First it was sushi, now French consumers have discovered the pleasure of noodle soup. Zoom Japan investigated.

First it was sushi, now French consumers have discovered the pleasure of noodle soup. Zoom Japan investigated.

Aware of the large part that popular culture plays in both the commercial interests and image of the country, the Japanese government is now redoubling its efforts to promote manga, literature and cartoons, as well as cuisine. The growing trend in sushi and yakitori (chicken kebab) restaurants has led to the creation of many so-called Japanese restaurants in Paris, where quality is of little importance.

In response, the Japanese authorities have put together a Japanese food evaluation committee in charge of making a list of establishments serving authentic Japanese cuisine since 2007. They have launched a new initiative under the name Mog Mog Japan, whose ambition is to present “real Japanese restaurants in Paris” (as stated on their Facebook page) and publish an annual guide with a target circulation of 30,000 issues in the first half of 2013. Six years ago, the booklet did not include a single ramen restaurant. Was this a deliberate oversight or was ramen not yet considered “authentically” Japanese? At the time, no explanation was forthcoming. The French had already begun to discover sushi and sashimi, which were considered to be delicacies, but were still not greatly attracted to noodle dishes. Nowadays, sushi is sold in supermarkets and has developed a French clientele. You also need only walk down rue Sainte-Anne in Paris at lunchtime to see never-ending queues outside the principal ramen and udon restaurants. In London, the continuing increase in the number of restaurants specialising in ramen, such as the excellent Bone Daddies in Peter Street or Shoryu Ramen in Regent Street, is proof of this growing enthusiasm. Just as in Japan, the British choose to eat ramen as an informal meal at an affordable price (even though prices tend to be on a level with other meals in London), but unlike Japanese consumers, the British know little about the origins of ramen. However, knowing a bit more about the dish can lead to a better understanding of the development of Japanese thinking over the past 150 years. Opening up to the rest of the world, including China, was essential in promoting the distribution of noodles throughout the archipelago. “It was at the beginning of the Meiji era, when Japan was starting to open up to the world, that noodle cuisine, originating from China, appeared in the Chinese quarter of Yokohama. At the time it was mainly shio ramen, meaning salt-based ramen. The Japanese added their soya sauce to the broth, creating shoyu ramen that progressively spread across Japan. During this process many local versions appeared. That is why there are approximately forty different kinds of ramen nowadays. In a country where local products, especially food, are quite distinct from region to region, only noodles have managed to conquer the whole country,” says food historian Hantsu Enda. It was only in the twenties that ramen shops started opening up in every city. The low prices especially pleased the working classes as they were able to afford a good meal. Most restaurants open up near to railway stations or in shopping arcades (shotengai) in the city centres.

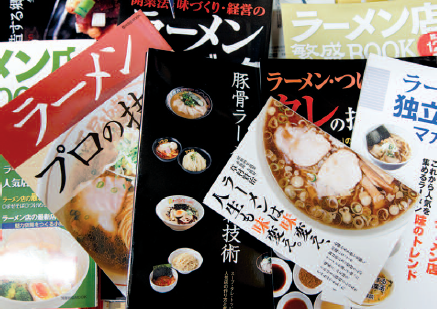

“In Western countries the ramen dishes you get in restaurants are rather more expensive than ordinary food, but in Japan the opposite is true. In our country, taking a bill for 1,000 yen [£7] as the standard, every dish that is cheaper is placed in category B (Bîkyu gurume), meaning that it is a simple, easily consumed dish. A bowl of ramen usually costs between 600 and 900 yen. That contributed towards its great popularity. The second reason for it’s popularity is related to the fact that ramen fit in perfectly with Japanese eating habits. For a long time the vast majority of Japanese meals could be summed up by ‘rice, a side dish, and a bowl of miso’. And there is an expression in Japanese that perfectly describes Japanese eating habits: shushoku purasu ichiju issai (a staple food, a soup and a side dish). Uniquely, a dish of ramen combines all of these elements on one plate,” adds Enda. Ramen conquered the whole population after the Second World War. In Ozu Yasujiro’s film, The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice (Ochazuke no aji), released in 1952, one scene demonstrates perfectly how a whole part of the population, until then only used to other dishes, discovers ramen. A young woman walks into a ramen restaurant for the first time and is initiated by one of her friends. “It’s hot,” she says, as she brings the bowl full of broth to her mouth. “That’s why it’s so good,” is what she is told. The young woman is rather clumsy while eating the ramen, in contrast to the boy who is completely at ease in this “good and cheap” place. Over the following years, enthusiasm for ramen continued to grow, resulting in the creation in 1958 of the first instant ramen (sokuseki ramen) by the Nisshin company, gaining immediate success. When the same company launched its cup noodles in 1971, ramen became the Japanese answer to MacDonalds, which opened up throughout the Archipelago in the same year. Itami Juzo’s film Tampopo (1985) honoured this dish, which has become an inseparable part of Japanese popular culinary culture. “The idea of making ramen the main theme in the movie has not only contributed to reinforcing its popularity but it has also given it a better image. Ramen restaurants have seen their status grow. Until the movie was released, most Japanese didn’t have a very good opinion of ramen restaurants but Tampopo changed that. Now, the restaurant owners have become famous and the profession is one of the most respected,” confirms Enda. All you need to be convinced is to go and visit one of the bookshops whose shelves are piled high with books dedicated to ramen.

Odaira Namihei

Photo: Jérémie Souteyrat