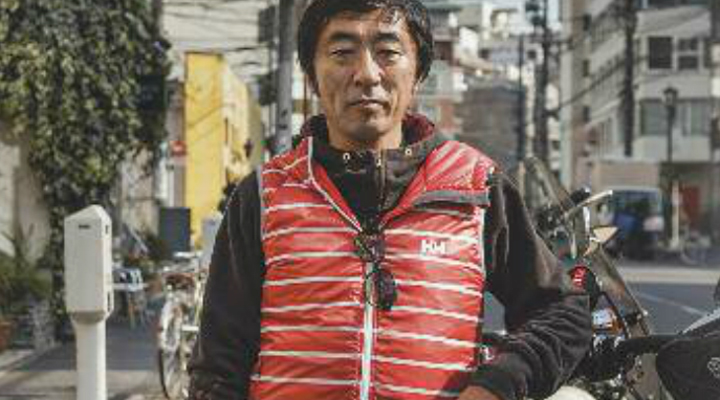

A leading figure in the debate about ideas, the intellectual agreed to paint an uncompromising portrait of Japan.

Few people have shaped the social, political and cultural debate in Japan like Uchida Tatsuru. Born in Tokyo in 1950, since 2001, the 73-year-old thinker and martial artist first made his voice heard through his popular blog before getting noticed by the publishing world and unleashing a seemingly endless stream of books through which his sharp and curious mind has explained modern French thought and tackled Japan’s troubled history, uncertain future and the country’s problematic relationship with America and China. In 2012, he even contributed the essay “About the Pathology of Japanese Media” for our special edition about the aftermath of the triple disaster in Tohoku.

A long-time resident of Kobe, Uchida is professor emeritus at Kobe Jogakuin University and director of Gaifukan, a cultural and community centre he opened in 2011. He won the Kobayashi Hideo Award for Private Version of Jewish Culture and the Shinsho Award for Japanese Frontier Theory. Other books include Ethics of Hesitation, Levinas and the Phenomenology of Love, The World Turns into Monkeys and Futurology of a Declining Society.

Unfortunately, none of his books have been translated into Western languages. So, we decided to introduce his thought to our readers. The following conversation took place at his Tokyo apartment.

According to your profile, you are many things, among them a French literary scholar with a particular interest in modern French thought. Why are you so interested in French culture?

When I was a high school student in the 1960s, the humanities and social sciences were dominated by French authors from Sartre and Camus to Levy-Strauss, Merleau-Ponty, Lacan, Foucault, Derrida and Levinas. All of them were French. No British, German or American thinkers were so popular in Japan at that time. The problem was that I couldn’t speak any French. I heard their books were amazing, but there were no translations available. So I had no choice but to learn to read French. Everyone studied French around the end of the 1960s. All the would-be Japanese intelligentsia could at least read French.

I’d like to start with one of your last books, Korona-go no sekai (The World After Covid).

That was a long time ago.

Well, it came out at the end of 2021.

In the meantime, I must have published 20 more books.

Is that true? When I checked the information on the Internet, that book was the last one listed.

You see, on average I produce about ten books a year. Well, of course, some of them take the form of a conversation with other authors or are the result of a collaboration, but I write constantly, every day, for my blog, and a lot of those pieces are then collected into book form. The same applies to The World After Covid. It’s not that I planned to write a book about the coronavirus. I did write many essays and articles on that subject for various media, and my editor put them all together and came up with the title. At that time, the pandemic was almost over, and the world had changed quite a bit in the previous couple of years. There was an interest in how to restore the system to its original state or change it to something new, so the time was right to publish such a book.

Of course, the effects of the pandemic are still being felt to a large extent. How have the Japanese been affected by the coronavirus?

Oh my, that’s a really big question. The fact is, we don’t know whether the Japanese government’s coronavirus countermeasures were successful or not. When it comes to success or failure, there are numerical targets, and if you reach them, you can safely say that your policy was successful. Numbers are very useful because they give us a clear picture of the situation. You can make comparisons with other countries. What was the death rate per 100,000 people? How did the medical system fare under pressure? What vaccines worked best? You can compare everything. However, the Japanese government has never summarized its Covid countermeasures. Moreover, they never said whether they had succeeded or not. Instead, they said, we tried our best; we worked hard. So once you declare you did everything you could, all the rest is excused. They worked hard. Never mind the coronavirus countermeasures failed in many ways.

The biggest failure, though, was in the way the inherent shortcomings of Japan’s system came to the fore. The crisis, in other words, made those shortcomings more visible. In the end, the pandemic was a missed opportunity. I think the Japanese system could have been fixed and could have worked a bit better if the flaws that emerged at the time had been corrected one by one.

The worst thing of all, of course, was holding the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. They decided they had to hold the Olympics by whatever means necessary, so they started saying that the coronavirus was not a big deal and looked just like a cold. They needed to create that kind of mood among the people, so in the beginning the government took the lead in spreading anti-mask and anti-vaccine campaigns and telling people not to be afraid. As a result, we had a lot of infected patients and a lot of deaths. You just shouldn’t hold such an event in such circumstances. In the end, there were no spectators, but holding such a festival in the middle of a global pandemic cost an incredible 3 trillion yen. If we have that kind of money, shouldn’t it be used to improve the medical system?

