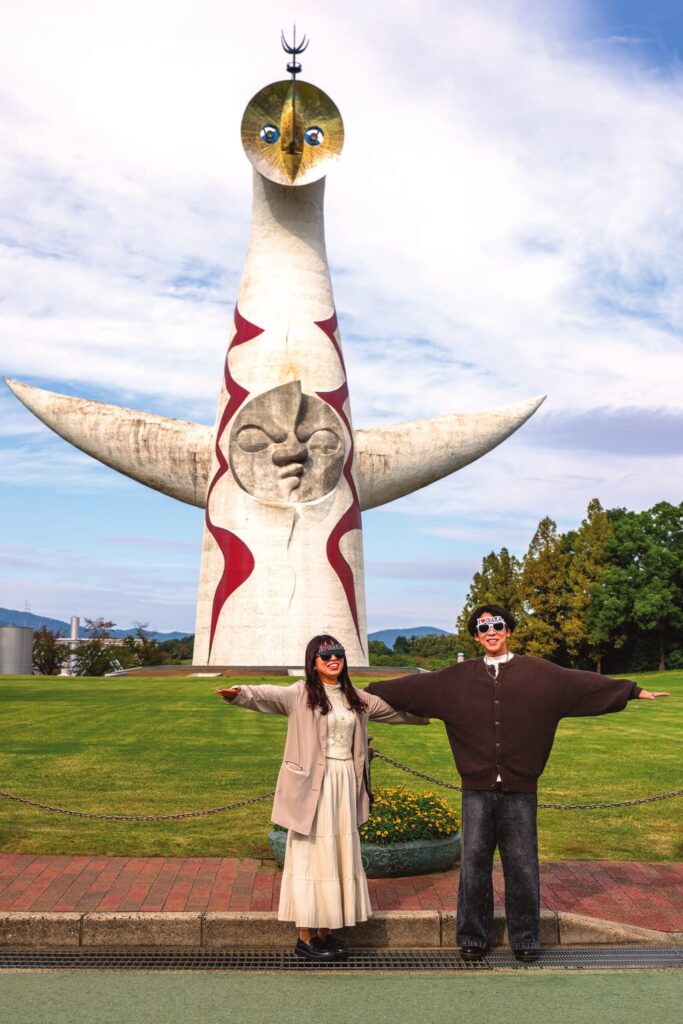

Designed by artist Okamoto Tarô, the monument was supposed to disappear after 1970. It still stands.

If the memory of the 1970 exhibition still survives to this day, it is also thanks to its most iconic work, the Tower of the Sun, which in time has become both the exhibition’s symbol and one of Osaka’s more popular landmarks.

Designed by artist Okamoto Taro as part of the theme pavilion, the tower was planned as a temporary structure that was supposed to be dismantled after the exhibition closed. However, a petition campaign was launched against its removal, and in March 1975 it was decided to preserve it permanently in the exhibition Commemoration Park.

The Tower of the Sun is 70 meters tall, with a diameter of about 20 meters at the base, and features three faces and two arms with a 25-meter span. According to Toshiko, Okamoto’s wife, it represents a crow.

The Golden Face at the top represents the future, the Sun Face on the front torso stands for the present, while the Black Sun painted on the back represents the past.

Three major general contractors joined forces to build the tower using shipbuilding techniques with a steel-reinforced concrete structure. The Sun Face, on the other hand, was made of glass fiber-reinforced plastic to reduce weight. Okamoto was very particular about this face and went to the company’s factory to check on its production, carving and correcting its shape with his own hands. At the time, 3D computer-aided design was not available, and the statue size made it difficult to scale up the original model, so the work relied on the craftsmen’s intuition. The original Golden Face was made of 337 steel plates, but due to deterioration from wind and rain, it was replaced with a second-generation stainless-steel replica in 1992.

Because of the tower’s complex and unique shape, it was initially unclear whether the 70-meter-tall structure would meet earthquake resistance standards or even stand at all, so they had to carry out structural calculations.

