The second-largest foreign community in the archipelago after the Chinese, their presence can be explained by many factors.

Japan’s ties with Vietnam are quite old, but their love affair has grown significantly in the last 30 years – though at times it looks more like a money-driven marriage of convenience. In the mid-1990s, for instance, Japan resumed its Official Development Assistance (ODA) to Vietnam, providing support in such areas as infrastructure development, healthcare, education, and rural development. Foreign-minded Vietnamese, on their part, have chosen Japan as one of their favorite destinations, and their community in Japan has grown significantly over the years. As of June 2024, there are over 600,000 Vietnamese residents in Japan. This makes them the second-largest foreign community in Japan, just behind the Chinese (844,000).

However, when it comes to foreign workers, the Vietnamese are by far the largest community. According to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, as of October 2023, 2,048,675 foreigners were working in Japan, including 518,364 Vietnamese or around 25% of the foreign workforce (the Chinese were second with 19.4%). Vietnam overtook China in 2020, and the gap in numbers has continued to increase since then.

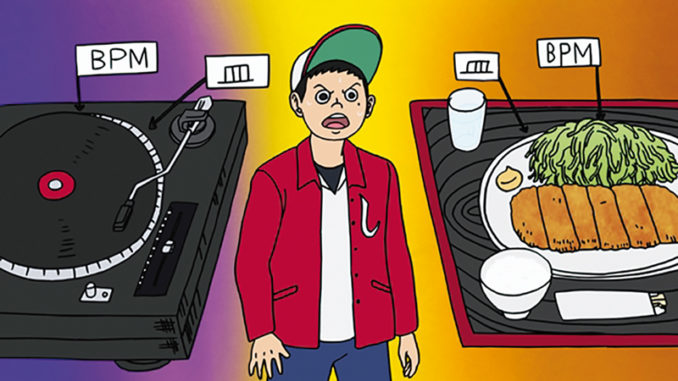

Of the approximately 520,000 Vietnamese working in Japan, the largest group belongs to the Technical Intern Training program (209,300 people). The second largest is Technical / Specialist in Humanities / International Services. It includes engineers and overseas business managers (84,700) and increased more than 20-fold in 10 years.

Many Japanese prefectures are trying to secure talented human resources from Vietnam and other countries to address the labor shortage caused by population decline and aging. There is a high demand for workers in a wide range of industrial fields, including agriculture, nursing care, tourism, IT, manufacturing, and construction. In February 2023, for instance, 12 companies from Shizuoka and Yamanashi prefectures held a joint recruitment interview session for highly skilled personnel at a hotel in Hanoi (the previous two times, in 2021 and 2022, they were held online due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

Prefectures are paying attention to Vietnam not only to secure workers for the local economy but also to support their companies’ overseas expansion. In the 2023 Survey on Overseas Business Expansion of Japanese Companies conducted by JETRO, Vietnam ranked second for the seventh consecutive year as a future business expansion destination. The top reasons why companies like Vietnam include “market size and growth potential” and “low labor costs and abundant labor force.”

While workers comprise the largest segment of the Vietnamese community in Japan, they are not the only group. The oldest colony is made up of war and political refugees. The Vietnam War, which ended in 1975, was not only a conflict against the United States but also a civil war between the North and the South. When the North won, many of those who fought on the side of the South Vietnamese government (and the United States) were politically persecuted and began to leave the country, particularly in the late 1970s. Most refugees went to the United States, but many also emigrated to France, Australia, Canada, and Japan.

Vietnam and Japan have a deep historical connection and generally speaking, many Vietnamese people are pro-Japanese. They also admire Japan as the first Asian country to achieve modernization. These are among the reasons that encouraged some refugees to emigrate to Japan. According to statistics by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan welcomed more than 11,000 Vietnamese refugees.

