For the famous mangaka and director, the view on nature has an almost religious dimension.

Miyazaki Hayao’s work is often defined as quintessentially Japanese, particularly in the way he portrays nature. This is certainly true, though it must be pointed out that his films seldom feature traditionally beautiful scenery, the only exception probably being My Neighbor Totoro.

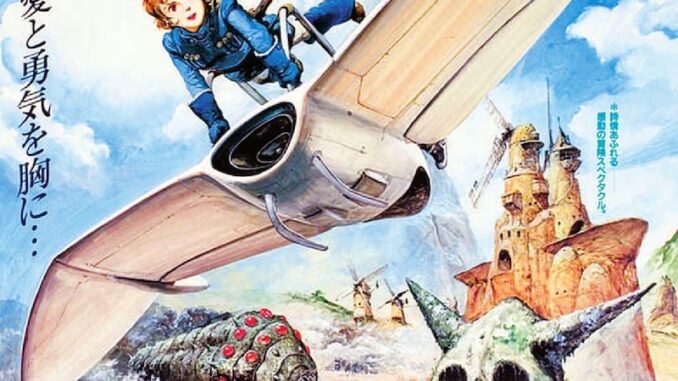

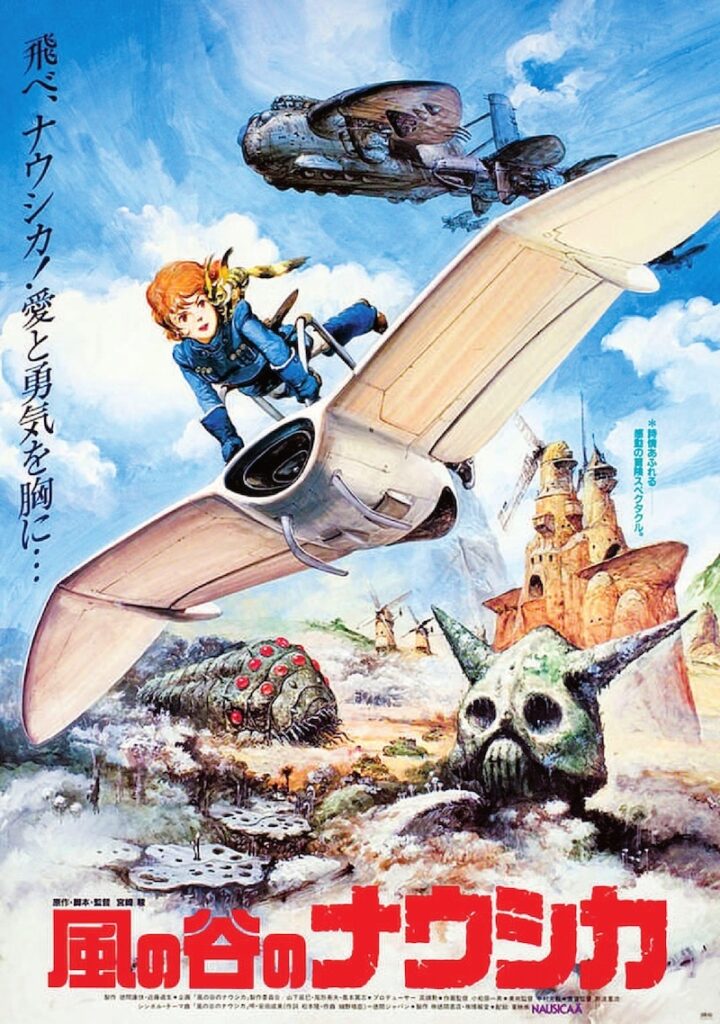

Let’s consider the nature depicted by Miyazaki through Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke.

In an interview titled “Foreign journalists ask Miyazaki Hayao 44 questions about Princess Mononoke” (published in Textbook 10: Princess Mononoke), the director said the following concerning the way nature is portrayed in his films: “I tried to depict not a realistic forest, but a forest that exists in the hearts of Japanese people, a forest that has existed since time immemorable.” The forest “in the hearts of Japanese people” (Nihonjin no kokoro no naka) refers to Japan’s religious faith.

In the August 1997 issue of Seiryu magazine, Miyazaki added that “Japanese gods are neither good nor bad. Sometimes, the same god becomes violent but later shows its quiet, benevolent side. The Japanese have always had this kind of faith. Even though we live in the modern age, we still have the sense that somewhere, deep in the mountains where we have never set foot, there is a dreamlike place with deep forests, beautiful greenery, and pure water. (…) It may be a kind of primitiveness, but even before talking about protecting the natural environment, I see this as our national character. It’s something that we feel deeply in our hearts.”

