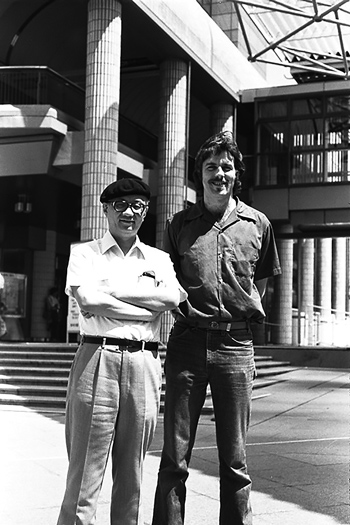

In February 2024, Mariya Marie and Moriyama Megumi published a book in which they describe their ‘spiral translation’ work./ Benjamin Parks for Zoom Japan

With their re-translation from the English, Mariya Marie and Moriyama Megumi have broken new ground.

Many people have tried their hand at translating The Tale of Genji into modern Japanese, among them such literary greats as Yosano Akiko and Tanizaki Jun’ichiro. However, until now, nobody had attempted the kind of approach that Mariya Marie and Moriyama Megumi chose. Sidestepping the original Japanese text from the 11th century, the two sisters focused instead on Arthur Waley’s English translation of Murasaki Shikibu’s novel, translating it back into modern Japanese through a creative process that draws on different sources, both ancient and modern, which the sisters call ‘transcreation’.

Mariya and Moriyama share a long love affair with Western literature. Elder sister Marie is a haiku poet and critic who graduated from Keio University’s Faculty of Letters, Department of French Literature. Megumi, on the other hand, graduated from the University of the Sacred Heart’s Department of English Literature. She is also a poet and has translated Virginia Woolf’s The Waves into Japanese. Their four-volume translation of Waley’s Tale of Genji won the Donald Keene Special Award.

“Arthur Waley published his translation in six instalments between 1925 and 1933,” Moriyama says, “and thanks to him, The Tale of Genji spread throughout European culture because subsequent translations in other languages were based on his version. We wanted to create a work that took advantage of the influence of British culture on Waley’s translation, so we used a lot of katakana [one of Japan’s two syllabic alphabets] and furigana [a reading aid added to clarify pronunciation].”

“For example, Waley translated the Japanese word fue as flute, and tatebue as flageolet,” Mariya says. “In our version, we kept the English words, writing them in katakana. In this way, the reader can understand how Waley expressed the world of The Tale of Genji in English.”

“We even wrote people’s names in katakana,” Moriyama adds. “For example, Genji is originally written 源氏in Japanese, but we wrote it ゲンジ. In a sense, we created a double image, a multi-layered portrait of Genji’s world.”

“Japanese readers who have studied the classics,” Mariya says, “are used to an old Japanese vocabulary that refers to how people in the Heian period spoke and what clothes they wore. However, by adopting Waley’s terminology (e.g. ‘long rob instead of a kimono) and using katakana, we have shaken up the story and, in a sense, made it new. I would say that by reading our version, readers are transported to another world and time, which is neither completely Japanese nor European but a fusion of the two cultures.”

Moriyama Megumi and her sister Mariya Marie provide a new reading of The Tale of Genji. / Benjamin Parks for Zoom Japan

The two sisters have even coined a new term for their work: ‘spiral translation’. “According to German philosopher Friedrich Hegel, history is not circular, that is, it does not return to its origins, but rather evolves and unfolds in a spiral,” Mariya says. “We thought the idea of a spiral was not only interesting but was an apt description of what we were doing. After all, instead of just going back and forth between Japanese and English, we wanted to create an evolved version of Murasaki’s story. That’s when we came up with the term ‘spiral translation’.”

“Words are alive and stories are constantly moving,” adds Moriyama. “Our Tale of Genji features various cultures and languages, and should be read as something new and alive that is perfectly suited to our modern times.”