But at that time, the government thought they had to prioritize The Olympics, so they poured a ridiculous amount of money into the festivities, with the usual consequent scandals. Not only were people at Dentsu [Japan’s largest advertising agency] arrested, but opaque money deals happened everywhere, then the Olympic Committee suddenly disbanded before any investigation took place, so all the books disappeared. To this day, we don’t know what all that money was used for. So again, the Tokyo Olympics came to an end without a clear report of whether it had been a failure or a success. Now it’s four years since 2020, and during these four pandemic years, Japan hasn’t been able to come up with suitable policies for social and economic recovery. Added to this, the bad things about the Japanese system are becoming more and more widespread.

From the beginning of the pandemic, the whole world went through a kind of crisis at the same time, and it was a really good opportunity to see how each government dealt with it, to objectively compare which countries’ governments did a good job and which failed. However, the Japanese government refused to show what concrete measures it undertook. They didn’t do any research, they didn’t evaluate the results of their policies; they just forgot about it and moved to the next thing on their agenda, which is the Osaka Expo.

In Japan, it seems that the approach of trying your best rather than producing results seems to be popular.

That’s right. They not only fail to verify the results, but they don’t even set a goal in the first place, whether it’s a numerical goal or something different. They don’t make such plans. This has been going on since the 1930s. It’s a disease that has lasted for 100 years.

What other shortcomings has the pandemic exposed in the social system?

The most important thing is that Covid is an infectious disease, so it’s a scientific, medical problem. In normal circumstances, medical experts get together, discuss the issue at hand, decide what to do, and then the government follows their advice. Basically, it’s a scientific, not a political issue. However, in the end, it wasn’t science that took the lead in Japan but politics. Various scientists expressed their opinions, and the government only listened to and spread the opinions that suited politicians, suppressing everything else. The term “politically led” has been used often for about ten years, and while being politically led is by no means always a bad thing, in Japan, it can be when it comes to issues such as nuclear power plants and the current coronavirus pandemic. That is, politicians only pursue their own interests.

What sectors are you more worried about?

The most sensitive sectors are health care, education, food and energy. For example, in the case of rice and food, they keep saying that Japanese rice and vegetables are already too expensive, so they tell farmers to reduce the amount of acreage because their products won’t sell, or they should stop farming altogether. As a result, Japan’s current self-sufficiency rate is 38%. That’s according to the government’s data. However, according to Professor Suzuki, a food expert at the University of Tokyo, Japan’s actual food self-sufficiency rate is only 9%. It’s fallen that far. Three days ago I was invited to the National Diet to serve as a witness and I heard that if this situation continues, if something goes wrong and the supply chain is disrupted, in the event that the country is cut off or unable to import goods, Japan’s stockpiles will only last for one month. That’s why we are so vulnerable. Yet some politicians say not to worry because we can rely on the market and buy cheap food from China or Brazil.

In European countries such as France, the government is giving a huge amount of aid to agriculture, and not only is the country self-sufficient, but it has enough food to export some of it. Moreover, food safety is high on those countries’ agenda. Japan has no concept of food security.

Even when it comes to energy, there is no concept of security at all. Regarding nuclear power plants and what happened in the 2011 nuclear accident, they’ve continued to cover up everything, and in the end, the proper data have not been released. Also, what will happen next? What will be done about the entire process leading to the decommissioning of the nuclear power plant? That’s another mystery. This is really a scientific topic, and scientists keep saying that it has nothing to do with ideology, profit or loss, or the market. But instead of listening to what they had to sa, and then making policies based on that, the government’s only goal has been political survival – how to overcome the crisis and remain on top.

Other areas where politics, ideology and the markets should not be involved are health care and education. Medical care is meant to protect the health of the people, and education is supposed to be a stable system that supports children as they mature into proper citizens. Those sectors should be managed by the state and given top priority. Instead, they are increasingly privatizing and leaving them to market forces. Essentially, for quite some time, the government has been handing over to private businesses more and more of the things that should be protected and managed by the country itself. We have long been accustomed to entrusting matters to the private sector, starting with the privatization of the Japanese National Railways (1987), and now with the privatization of the water supply business. In places like Osaka, they are closing down public schools, giving support to private education and forcing everyone to attend those schools. They have completely allied themselves to market forces.

Neoliberalism, as we call it, has been rapidly accelerating and strengthening in the past few years, from the second Abe administration, then Suga, and now the Kishida administration. I’ve been saying for quite some time that the country is becoming more and more broken and the State is no longer doing anything about it. It has become obvious that instead of prioritizing the health, safety and happiness of the people, they are now prioritizing the maintenance of their own government. Japan is a corrupt country. It feels like we are nearing the final phase of corrupt dictatorial regimes, such as the Marcos regime in the Philippines and the Suharto regime in Indonesia.

This country is now profoundly sick. If you look at the current scandal about slush funds, most of the important issues are decided by the cabinet without deliberation in the Diet, and any major security changes are made by cabinet decisions alone. We need to have a national discussion about all this. Furthermore, Japan’s most serious problem right now is population decline, but this is not being discussed at all.

Interview by Gianni Simone

To learn more on this topic, check out our other articles :

No141 [FOCUS] Japan as seen by Uchida Tatsuru – 2/3

No141 [FOCUS] Japan as seen by Uchida Tatsuru – 3/3

Follow us !