The Tower of the Sun was built in the center of the Festival Plaza designed by architect Tange Kenzo, its tip protruding from a large roof made of silver trusses that covered the plaza. When some people pointed out that rain would penetrate through the roof, Okamoto is said to have laughed, and proposed to put a few big fans to blow away the rain.

During the exhibition, the inside of the tower contained a complex display of sculptures and exhibits based on the theme of the evolution of living things, called the Tree of Life. After the exhibition, the tower was closed to the public for 48 years. However, on the few occasions it was temporarily opened, it proved so popular that the City of Osaka finally decided to open it indefinitely.

However, the whole structure had to be first renovated and reinforced against earthquakes. To this end, the walls were made 20 centimeters thicker. In the end, the renovation project was completely successful and even won the 2018 Good Design Award while in 2020, the Tower was registered as a National Tangible Cultural Property. Today, everybody can enter the tower and visit it like 54 years ago. Just remember to make a reservation.

Inside the tower stands a spine-like steel frame called the Tree of Life. It represents a World Tree and is painted in five colors, one for each continent. It can be seen as a description of how life evolved from microorganisms to human beings.

In 1970, 292 models were attached to the branches of the 45-meter-tall tree, some of which were moved electronically. Based on an original idea by Okamoto, the design was created by Narita Toru, known for his work with the tokusatsu SF series Ultraman, and the models were produced by Tsuburaya Productions. In the current version, the number of biological models has been reduced to 183.

In 1970, heavy escalators were installed to speed things up. The exhibition was so crowded that visitors were forced to climb to the top of the tower in five minutes because of the long lines waiting outside. In 2018, the escalators were replaced with stairs and you can now enjoy the exhibits at a leisurely pace.

According to art researcher Ishii Takumi, the Tower of the Sun is an extremely complex work packed with many different concepts and ideas. “Okamoto was thoroughly opposed to the exhibition as an international trade fair,” he says. “He thought that the quest for material progress had caused humanity to lose its pride and dignity, and we needed to recapture them.”

To counterbalance the exhibition’s stress on trade and technology, Okamoto wanted to redefine this event as a sort of sacred festival and erected the Tower of the Sun at its center as a divine statue. Though it was just a reinforced concrete statue, for Okamoto it was like a living thing, and the Tree of Life inside the tower was its blood vessels and nervous system. Therefore, though most people tend to focus on the tower’s exterior look, the Tree of Life can be seen as the true essence of Okamoto’s work.

The Tower of the Sun is a three-layered structure: the underground space is the past, the overground part the present, and the tip of the tower, that originally protruded through the roof, the future. Past, present and future are compressed into one divine monument. “Visiting the inside of the statue is similar to a ritual, like the Shugendo training,” Ishii says, “in which one passes from this world to the next and experiences death and rebirth. In this respect, it also functions as a kind of initiation device. You could say that Okamoto was seriously trying to turn the exhibition into a sacred festival. He wanted the Tower of the Sun, and the World Tree standing at the center of the universe, to be a device to help the approximately 64 million visitors regain their sense of purpose in life.”

An important thing to consider when talking about Okamoto’s work is his encounter with the Jomon culture because the concept of the Tower of the Sun is also related to the Jomon period (between 14000 and 300 BC). Okamoto’s encounter with the Jomon culture dates back to 1951. When he came across Jomon pottery at the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno, Tokyo, he was deeply moved by those prehistoric artifacts.

At that time, Okamoto was concerned that not only in Japan but all over the world, people were losing sight of their original lifestyles, living together with plants and animals, nature and the supernatural, as a result of modernization. For Okamoto, art was a way to reacquire the original way of being; a way to save people from alienation. “I think he was saying that we should regain the wild sensibilities of the Jomon people,” Ishii says. “In any case, Taro felt a strong sense of crisis about the problem of human alienation during Japan’s postwar reconstruction and the years of high economic growth.”

Even today, almost 55 years after the first Osaka exhibition, the Tower of the Sun remains a unique work in the history of the world’s fairs.

Gianni Simone

To learn more about this topic check out our other articles :

N°146 [TRAVEL] A Second Breath in Tohoku

N°146 [FOCUS] Osaka, Land of Exhibitions

N°146 [INTERVIEW] The One Who Knows It Best

Follow us !