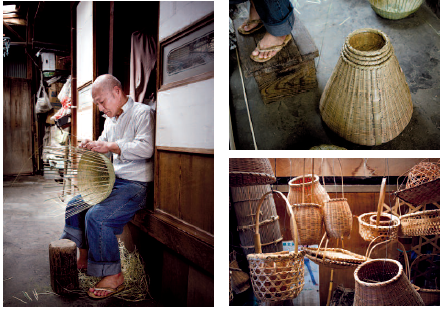

However, the postwar chaos and political persecution were not the only reasons for the exodus of refugees from Vietnam. Indeed, many people left their country as so-called boat people, especially in the latter half of the 1980s. They were often economic refugees, unlike the political dissidents of the immediate postwar years. After the war, the winning North imposed a socialist regime but the economy suffered from stagnation, and people fled the country due to economic hardship. Many of the refugees came from fishing villages, which were particularly poor.

Vietnamese refugees and their families are said to be living “at the bottom of the barrel” in Japan. Although first-generation refugees have lived in Japan for a long time, they have difficulty assimilating into Japanese society due to language barriers, culture, and differences in values. Some second-generation refugees go on to university and find employment but many are unable to keep up with their studies, drop out of high school, and fall through the cracks. Even the family members who are brought from Vietnam face similar problems.

People engaged in the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) are by far the biggest group in Japan. As stated on the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare website, “The purpose of the TITP is to transfer skills, technology, and knowledge to developing countries and to cooperate in the development of human resources that will lead to their economic development.” This system was established in 1993 based on an older training system from the 1960s.

The industries which accept technical intern trainees are diverse, including agriculture, fishing, construction, food manufacturing, textile and clothing manufacturing, machinery and metal manufacturing, caregiving, etc. In terms of country of origin, the Chinese used to be the most common, but now the Vietnamese make up the biggest number.

The TITP has faced several criticisms over the years. To begin with, while the Technical Intern Training Act states that, as a basic principle, “technical intern training must not be conducted as a means of adjusting labor supply and demand,” in reality, technical intern trainees are often used to address the labor shortage, which has been rapidly increasing in recent years.

There have also been many cases of exploitation and abuse as trainees have reported experiencing long working hours, unpaid wages, and even physical abuse. Some reports have gone so far to label TITP as a form of forced or compulsory labor.

The program also restricts trainees from changing workplaces, which can lead to situations where they are stuck in abusive or exploitative environments.

In Vietnam, the TITP is a big business involving corrupted politicians, the sending agencies, and the police. It costs about one million yen to go to Japan for work training. This causes many young people living in rural areas who want to go to Japan to go into debt. It is said that coming to Japan with such a large debt is one of the reasons why some trainees turn to crime.

Nguyễn Thị Thanh Nhàn, the Chairman of AIC Group, has been involved in several high-profile cases related to procurement violations and has faced legal actions. Despite these controversies, the Japanese government awarded her the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette in 2018 for her contributions to strengthening Japan-Vietnam relations. In 2022, she was found guilty and sentenced to 30 years for violating procurement regulations and bribery. She has been on the run since and is currently wanted by authorities.

In recent years, the number of Vietnamese coming to Japan as international students has increased rapidly. According to a survey by the Japan Student Services Organization, in 2018 there were 72,000 Vietnamese students, accounting for 24% of all international students. However, their number has decreased after the pandemic, and in May 2023 they were down to 36,339. This, however, still makes Vietnam the third-largest source of international students in Japan, following China and Nepal.

Some Vietnamese students come to Japan after graduating from high school; others transfer to a Japanese university while enrolled in a university in Vietnam, or enter a graduate school in Japan after finishing university in Vietnam. Many Vietnamese come to study the Japanese language before enrolling in college.

There is no accurate data on the career paths that Vietnamese international students choose after graduating from Japanese universities, but many of them are thought to find employment in Japanese companies in Japan. Some return to Vietnam and work for Japanese companies with offices there, and some become Japanese language teachers in Vietnam. Apparently, if you have studied in Japan and can speak Japanese, it will not be hard to find a job when you return to Vietnam.

Gianni Simone

To learn more about this topic check out our other articles :

N°149 [FOCUS] Tokyo : Working to Support Their Loved Ones

N°149 [Encounter] Ties That Are Growing Weaker

Follow us !