Asked about how the project came about, Mariya says that it was the culmination of their long love affair with Murasaki’s work. “We have always liked The Tale of Genji since we were very young,” she says, “and we loved Waley’s translation. I majored in French literature, and I later realized that Waley’s style was similar to Marcel Proust’s. Waley’s English translation is poetic and psychologically insightful. We read another English translation of The Tale of Genji, but we found that it was very different. Waley’s writing is clear, elegant and poetic, so for those of us who create poetry, it’s the best possible rendition of Murasaki Shikibu’s work. That’s why we decided to translate it back into Japanese. In the beginning, we thought a short version would be fine. However, we talked to an editor about our project and were asked if we would like to translate the entire book, to which we promptly agreed.”

Moriyama says that when she studied Virginia Woolf in graduate school, she was surprised to learn that there was someone in her literature and art circle, the Bloomsbury Group, who had translated The Tale of Genji. “I only read part of Waley’s version at the time,” she says, “but I thought it was written in an evocative style, similar to Virginia Woolf’s. The other thing that convinced me to tackle this project is a wonderful book called Murasaki Mandala by a Jungian scholar named Kawai Hayao. This book had a great influence on me, but for a long time I wondered how we could approach the story. After all, there were already many translations, and we are not researchers. Then, we realized that by translating Waley’s work we could breathe new life into The Tale of Genji.”

From the beginning, the sisters had a clear vision of what they wanted the writing to be like, and they were unwavering in the way they pursued their goal. “Waley skilfully incorporated British and European culture and customs into his translation to make it easier to understand for British readers at the time,” Mariya says. “The characters are all full of life, wearing long dresses, galloping in horse-drawn carriages, talking about love with a glass of wine in their hand, composing songs and crying their hearts out. He also quotes Romantic poetry, Shakespeare and the Bible. However, the emotion of the original Japanese text is not lost at all.”

“First and foremost, we wanted to convey in beautiful modern Japanese the emotions of The Tale of Genji,” Moriyama says “We wanted to create a fresh writing style with a sense of tension and dynamism. For us, Waley’s work is the most literary and wonderful English translation of The Tale of Genji. Although it is sometimes misunderstood as a parallel or abridged translation, Waley’s genius was to translate the story into English without betraying its original charm and atmosphere. This is an amazing achievement.”

Trying to be as faithful as possible to the novel’s original atmosphere, the sisters had to think hard and choose each word one by one in what turned out to be a long and exhausting process. For instance, when pondering how to best translate the English ‘Emperor Kiritsubo’ back into Japanese, they first considered the more common Japanese terms for the emperor, like Kotei and Mikado, but eventually chose the katakana エンペラー (enperaa) because it added an extra layer of exoticism and was more faithful to Waley’s idea of blending Japanese and Western cultures.

“When people hear the word ‘translation’, they generally think of it as a simple process of transferring words from one language to another,” Moriyama says. “I won’t go into so-called ‘translation theory’ here, but I don’t think that kind of reasoning applies, at least not to literary works. This is because each word has its own history, and cultural and linguistic background, and there is a kind of conflict in replacing words from one culture to another. Even a seemingly simple word has many connotations and it can be difficult to agree on its real meaning. Choosing one translation always means discarding all other available words. Creativity comes into play when we strive to express a certain atmosphere and start pondering the background of the many words and expressions available to us.”

“Waley was criticized for his arbitrary translations,” Mariya says, “and he did omit a few parts of the novel and sometimes, more than just translating the text, he adapted it to his own Western, British sensibility. However, he strongly objected to such criticism, saying, ‘I’m not translating legal documents. I’m translating literature. When I translate literature, I have to convey emotion.’ Like Waley, we have approached this work thinking of it as a literary re-creation. In order not to lose that flavour, we’ve paused to consider every word and sentence, and have moved forward step by step.”

It took three and a half years to finish the translation, working ten hours a day, almost every day. In the end, their work amounted to 2,760 pages, which were divided into four thick volumes. “We’re often asked what difficulties we had with the translation, how we divided our work, and if we ever fought over words and meaning,” Moriyama says. “At first, each one of us translated different parts of the book, according to our personal taste. But in the end, we both ended up translating the story in its entirety, and then we compared each other’s versions, suggesting changes, making corrections, until we arrived at a unified translation that satisfied both of us.”

