In the space of five decades, this ancient and once tranquil district has become one of the foremost centres for international fashion.

In the space of five decades, this ancient and once tranquil district has become one of the foremost centres for international fashion.

It can’t be repeated too often that Tokyo’s 1964 Olympic Games had an incredible impact on the appearance of the Japanese capital. For a long time, Harajuku was famous for its tranquillity and its rice fields. It was transformed in just a few years after Tokyo was chosen to host the 18th Olympiad of the modern era and became a prominent location for culture and fashion in Japan. Harajuku has become a trendsetting hotspot. It all began in 1958 when the Harajuku Central Apartments were built. Tokyo Plaza Omotesando has now replaced the original building but it is still here that many artists and intellectuals choose to live. Café Léon opened on the ground floor and became the meeting place for all kinds of creative people. Unlike Shinjuku, its famous neighbour with cinemas showing French Nouvelle Vague films, and where the foundations for a cultural revolution were laid at the end of the 60s, Harajuku is rather more dedicated to art and design. Artists such as Sakamoto Ryuichi liked to spend time at the Café Léon. Little by little, fashion took over, and in December 1973, An An magazine, the Japanese equivalent of Elle, published a long article about Harajuku and the fact that many young “AnNon tribe” women (AnNon zoku, a reference to the magazines An An and Non No that were very fashionable at the time) would hang out there.

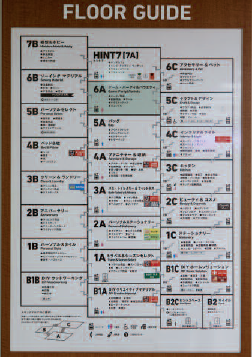

The shops run by these young creative people attracted street artists and Tokyo’s youth, especially middle- and high-school pupils, who took advantage of the car ban in Omotesando to meet and dance from morning till night. They were nicknamed the “Bamboo Shoot Tribe” (takenoko zoku, in reference to the Takenoko shop owned by Otake Takenori, where they bought their clothes). The action spilled out into the streets and, bit by bit, the appearance of the streets changed. Takeshita Street, right by the station, underwent the most radical change. In 1987, this long street, which for many years had been home to many hostess bars, saw the arrival of the first shop to be connected to a television broadcast. It was called Genki ga deru hausu [A home in which you feel happy] and was developed by the Nippon TV channel. It became a hit and shops like it multiplied, spurring on a a period of talent hunting. Since the Sunday car ban was introduced in the late 70’s, Harajuku had space for people to meet and the area around Omotesando developed into a vast open-air concert hall where dozens of bands could perform. It attracted hordes of people and maintained the myth of a district dedicated to creativity. Fashion shops prospered along the main arterial roads but Harajuku’s centre of gravity progressively moved towards Ura Harajuku, a district full of small streets where young designers were able to rent places at affordable prices. Young people in search of their own style found everything they were looking for in these shops. Without being too sophisticated, street fashion progressively took over, spearheaded in 1997 by A Bathing Ape, which was set up in Ura Harajuku and attracted thousands of young people on the lookout for novelty. It didn’t take long for Propeller Street and Cat Street to see shops sprouting up like mushrooms. The success of Japanese pop culture across the world at the start of 21st century has contributed to Harajuku’s increasing popularity.

In the past, when foreigners came, it was mainly to visit the Oriental Bazaar, a shop specializing in Japanese souvenirs, from replica swords to tea bowls, or Kiddy Land, a toy shop full of gadgets that were popular at the time. These two historical shops still exist but a visit to them is no longer a priority. Nowadays, what everybody in Harajuku wants to be is kawaii (cute). Kept in the public eye by the media, this fashion style is eagerly sought out by many young Japanese and thousands of foreigners who walk up and down Ura Harajuku’s streets every weekend. It is the vibrant mix of different styles that makes the area so pleasing. In 2004, American singer Gwen Stefani celebrated the district in her song, Harajuku Girls. “I’m fascinated by the Japanese fashion scene, just an American girl in the Tokyo streets,” she sings in her song that became an international hit, definitively recognizing Harajuku as being one of the world’s foremost fashion centres. Furthermore, just as it has done over the past five decades, the neighbourhood has continued to change and develop. In 1964, Harajuku completely altered its previous existence in the space-time continuum and it hasn’t stopped since then. It’s a place where you might have unlikely encounters. “One beautiful morning in April, on a narrow side-street in Tokyo’s fashionable Harajuku neighbourhood, I walked past the 100% perfect girl,” wrote Murakami Haruki in one of his essays. Everything is possible in Harajuku, and that is why Zoom Japan decided to ask three of the neighbourhood’s inhabitants to be our guides. Three original and complimentary perspectives on entering the heart of Tokyo.

Odaira Namihei

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat