Though housing was apparently less affected, the earthquake has severely damaged agricultural infrastructure.

Tome, nestled in the mountains of Oku-Noto, is a succession of narrow valleys covered with terraced rice fields, with houses scattered along streams and among beech and conifer forests. The imposing wooden houses bear witness to the past wealth of this rice granary. The landscape along the road leading there changes dramatically. Some very damaged villages with ruined houses and crumbling roads, seem abandoned, while others appear to have been spared by the seismic forces.

At first glance, Tome appears to have survived well, its beautiful traditional farms intact with their heavy black tiled roofs glistening in the icy rain. Normally, the region is blanketed with a thick layer of snow in winter, but here too, climate change is turning things upside down: there is very little snow in Noto this year, and it alternates with periods of rain, which melt it away. Further into the village, however, an entire mountainside has collapsed, and the landslide has swept away electricity pylons, so Tome is without electricity and like the whole peninsula, deprived of water, the tremors having damaged pipelines as well as the pumping and water treatment plants.

Shuden Katsuyoshi, a 70-year-old rice farmer oversees one of the two temporary accommodation centres in the village. It’s lunchtime, and low tables are lined up on tatami mats in the main hall. Onigiri rice balls, tsukemono (pickled vegetables) and green tea in plastic bottles are shared by about fifteen people kept warm by a paraffin stove, the atmosphere is relaxed.

The two centres accommodate approximately 70 people. Some of those living in remote parts of the district had to be evacuated by helicopter just after the earthquake, as the roads leading to their hamlets had been destroyed by landslides. The Self-Defence Forces carried out the evacuation to relocate the residents and facilitate relief efforts and food distribution. Mrs Hashizume, an elderly lady who seems a bit forgetful, is happy to be so well looked after in her temporary abode and recounts her adventure. “I wasn’t scared at all to ride in the helicopter, it was like getting into a car!” she says proudly.

Three weeks have passed since the earthquake, and Shuden-san, busy with organizing the centre, hasn’t had time to take a breath, and fatigue is setting in. The first week was the most difficult, without water, without electricity, and with an influx of large numbers of disaster victims. “Luckily, we’ve got rice here,” he says. Once the relief efforts were underway and the families who had come for New Year had left, living conditions gradually improved. The centre had been equipped with chemical toilets, a private company came to install satellite dishes for television reception, and most importantly, generators were installed by Wakayama Prefecture employees who came to provide back-up support. “We could never have managed without them, 60% of the commune’s residents are elderly,” he explains.

When the earthquake struck, the rice farmer was with his family playing with his grandchildren, the youngest of whom was asleep. The child’s father instinctively threw himself over his cot to protect him, and despite the horrendous noise caused by the strong tremors, the shattering glass and the plaster falling from the walls, the baby did not wake up, and the magnificent family home, an immense wooden building built at the end of the Meiji era (1868-1912), remained standing. As it wasn’t snowing, they all spent the first three nights in the cars below the house with the engines running. Fortunately, the telephone continued to work, allowing the villagers to get organized.

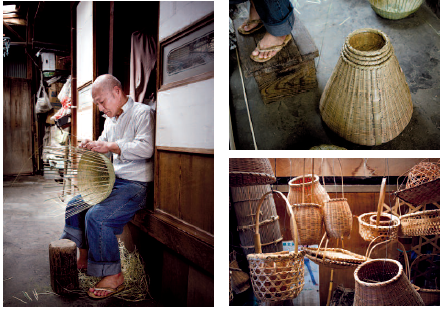

The advantage of being in the mountains is that there are springs, so the village’s water supply was quickly reestablished, reminding the older people of their youth when fetching water was part of daily life and long winter months were spent making traps to catch foxes and rabbits, repairing farm tools, cultivating shiitake mushrooms or making charcoal. While all the houses in Tome withstood the seismic shocks, including the majestic Nakatani family residence, a historical monument from the Edo period (1603-1868), the same cannot be said for the rice fields, the district’s main resource. “We haven’t had time to assess all the damage yet, but the irrigation network has been damaged, terraces have collapsed in many places, and farm buildings and equipment have been damaged. Work in the rice fields usually begins in April, but it’s going to be very difficult to rebuild everything by then,” says Shuden Katsuyoshi. “And then the lack of snow is also bad for rice cultivation, unlike rain that drains through the soil, a blanket of snow protects it and allows it to rest,” he adds.

A few years ago, with about ten other small rice producers, he founded a cooperative, whose symbol is a red dragonfly, to develop the Tome rice brand and promote local culture. They organize farm holidays, have established a small museum of agricultural practices, and build customer loyality by sending them organic vegetables and wild plants. They also have a plan to renovate an old house to welcome visitors who are interested in eco-tourism to the village. But they are all already past retirement age, and these projects are progressing very slowly. As government aid for individuals is only 3 million yen (18,000 euros) in the event of an earthquake, many elderly people will not have the wherewithal to rebuild. “They’ll prefer to leave their villages and join their families in the city,” predicts the farmer. “I want to revive the district development projects that are close to my heart, but the problem is that there are no young people here,” he sighs sadly.

Eric Rechsteiner

To learn more on this topic, check out our other articles :

N°139 [FOCUS] 1 January, Noto Peninsula

N°139 [FOCUS] SHIKA – In the shadow of the nuclear power plant

N°139 [FOCUS] WAJIMA – The tragedy of trial by fire

N°139 [TRAVEL] Osore-zan, a foretaste of hell

Follow us !