“People are surprised when we say that we never fought,” Mariya says. “I guess that’s because we’re sisters. I guess in order for the two of us to complete our mission, there was no space for arguing. Even though the translation was difficult, we always talked until we came to an agreement. If we weren’t sisters, I don’t think we’d have been able to understand each other so deeply and help refine each other’s writing.”

Talking about The Tale of Genji’s appeal and why it endures to this day, the sisters mention the complex quality of its plot and the way its many subtle changes slowly unfold. “It’s filled with delicate psychological depictions,” Mariya says, “emphasizing feelings toward nature as well as the uncertainty of things and the fragility of life. It’s spiritually deep and full of melancholic lyricism. While translating this book, we’ve also come to realize that human nature doesn’t change. Laws and customs may evolve through time, but people always fall in love, are happy and sad, and then die.”

“Even though Genji, the Shining Prince, is extremely handsome and has a colourful and intense love life,” Moriyama says, “he gets older and is overwhelmed by sadness, and then he just leaves the scene and the story acquires darker tones. We didn’t understand this side of the story when we read it in our teens. We thought it was really just a love story. However, when we got older and read it again we thought that perhaps Murasaki Shikibu herself was experiencing the same things as she got older. The chapters at the end are deep and quite impressive.”

According to some researchers and commentators, Genji is not the main character of Murasaki’s story, and the real theme of The Tale of Genji is the hardships faced by women in Heian-period society. Even Mariya and Moriyama have stated in previous interviews that “Genji doesn’t give us the impression of a real man. He’s like a hollow vacuum, so we don’t find him attractive as a man.”

“Even the aforementioned Jungian psychologist Kawai Hayao states in his book that this novel is Murasaki Shikibu’s own story,” Moriyama says. “The women who appear are her own alter egos, and though Genji seems to be the central character, the real protagonists – the ones around whom the story actually revolves – are the women who surround him. In this respect, writing the novel was akin to weaving a mandala, so to speak, and through this process, Murasaki Shikibu exorcised her demons and was able to live a new life.”

“To be sure, Genji is a Shining Prince,” Mariya says. “He’s a somewhat mythical figure because he’s popular with women and has many skills and qualities. He’s so perfect that he’s almost inhuman. In that sense, he’s a creature who shines at the centre of the story rather than the main character. All kinds of women surround him in a radial pattern, and Genji casts a light on their joys, sorrows and sufferings.

While creating their ‘spiral translation’, the two sisters kept jotting down notes and comments on their work in progress, which later coalesced into a new book. Lady Murasaki’s Tea Party came out in February and is a sort of critical essay that can be either enjoyed as an introduction or an afterword to their translation.

“This book was another creative collaboration between us, a combination of criticism and creation,” Moriyama says. “We thought it would be useful to describe the process of what we were thinking about and how we interacted while translating the book.”

“We also wanted to present in more detail all the hidden treasure we had discovered in Waley’s text,” Mariya says. “While translating The Tale of Genji, we were so absorbed in our work that we could only see the final goal in front of us. But given another chance to look back at what we had done, we began to dig up again all those half-buried little treasures and to describe them in detail. Each little piece had been a new discovery, and we wanted to present them to our readers. For example, in Waley’s version you can detect traces of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 and Romantic poetry, things like that.

“It became clear,” Moriyama adds, “that Waley was using those hints to help convey to British readers this story from a largely unknown country that a woman had written a thousand years ago. For us, each discovery was extremely exciting, and we tried to convey our intellectual adventure in this book. The Tale of Genji may have been written originally in a small salon of a Heian aristocrat. However, this story transcends time and space and is open to everyone. This story, which spans more than a thousand years, through the ravages of war and epidemics, depicts life, old age, illness and death, and is filled with love.”

Gianni Simone

To learn more on this topic, check out our other articles :

No140 [FOCUS] The Tale of Genji as read and viewed in 2024

No140 [FOCUS] Murasaki, a woman of our time

No140 [TRAVEL] An encounter with flying koi carp

Follow us !