It’s the same old story: everybody knows such iconic pop culture characters as Superman, Batman, Hello Kitty and James Bond, but few people can name their creators – same thing for Godzilla. So far, the Big G has appeared in 33 Japanese and five American feature films. Still, only hardcore fans of the King of the Monsters know Honda Ishiro, the man who directed eight of those films, including the original 1954 Gojira, and can be considered the most internationally successful Japanese filmmaker before Miyazaki Hayao.

To be sure, Honda’s 50-year film work goes well beyond Godzilla. He made 46 films, ranging from drama and comedy to war and science fiction, but it is undeniable that he has earned a special place in the history of cinema for the influence he has had on disaster and monster fantasy movies.

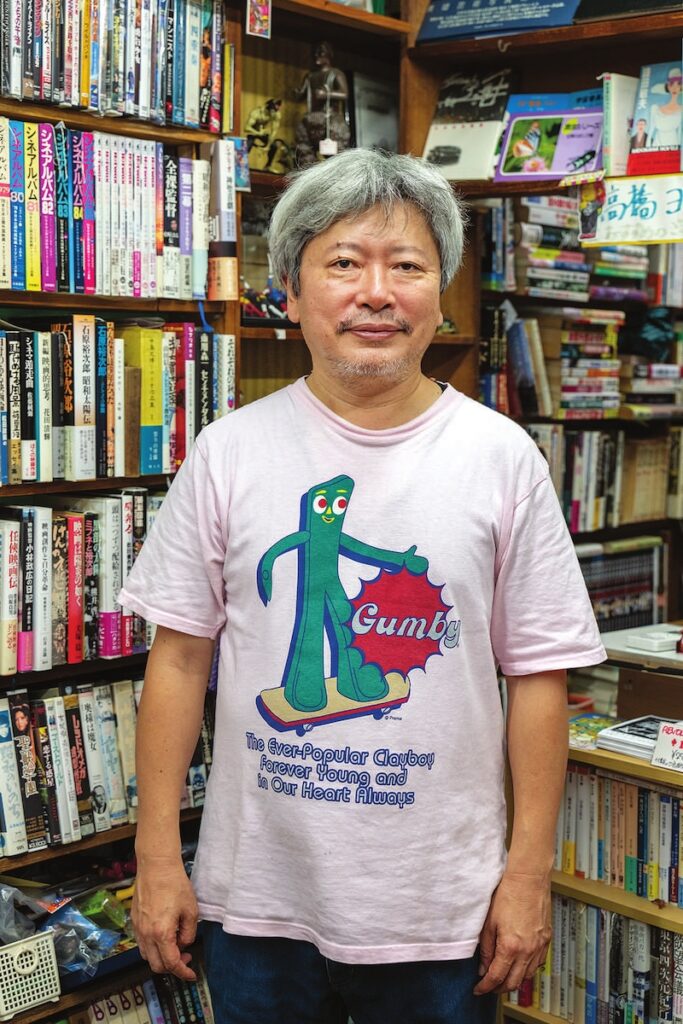

Zoom Japan talked about Honda’s work with Kiridoshi Risaku, a literary critic, screenwriter and film director who specializes in cultural criticism and is the author of Honda Ishirō, mukan no kyoshō (Honda Ishiro: The Uncrowned Master) (2014).

In his book, Kiridoshi looked at the scripts that Honda himself owned in which he added copious notes and specific directions and compared them with each of his film works. This was the first time someone examined and analyzed in such detail what Honda actually did on the set.

Kiridoshi’s book was born from a series of articles and essays he wrote about Honda. “Originally, ‘uncrowned master’ was the title of a two-part article I wrote 20 years ago for a magazine,” Kiridoshi says. “The title was chosen by the editor, but I found it fitting for the subject and used it for my book too. When you think about it, Honda’s work has been barely recognized, particularly in Japan. Overseas, he is highly regarded by such directors as Quentin Tarantino and Guillermo del Toro, yet he never won any major awards and has been constantly overshadowed by Toho’s special effects director Tsuburaya Eiji or music composer Ifukube Akira. Honda is rarely in the spotlight. He never stood out, even as a person. He preferred to stay in the background, quietly working on his movies without much fanfare.”

Both Kiridoshi and other critics find that Honda’s work is fundamentally different from other directors because he managed to create his own cinematic world. “First of all,” Kiridoshi says, “what sets him apart from other directors is that he realistically captured and interpreted how humans react when they encounter something as incredible as a giant monster. He was the first person to achieve such an effect. Of course, everybody knew that those monsters didn’t exist in reality, but he worked really hard to make it look as if they were real, and did it with style.

“In later years, Toho decided to explore different paths, for example by adding a little more comedy, a few playful elements, or incorporating some Hong Kong karate-like action, but Honda always tried as much as possible to stay true to the original story, the fear and terror and tragedy of a monster wreaking havoc in people’s lives.”

It is often said that Honda shot his films like documentaries, and Kiridoshi says that his films are full of examples corroborating this opinion. “Honda was originally interested in people facing natural phenomena,” he says, “and his early directorial works, even before he made Godzilla, have such a theme. When he was young, he was an avid moviegoer and was particularly awed by Robert J. Flaherty’s Man of Aran (1934) even because he had a profound love for the ocean. The movie depicts man’s severe battle against nature on a small rocky Irish island surrounded by the rough sea. As there is very little soil on Aran, they make vegetables by covering the rocks with seaweed.”

