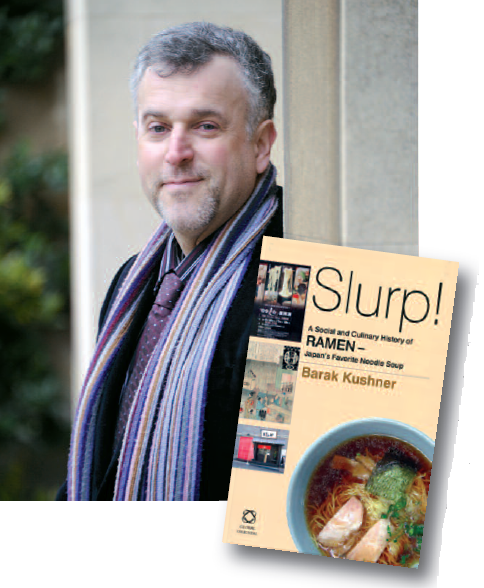

Barak Kushner teaches the history of Japan at the University of Cambridge. He is a specialist in Sino-Japanese relations and his second book, Slurp! A Social and Culinary History of Ramen, was published by Global Oriental (2012).

Barak Kushner teaches the history of Japan at the University of Cambridge. He is a specialist in Sino-Japanese relations and his second book, Slurp! A Social and Culinary History of Ramen, was published by Global Oriental (2012).

What got you interested in ramen?

Barak Kushner: There are two reasons. First, I was interested in the relationship between China and Japan, from the angle of my own individual experience. I wanted to look into the relationship between China and Japan in the long term. There were a few Japanese books about the role of the Chinese in the 1860s. They attracted my attention and made me think of ramen as a symbol of Japanese cuisine, yet it is also so very Chinese. So I decided to study its development. My first contact with ramen was in Yamada, a little fishing town on the northeast coast of Japan. It was badly hit by the tsunami back in March 2011 and partly destroyed by fire, including the place where I discovered ramen. When I lived there, everyday on my way to school where I taught English, I would walk past a grey building that always looked closed. There was never any light on inside and no activity around it. I thought it strange that there was a place like that in a small town but as I was incapable of reading Japanese, I had no idea what the building was. The mystery was solved when a colleague of mine invited me out to eat at 2 in the morning after an evening drinking. The strange building was in fact a ramen restaurant called Rokumon, which means “six pennies”. That’s when I found out that ramen was absolutely delicious. It was my first time and I fell in love with it. I also found out that ramen is the dish that party people eat. And Rokumon’s customers seemed as tipsy as we were. After that, I realised that there were many ramen restaurants in the city and that the Japanese liked to eat the dish at any time of day. And as a historian, I thought to myself that ramen would be a great example to use in order to study the history of Japan and the part that this dish played in its interactions with China, apart from Western influences or other inside forces. Relations with China before and during the reign of the Tokugawa were very important for Japan, but have

been ignored by researchers over the past 50 years.

In the light of the current tensions between Japan and China, might cuisine be able to play a diplomatic role?

B. K.: That’s an interesting question. I don’t think that exchanges of food can calm the tensions between the two countries because people on both sides don’t know much about the subject. But the culinary relationship between Japan and China proves that there have been long periods of peaceful relations between them that shouldn’t be forgotten when immature nationalist behaviour makes an appearance. In fact, exchanges in terms of food have sometimes exacerbated tensions. Nevertheless, the recent passion for ramen in Taïwan and the good image of Japanese food in China over the past thirty years tend to suggest

that things could be improved. Many Japanese ministries use cuisine to promote Japanese culture abroad. It’s an aspect that must not be overlooked. One must remember that only a century ago, Chinese people who came to study in Japan couldn’t stand the local food, whereas now they love it. On one hand, that means that Chinese tastes have evolved. On the other hand, Japanese cuisine has also evolved over a short period of time, by including ingredients they used not to use, such as meat, oil or ramen style noodles. Evidently, cuisine does play an important role, but for a long time the Imperial Palace didn’t serve Japanese food, as French food was preferred. Now, Japanese embassies serve Japanese food. Japanese cuisine is a synonym for sophistication, taste and style. Only 30 or 40 years ago, Westerners didn’t think so.

For several years now, Japanese authorities have wanted their food “labelled”. What do you think of that?

B. K.: All attempts to determine what is authentically Japanese will fail. It is backward looking to consider that the cuisine from Kyôto is the only one worthy of representing Japan. That idea doesn’t take into account the changes in taste over the past few centuries due to outside influences. It becomes complicated to define a cuisine as soon as you try to determine its authentic roots. What is more interesting is to ask ourselves why a country would want to do that. What could it be afraid of? Is cuisine only defined by ethnic criteria? Of course not. It would be wrong to think so. Today, it is all a question of branding. Japan wants to be sole owner of the brand because it is associated with the concept of Cool Japan. But lacking a proper political debate in Japan, soft power has become the answer to everything. Many Japanese believe that popular culture will be their economic salvation. Japan can argue that it has a strong culture, but that is not what will save it. What it really needs is political action and the government’s continued attempt at labelling rests on the erroneous belief that as long as foreigners can take advantage of Japanese culture, they will support Japan.

In many regions of Japan, stories have been written about ramen. Why is that?

B. K.: That trend is related to the one I was talking about previously concerning the government’s branding efforts. I think that several Japanese regions are fighting for survival and that ramen allow them to stand out from the others. Over time, certain dishes have been associated with specific regions although the stories told about them are completely false. Why is Kyûshû broth made with pork when the Japanese didn’t eat pork until the end of the 19th century, while Tôkyô has based its reputation on soya sauce? Isn’t that just a way of categorising one another? How many times have we heard that people from Osaka hate natto [fermented soya] and that people from Tôkyô love it? It’s a way of labelling people to identify them better. And it’s a phenomena that takes place everywhere in the world.

What is the future for ramen?

B. K.: If you rely on certain data, the progressive decrease in the Japanese economy is benefiting ramen because it’s a filling, informal, and cheap dish with a variety of tastes. There are even new tastes developing, such as ramen with tomato and cheese. In addition, ramen is popular in Taïwan and Southeast Asia, without mentioning the instant noodles that have become the most popular fast food in the world. That is why I think the future of ramen is bright.

Interview by O. N.