Since the 1960s, motorcycles have played a considerable role in the world of manga as any manga.

Since the 1960s, motorcycles have played a considerable role in the world of manga as any manga.

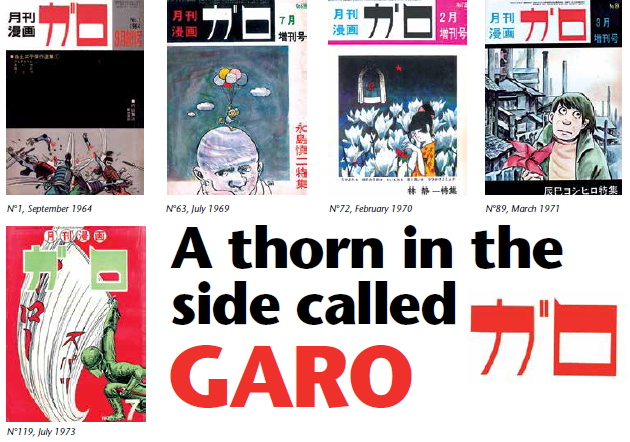

Fan knows, Japanese comics are famous for covering every conceivable subject – often in unexpected ways – and motorcycles are no exception. Manga artists’ love affair with two wheels began in the 1960s and one of the more successful works of that period was Wild 7 (1969-79), an extremely violent story about a secret counter-terrorist motorcycle team whose members are all reformed prisoners. Probably inspired by Robert Aldritch’s film The Dirty Dozen (1967), this manga is also a reflection of that particular time in Japanese history when militant students were regularly clashing with police on the streets and corrupt politicians were making the front pages in the national newspapers. Like other comic stories of the same period (e.g. Golgo 13), it features lots of action, and our heroes often get to ride their missile-launching bikes. Wild 7 ended its run in 1979, but it was the next decade that became the Golden Age of motorcycle manga as several popular titles debuted in the 1980s. Award-winner Futaridaka (Twin Hawks,1981-85), for instance, is the story of the fierce rivalry between two racers. Even artist Hara Tetsuo – of Hokuto no ken (Fist of the North Star) fame – produced a short-lived comic about motocross racing, Tetsu no Don Quijote (Iron Don Quixote), just before embarking on his most famous project. However, although circuit racing stories were popular, young people’s imagination was captured far more strongly by the kind of illegal street racing that was portrayed in titles such as Kaido Racer Go (Street Racer Go). In real life, the so-called hashiriya (street racers) would gather at night for high-speed battles on highways and even Tokyo’s crowded Shuto Expressway, while others still preferred to risk their lives while attacking narrow winding mountain roads. The latter genre was successfully covered by Shigeno Shuichi in Initial D (1995-2013) but while that manga was about cars, Shigeno had previously tackled illegal bike races in Baribari Legend (1983-91).

In fact, this earlier story has many points in common with the more famous car manga of the 1990s. Apparently it was blamed for inciting many young riders to become “rolling-zoku”. i.e. street racers who tried to see how fast they could ride around bends. Criticism aside, the manga became so popular that in 1989 it was even licensed as a video game, produced by Taito for the home console market. While biker culture in Japan was at an all-time high in the 1980s, it usually made the headlines for all the wrong reasons. Illegal street racing was one thing, with gangs like the notorious Mid Night Club speeding up the Bayshore Route between Tokyo and Yokohama at 300 km/h, but even more troubling was the bosozoku phenomenon. These biker gangs were made up of teenaged delinquents and had a nationwide membership of more than 40,000, so it was only natural for comic artists to turn them into anti-heroes of sorts. Two of the most popular bosozoku manga of the time were Shonan Bakusozoku (1982-87) and Hot Road (1986-87). In 2014, the latter was even remade into a live-action film that fared pretty well at the box office. However, the 1980s were not only about violence and illegal activities. Pelican Road (1983-87), for example, tells the story of a high-school student who is crazy about his Honda MBX50 and organizes a motorbike club with his friends. Granted, halfway through the series he finds himself battling biker gangs and other assorted thugs, but this is pricipally a coming-of-age story with the protagonist going through typical teenage experiences like school and romance. In the 1980s, motorcycles and biker culture became so all-pervasive that we even find them in stories that are not bike-centred. Arguably the most famous of all is Akira (1982-90), whose animated version (1988) greatly contributed to anime’s popularity in the West.

Obviously, Akira is anything but a biker story. At the same time though, one of its central themes is youth alienation and rebellion against authority, and the two main characters, Tetsuo and Kaneda, are indeed members of a bosozoku gang. The chain of events that eventually lead to the apocalyptic finale even starts with a battle between rival gangs on the streets of Neo Tokyo. More recently, another biker who has won the hearts of many manga and anime fans is Celty Sturluson, the mysterious leather-clad girl featured in Durarara!! (2009). Based on a ‘light novel’ series, the story takes place in Tokyo’s north-eastern district of Ikebukuro and is a rather complicated mix of gang war, romance and the supernatural, but one thing that stands out among the crowded cast of characters is this so-called “Black Biker,” a headless rider who is really a Dullahan (a supernatural creature from Irish mythology) with superhuman strength who has come to Japan looking for her stolen head, and whose motorbike is in fact her disguised black horse. Celty Sturluson is just one of a new breed of female bikers who has recently popped up in the world of manga. Interestingly, while motorcycle ownership has gradually but steadily decreased in the last 20 years, the increased interest in cutesy “moe” characters and stories has convinced more than one comic artist that cute young girls on bikes would probably sell more copies than macho guys. The cream of the crop in this new version of the biker manga genre seems to be Bakuon!! (lit. explosive loud noise), the story of a group of high-school girls who, tired of riding bicycles up and down the hills on their daily journey to and from school, get interested in bike riding and decide to join the, somewhat far fetched, school motorcycle club. To be sure, manga artists like to mix seemingly incompatible genres and develop strange plots with little regard for traditional storytelling or realism, so they can be forgiven for making their light-weight high-school girls ride powerful bikes. After all, in the late 1970s the protagonist of 750 Rider (1975-85) already used to ride a Honda CB750 Four even though he was only 16, and in real-life Japan Japan one has to be almost 18 to ride such a powerful motorcycle. Speaking of light-weight riders, the essay manga (non-fiction manga) Doko made ikeru kana? (I wonder how far I can go, 2012) features another lady – a 30-something mother of two – who is only 150cm tall and has no body strength whatsoever but still takes up the challenge of getting a licence so she can ride a 200kg 400cc bike. What’s not to love about crazy Japanese comics?

J. D.