Interestingly, such words as “mountain,” river,” “plant,” and “tree,” have been in use from ancient times, and flowers and grass are featured in numberless waka and haiku poems. However, until fairly recently, no word collectively encompassed all the natural elements. Only in the second half of the 19th century, after Japan ended its international isolation, was the word shizen coined to translate the foreign word “nature.” So, the word that we take for granted today actually derives from a foreign context.

Accordingly, when watching a Ghibli film, one important thing to keep in mind is that the Japanese view nature very differently from Westerners. In Western culture, nature is the outside world that exists in contrast and relative to the existence of the self. Therefore, our view is based on the dualism of self and other.

On the other hand, the Japanese don’t see nature in dual, conflictual terms. Rather, humans and nature have a close relationship, as if they were part of the same big family, as expressed by the expression “Mother Earth.” In other words, the Japanese approach to nature is not based on opposition but on coexistence. More to the point, humans are allowed to live in nature.

When Europeans climb a high mountain and reach the top, they say they have conquered it and will plant their flag on the peak. On the other hand, a Japanese climber may thank the mountain god for safely reaching the top and leave some food as an offering. That’s because they believe that things also have souls.

Miyazaki also said there was a time in Japan when forests had spiritual meaning. In those days, when you stepped into a forest, you felt a mysterious sensation, as if someone was watching you from behind, or you could hear a sound coming from somewhere. That presence was nothing but a sign that nature was alive, a manifestation of its vitality.

Nature is a central theme in Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke: underground caverns covered in blue crystals (Nausicaä); a beautiful and peaceful forest (Totoro); the divinely shining pond of the Forest Spirit (Princess Mononoke). For Miyazaki, these images of pure nature remain deep in the souls of the Japanese, no matter how economically prosperous or scientifically advanced their country may be.

In Nausicaä, the world’s surface is being invaded by the poisonous Sea of Decay, slowly killing the earth. The poison is what remains of a huge industrial civilization that was destroyed by a war.

In the deepest part of the Sea of Decay lies the Land of Blue Purity, a beautiful land blessed with a pristine forest, pure water, and clean air. Nausicaä can be considered a shrine maiden who governs the Land of Blue Purity.

Referring to this underground world, Miyazaki said that “In the innermost part of our country, there is a very pure place where people should not set foot. There, abundant water flows and protects a deep forest.” We can argue that the director felt that Japanese sensibility towards nature was collapsing, and he wanted to visualize this thought.

In Princess Mononoke, this idea of purity takes the form of the Forest of the Lion God. When Ashitaka first heads to the Forest, numerous echoes appear. These transparent echoes embody the “presence of life” felt by people in the days when forests had spiritual significance.

When Ashitaka is mortally wounded, he is carried to the Forest and immersed in the spring’s waters. Then, the Lion God, who controls life and death, revives him from the dead and breathes new life into him. Miyazaki makes it clear that the Lion God has two sides: life and death, creation and destruction. In the same way, nature brings blessings to humans, but also causes disasters. Nature itself never dies because nature is life itself, it has the power to regenerate, sometimes assuming a different form.

While in the former examples nature is depicted as an unreal, dreamlike realm, Totoro shows a more familiar environment, albeit an idealized one that has become progressively harder to find.

In this story, from the very beginning, as soon as the family moves into their new house, it is repeatedly shown that there is an invisible world next to the real one, and the two worlds run parallel to each other.

Now, let’s think about what Totoro is. Mei first meets the giant creature when she falls into a large tree shrine. Totoro is dozing off, and Mei falls asleep on his fluffy stomach. Later, Satsuki and her father try in vain to find the path Mei took. So, Satsuki’s father tells her she can’t always meet Totoro. Later, Satsuki’s father tells her that the tree’s location coincides with Suitengu Shrine and Totoro owns the tree. In this way, Totoro can be thought of as the spirit of the tree.

It is in Mei and Satsuki’s dreams that Totoro exerts his full power as a tree spirit. When the two see the Totoros sprouting nuts, they rush out into the garden. There, they pray to make the plants grow, and the young shoots rapidly become huge trees. Then the two sisters fly through the sky in Totoro’s arms.

However, the episode doesn’t end there. When they wake up the next morning, they find that the nuts they planted the day before have sprouted. Their dream has become a reality. Overwhelmed with joy, the two girls run around the flower bed saying “It’s a dream, but it wasn’t a dream.” The words they recite are the key to understanding Miyazaki’s thought: reality and dreams correspond. That’s why dreams become reality. In a world where reality and dreams overlap, trees are not just material entities but have life and spirits.

Gianni Simone

To learn more about this topic check out our other articles :

N°147 [FOCUS] Manga and Nature, the Right Stroke

Follow us !

![No51 [MEMORY] A writer who cannot forget](https://www.zoomjapan.info/wp/wp-content/uploads/focus02.png)