Despite the danger they sometimes present, these mountains of fire still have a powerful attraction for the Japanese.

Despite the danger they sometimes present, these mountains of fire still have a powerful attraction for the Japanese.

On the 27th of September, a few hundred people who were looking forward to enjoying the first colours of autumn set out to climb to the summit of Ontake-San. The weather was perfect and the day looked promising, but at around midday a column of smoke veiled the area, announcing one of the most lethal eruptions in decades. As many as fifty people had lost their lives by the end of the rescue effort, which was interrupted several times due to typhoons. This incident came as a reminder that active volcanoes pose a high risk to the country and that they are unpredictable, despite the continual monitoring of the most active sites by the Japan Meteorological Agency. The agency did note a few unusual signs of activity, but did not change the alert level at the time from level 1, or normal. The alert level has risen to 3 since the deadly eruption, which means it is now forbidden to approach the volcano. As Japan is a country dotted with many active volcanoes, the government uses a system of 5 different levels to warn the public of the dangers. Just as they have to live with the threat of earthquakes, the people also need to come to terms with these mountains, which could become dangerous at any moment.

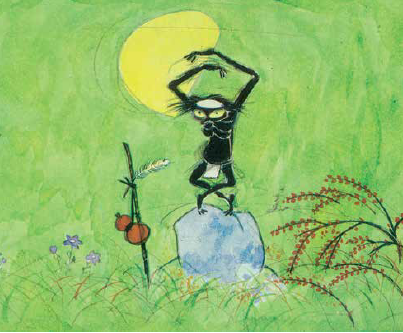

Japanese volcanologists estimate that major eruptions happen once every 10,000 years, although it is difficult to predict the moment when they might occur. This doesn’t mean that the Japanese live in constant terror of erupting volcanoes. For centuries they have learnt to live with violent forces of nature in whatever form they take. Volcanoes are part of the country’s identity. They are part of the landscape, and for some they are highly symbolic. Fuji- San, or Mount Fuji, has even become a globally familiar icon since it was registered as a World Heritage site. Without this volcano, Japan would not quite be Japan. When you’re in Tokyo, and at a great enough height, you can unconsciously find yourself looking around to find Mount Fuji, as if to take comfort in its presence. This is quite a paradox, especially for a mountain that can cause such damage, and maybe it truly is home to a mighty kami, a shinto deity to whom one needs to pay tribute to in order to ensure continuing benevolence and assuage its anger. This majestic volcano is incredibly beautiful, inspiring Japanese artists like the famed Katsushika Hokusai, whose images of it continue to be the highlight of many exhibitions around the world. The Italian writer Fosco Maraini, who was deeply familiar with Mount Etna in his home country, wrote that “Mount Fuji is flexible, upright and proud as a sword, encouraging boldness. Mount Fuji makes one think of a young virgin – it’s no coincidence that it might be the home of ‘the princess who makes trees blossom. – or of a young warrior fighting for his beliefs. That’s why Mount Fuji embodies love, death and all other kinds of great turmoil”.

Fuji-San is not the only volcano in Japan that has such power to fascinate people, many who don’t think twice about settling down in the vicinity despite the potential danger. Sakurajima, at the tip of Kuushu Island, is another excellent example. In contrast to Mount Fuji, which is considered dormant and last erupted in 1707, the “cherry tree island” volcano continues to emit smoke that residents have to endure on a regular basis. Aso-San can also be found on the same island, and is a group of around fifteen volcanic cones inside a 24 by 18km caldera with a 128km circumference – one of the largest in the world. It is a beautiful place that never fails to amaze all those who visit it, and is the only place in Japan where tourists are able to watch the black plumes of smoke rising from a volcano while they stand on the edge of the crater. Bunkers have been built on the mountain slope to protect visitors in case of a small eruption, but sometimes access is forbidden in the event of strong gas emissions. Further up north, in the beautiful region of Tohoku on the northeastern side of the largest island of Honshu, stands Zao-Zan, or Mount Zao. This whole area is a real gem of nature and many people come to take advantage of the thermal waters (onsen) in the region. The presence of all these volcanoes explains the abundance of the warm springs, which the Japanese absolutely adore, the opposing elements of fire and water coming together to provide the greatest of pleasure for the whole country. Some people are ready to travel hundreds of kilometres to enjoy these places where, in the space of a few hours or days, they shed their worries in the depths of water that springs from the bowels of the earth. Despite the risks they present, volcanoes have always had, and will continue to have, the greatest of attraction for the Japanese, who cannot live without them. They are part of their daily lives, they respect them and even worship them, as proven by the Shinto shrines erected close to or at the summits of these fiery mountains. Even though it may prove a risky endeavour, and doubly so in the light of the recent eruption at Ontake-San, there will always be those who set out to climb Japan’s volcanoes and admire their beauty.

“A sky without colour

Meets The sea

the colour of ashes”

Haiku by Ogiwara Seisensui.

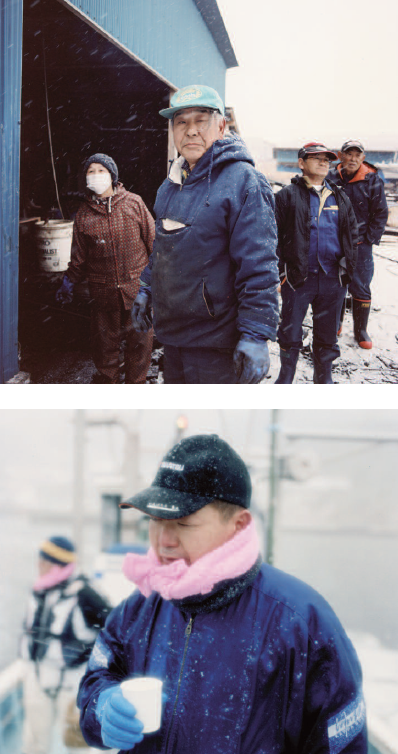

Odaira Namihei

Artist of the painting: Katsushika Hokusai

Photo: DR