Man of Aran is a docufiction, i.e. a narrative film with a documentary touch. Even Honda’s early works, like The Blue Pearl (1951, on the everyday life of women pearl divers) and The Man Who Came to Port (1952, about gunners on a whale hunter boat) are documentary-style feature films. “When Honda made Godzilla, I think he looked at it from that perspective,” Kiridoshi says, “i.e. he wanted to make it look like it was happening for real. For example, when the ships are destroyed at the beginning, we still don’t know it was Godzilla’s doing, and both those scenes and the reactions of the families of the people who were lost at sea are very realistic.

“Honda was good at moving big groups of people, like when they flee the monster. He also used real members of the Self-Defense Forces and the Japan Coast Guard instead of actors, and skillfully moved them like they had been really deployed at the scene of the attacks.”

Another thing that has been pointed out about Honda’s work is that, unlike other film directors, he wanted to control even the smallest details in his films, from the initial design stage and planning to the script and dialogues. For instance, Honda utilized nine different film editors over the course of his 25 fantasy films, and it is generally assumed that he did his own editing by simply telling the editor when and where to make the cuts. Also, there are a few candid photos of Honda on a set showing him closely coaching his actors while holding onto a rolled copy of the script which he carried around with him religiously during filming. The director was particularly keen on dictating the physicality of his actor’s movements and gestures to a precise degree, walking them through their scenes, showing them how he wanted them to move, how to react, and even which buttons to push on a console. This hands-on approach is said to have put the director’s stamp on his films.

“Film making is a team effort,” Kiridoshi says, “and I don’t think that Honda was closely involved in all aspects of his work. The parts where monsters and super weapons appear were obviously left to the special-effects director, while the producer was in charge of planning and the scriptwriter was responsible for the story, so some people may have a limited image of the director of a fantasy special effects film, thinking that all he does is coordinate the actors’ acting, or a “craftsman” who skillfully manages each scene. However, when I wrote my book, I read the scripts used during the shoots and noticed that many parts differed from the actual film. This makes me think that Honda must have made some changes to improve the film and make it look more realistic. Even after the script was written, he had no qualms about tweaking it here and there.”

When directing a scene, Honda was always thinking of how the live action would later be integrated with the effects footage to follow. He almost precut the movie in his head. A single take in a Honda film typically lasts just a few seconds, and 30 seconds was about the maximum.

“Indeed, he was very good at matching the special effects with the story,” Kiridoshi says, “making sure that the special effects reach a proper climax, such as intentionally inserting quiet scenes before the monster attacks. Other directors treated such stories just like action movies or entertainment. However, for Honda, the battles and special-effect scenes were only a part of the story. He wanted to go deeper and make the audience think about why those things were happening on the screen.

“Let’s not forget that the original Godzilla story was written by novelist Kayama Shigeru. Honda was only the director and joined the project midway through. But then he went on and changed the story to better express his message that nuclear testing had given birth to Godzilla. For example, Kayama’s original story has a hopeful ending, in which nuclear testing around the world is voluntarily suspended. But Honda changed that. He said, “Is it possible for humanity to turn back now that we have entered the nuclear age?” He felt that with America and the Soviet Union constantly threatening a nuclear war, there could not be such a sweet ending. He wanted people to reflect that the future would be far from rosy.”

Regarding Honda’s relationship with Toho, one of Japan’s major film companies, Kiridoshi points out that the director worked for the same company throughout his career, even when he became a freelancer. “The original Godzilla came out in 1954,” he says, “while his last two Godzilla movies came out respectively in 1969 (All Monsters Attack) and 1975 (Terrorr of MechaGodzilla). As you can see, there was a gap of a few years between the last two films, but during those 20 years or so, when it comes to special effects films, Honda is the first director who comes to mind. The Toho management was constantly putting pressure on him to make things more extreme, more violent, or add more comedy-like scenes, but he tried as much as possible not to betray his original vision.

“But that’s not all, of course. He was very eclectic. Being a Godzilla fan, when I researched my book I found out that at Toho they thought he wasn’t really suited to special effects films and would be better suited to home dramas.”

Many of Honda’s former colleagues felt that the vast majority of the films he directed were done not by choice but by assignment. Also, in the second half of the 1960s, he did not like producer Tanaka Tomoyuki’s decision to infuse the monster films with humor to make them more attractive to a younger audience but admitted in later years that he could never really oppose Toho’s changes.

“It’s true that he wasn’t thought of as a director with much individuality,” Kiridoshi says. “Some called him a loyal company man, or a clock-puncher, especially when compared to directors with strong auteur qualities like Kurosawa Akira and Ozu Yasujiro who had established their own distinct style. Even so, I think the reason he was able to work for Toho for so long was because he was quick and reliable, and usually made good movies and earned good money for the company. In a sense, his misfortune was that Godzilla became so big that in the end, it totally overshadowed him and the other directors who made those films. It’s a little bit like Sherlock Holmes: everybody knows the famous amateur detective but few people can remember the name of its author. In Honda’s case, his monster films were the product of the studio system of the time. Honda loyally followed Toho’s wishes to ride the special-effects boom, and when the boom ended, so did Honda’s career as a director.”

Gianni Simone

N°145 [TRAVEL] A Quick Trip to Tokyo with Godzilla

N°145 [FOCUS] Godzilla and 1954’s Japan

N°145 [FOCUS] A phenomenon : Forever in our memories

Follow us !