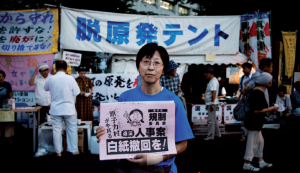

Even though she doesn’t have any children, Kusano Mie has understood that a healthy future needs to be ensured for birth rates to rise.

Even though she doesn’t have any children, Kusano Mie has understood that a healthy future needs to be ensured for birth rates to rise.

At 52, Kusano Mie has never had any children, but we wanted to give her a platform after all she has done as the “maternal heart” of the action to help children of the Fukushima prefecture where she herself grew up. This native of Shirakawa saw “the land of her childhood collapse in March 2011”. She now believes that “fear of contamination will be an obstacle to the creation of new families in Japan. In the Tohoku region, as well as in other areas of Japan”. She had been living in Main for seven years, with her husband, Steve Athearn, and was devastated by March 2011’s tragedy. “My mother, my brothers and sisters as well as all their families live in Fukushima,” she explains. “My young nieces and nephews live in Fukushima, Koriyama and Shirakawa, the city where I was born. Now, that zone is badly contaminated because the Abukuma River flows across it”. Mie tenderly remembers all the happy hours she spent in this Japanese province. “When I think of my childhood, I see lilacs planted in the middle of a dark forest: it’s like a never-ending spring day”. Since March 2011 she says that “everything has changed. The farmer throws his produce away. The surface of the ground needs to be removed and is deprived of its essential micro-organisms. The children can’t touch the grass in the garden, and most of them will never be able to go home because everything is contaminated”. A feeling of guilt overwhelmed Mie. “I regret, and I am ashamed that when the Fukushima power plant was built, I said nothing. That is why I wish to contribute to repairing our soil”. Mie’s father died in November 2011 and her mother needed treatment for breast cancer. “I went to live with her. My family needed me,” she says. But when she got there, Mie became involved in another form of action. “I also wanted to help my family leave Fukushima. The Japanese government ordered the evacuation of people living in areas with a radiation level over 20 millisieverts per year. But that also means that many residents are still living just under that limit daily. It might be lower than the level specified but it still exists. Most people are aware of the risk they take, but often they don’t have the means to leave the area where they live. And it’s also reassuring to stay in familiar surroundings, even if it isn’t safe anymore,” she confides. Mie decided to take action locally and joined Honda Takafumi, who founded the World Network for Saving Children from Radiation in June 2012. This international organisation aims to protect children from nuclear and radioactive danger. “We share news and information on the effects of radioactivity on children. We also participated in creating a citizens’ clinic in Fukushima. We hope that this place can give answers to worried mothers’ questions and find solutions to the illnesses that might develop in the future. The children who were subject to the strongest radiation will follow a 24 day treatment, three times a year for 10 years”. According to Mie, “fear of contamination will add to the financial problems that young people are encountering. Having a child is a heavy financial responsibility in Japan. This country needs to change the way it thinks about life, the economy, culture and industry”. In March last year her sister-in-law, Nozomi, gave birth to a little girl. “They both live with my sister- in-law’s husband, Yoshitaka, in Shirakawa. It was quite a challenge; throughout her pregnancy she was afraid of contamination,” she says. They probably called their daughter Nozomi to ward off bad luck. It means “Hope” in Japanese.

J. F.

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat