were talking about eating vegetable dumplings and seafood in the posh neighbourhood of Ginza.

W. Y. : That’s right, in 1953 there were still restaurants that used food stamps.

Y. Y. : Exactly. And I was also mad at Ozu because of that. He represented a world without any financial difficulties, while I, on the contrary, thought that the cinema had a duty to point out those difficulties. There was nothing about the labour unions, or about the security treaty between Japan and the United States. Kurosawa, however, had made a film about the atomic bomb.

W. Y. : Living in fear. During the Shochiku era, there was also Kinoshita Keisuke’s A Japanese Tragedy. And did you actually ever meet Ozu?

Y. Y. :We just crossed paths at the studios.

W. Y. :Me too. He had an imposing presence.

Y. Y. : Exactly.

W. Y. :He was well built.

Y. Y. :That’s what Yamanouchi Hisashi said. One day he was taking a walk along Harumi Street and he saw Ozu and Yamada Tomu walking towards him in the distance. He said he had the impression that a wall was moving towards him! (laughs)He was tall, but it wasn’t just that. He seemed confident, very sure of himself. When you’re young you think, “what has he got to show off about?” (laughs)

W. Y. :He was a good-looking man, and always wore a hat. One day he took it off when he came through the main door at the studio and I could see his thinning hair. I remember that very well.

Y. Y. :He was the age that my children are now, but he already seemed very old at the time.

W. Y. : I still can’t believe that he was only sixty years old when he died.

Y. Y. : But for us, our hopes at that time really lay with Kinoshita Keisuke.

W. Y. : He wasn’t a very tall man, but he had immense powers of observation.

Y. Y. :His style changed all the time, I looked forward to each new film. I always wondered what kind of film he was going to make, while Ozu always did the same thing.

W. Y. :But you wound up making your own version of his film, Tokyo Story, that we didn’t find interesting when we were young! (laughs)

Y. Y. : Yes, I did. The story must have really worked on me in a funny way for me to admire the film so much now.

W. Y. : I enjoyed the story you told me about Oba the last time we saw each other. He told you that we’d been talking about Ozu a lot recently but that he didn’t consider him such an amazing director. “Except for Tokyo Story. God occasionally gives an artist miraculous talent. And that’s Tokyo Story”.

Y. Y. : But I still thought that he must have been a bit jealous. He’s from the same generation as Ozu, he must have heard people talk about him all the time.

W. Y. : It’s an exceptional film. I’m not crazy about Ozu, but out of all of his works, it’s a really good film. Of course there’s the excellence of Atsuta Yuharu’s images, but more than anything Ozu spent a lot of time with his screenwriter, Noda Kogo, in order to create a believable drama.

Y. Y. : Definitely. Ozu’s films are always made up of small stories but this one has a core structure running through it. The parents are lodging with their children in Tokyo but they return to their own home disappointed and sad. It’s universal.

W. Y. : It’s a theme that can be applied to our time as well. The film that you directed, Musuko [My Sons], is similar to Tokyo Story.

Y. Y. : Yes, you’re right.

W. Y. : At the time, I remember you saying that you wanted to do something in the style of Tokyo Story.

Y. Y. : Yes, I was even thinking that it would be better to simply do a re-make of Tokyo Story.

W. Y. : I think it’s a very good film too. The cameraman, Takaha Tetsuo, really committed himself to it. I didn’t think that you would take on another project based on Tokyo Story with Tokyo Kazoku twenty years later.

Y. Y. : I really wanted to imitate Ozu’s film. But how do you go about remaking a major work?

W. Y. : For any artist, that’s the path of humility; following in the footsteps of the great masters.

Y. Y. : It’s said that Leonardo de Vinci imitated famous artists. I’ve never tried to have a critical approach to Tokyo Story. I never thought of adding something of my own at any point. But of course, the eldest son is still alive in my film, which is different from Ozu’s. I eventually became convinced that, no matter what, the film would become my own.

W. Y. : Yes, it is certainly Tokyo Kazoku by Yoji Yamada. That’s exactly what I find so interesting in cinema. Even if you try to imitate something, the result is a completely different work. Ozu depicted a different time period of course, but that’s not all.

Y. Y. : It wasn’t a matter of copying Ozu’s Tokyo Story. I became caught up with the continuity; with the dialogue as well. Like when the grandfather and the grandmother come to Tokyo to stay with their eldest son, they feel that there’s not enough space for them in the house. I thought about this a lot, but before making this film, I was very surprised by the exchanges between the son’s wife and her children in Tokyo Story. The conversation between the mother and her son is so detailed with lots of references to the past. When I write, I do it with a lighter touch. That’s also why I am really inspired by Ozu. Before the camera started to turn, I went out for a meal with Kawamata Takashi.

W. Y. : At that time, he was Atsuta’s assistant.

Y. Y. : First of all, Ozu doesn’t change the angle by zooming in or out. He leaves things the way they are. Apparently he often told Kawamata: “There we are, we’ll leave it like that. Because I’m nice to the customer”. (laughs)

W. Y. : I see! (laughs)

Y. Y. : Changing the angle is dangerous, it can curtail the action. If you leave things the way they are so that there’s no risk of that, you’re better off. Then you add a shot where Hara Setsuko is smiling, or just nodding her head. That’s what Ozu humbly called “being nice” and that really made an impression on me. That’s where we can best get the feel of the special

tempo of Ozu’s films. And he’s so passionate about description. In Norika’s apartment (portrayed by Haro Setsuko), the camera lingers on the surroundings for a very long time. When you watch the film you don’t necessarily realise how long that shot is, but if you time it it’s about thirty seconds. That type of shot usually only lasts twelve or thirteen seconds but Ozu gives it two or three times that.

W. Y. : A true passion. Ozu’s descriptions were never limited to “over there, there’s a mountain”. The descriptions had their own power of expression. The same was true for Kinoshita, but Ozu really brought a special

meaning to it, don’t you think? They say that the close up shot of the swaying corn stalks in Early Summer was filmed by Ozu himself, his own finger was on the camera button.

Y. Y. :At the studios, unit B always took care of the descriptive shots. The director was too busy to do it. But not in Ozu’s films. And when you think about it, he also filmed his actors in that way.

W. Y. :He always filmed with precision.

Y. Y. : Always straight on, just like for the descriptive shots. He managed to capture his actors’ true character. They didn’t need to play their parts.

W. Y. : It’s a bit like he told them: “I’m filming your humanity”.

Y. Y. : Exactly. You feel something like: “Don’t act too much, that’s not what I’m interested in, you’re an amazing woman and that’s what I’m filming”. I completely understand that way of thinking. I also want to direct my actors that way, filming them the way they are. I wonder if it’s because I started my career in the studios where Ozu worked. It’s something that I learned from him and that I made my own.

W. Y. : Right, in Ozu’s films Ryu Chishu simply gives the impression of being there and that’s all.

Y. Y. :When I watch him, I think that he must have played in Ozu’s films and that, in real life, he became the characters that he portrayed. Even after work, when he went back home, he lived like the Ryu Chishu created by Ozu. That’s why he didn’t really need to act at all. He sat in front of the camera, already fulfilling the director’s vision. When you think about it, he’s really an exceptional actor.

Y. Y. :When I’m filming, I get closer to Ozu. (laughs) At the end of the day, the elderly couple leaves the house, but even after they have left, I continue filming the decor of the empty second storey. That’s another moment where you can tell that it’s in the style of Ozu.

W. Y. : A tribute to our big brother. (laughs)

Y. Y. : The most deliberate tribute is in the last scene. I studied the proportions closely, as well as the lighting from Tokyo Story. It’s a very important scene, I was so nervous about it!

W. Y. : Oh, I didn’t know that.

Y. Y. : I even thought about adding a subtitle saying, “This scene is dedicated to Ozu Yasujiro”.

W. Y. : Speaking of this famous scene, there’s one in Tokyo Story where Ryu Chishu tells Hara Setsuko: “It’s going to be hot today, too”. I really liked the scene in your film that echoes this when Hashizume Isao tells Tsumabuki Satoshi on the roof of the hospital that his mother is dead”.

Y. Y. : It’s the father and son. This sentence, “Your mother is dead” contains the words that can reunite these two alienated people.

W. Y. : It was powerful, and it worked well. There are other great moments. And knowing you, you must have thought about this a lot. In the eel restaurant, when the father and mother ask their son : “And so how is work going”, that’s powerful too. You don’t often talk to your father like that. Tsumabuki, who portrays the youngest son Shoji, worked well.

Y. Y. : Yes, he did. He went to great lengths to get it right, he watched a lot of my old films.

W. Y. : After having filmed Tokyo Kazoku and studying Ozu, isn’t Yamada Yoji going to change as well? Well, maybe at his age he won’t change. (laughs)

Y. Y. : Oh, who knows. Studying Ozu and making Tokyo Kazoku resulted in something, I just don’t know quite what.

W. Y. :Because you’re not Ozu. I would love even those people who haven’t seen Tokyo Story to see Tokyo Kazoku.

Interview by Maeno Yuichi

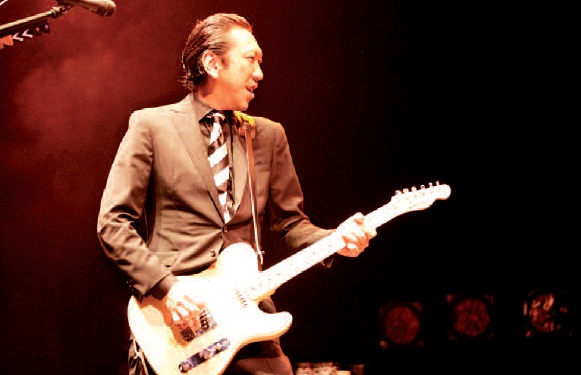

Photo: Private collection