Fifty-five years after the 1970 event, Kansai’s capital is hosting its second World Expo.

Universal exhibitions are strange beasts. These events are akin to gargantuan circuses whose goals include showcasing new cutting-edge technology, cultural exchange, and nation branding. They vary in size, scope and global reach, and Osaka has hosted one of the most successful editions ever.

The Osaka Expo was held in Suita City, Osaka Prefecture, between March 15 and September 13, 1970. It was the first world’s fair in Asia and at the time, the largest in history. It was held to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the end of the Second World War and reaffirm Japan’s global success. If the 1964 Tokyo Olympics had symbolized Japan’s readmission into the international community, Expo ’70 showcased the achievements of a country that only two years before had become the second-largest economic power in the world after the United States, experiencing an average annual growth of up to 9% between 1955 and 1973.

Following the equally successful 1964 Summer Olympics, many companies, researchers, architects, and artists were employed to build pavilions, produce video and audio works, and create exhibits. Large-scale projects were made throughout the prefecture in preparation for the event, including the construction of roads, railways, and subways, and the Japanese government spent over 650 billion yen on Expo-related projects.

On the other hand, the mobilization of artists to a national event on a scale not seen since World War II was criticized within the cultural and art world, and university students also launched an opposition movement, claiming that the Expo would distract the public from the debate around the revision of the Japan-US Security Treaty, which was also scheduled for 1970.

Despite the controversies, this gigantic project proved a resounding success, featuring 78 countries and achieving 64.22 million visitors, the highest in the event’s history until it was surpassed by the 2010 Shanghai World Expo (73.09 million). This was equivalent to 60% of the Japanese population at the time. Moreover, although every expo until then had lost money, Osaka ‘70 ended up making a profit of 19.2 billion yen, more than 200 billion in today’s terms.

The real mastermind behind the Osaka Expo was Sakaiya Taichi, a bureaucrat who later became famous as a writer. Then working at the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), he was the section chief of the Expo Preparation Office and led the planning committee (he would also be involved in organizing the sea-themed Expo ’75 in Okinawa). Sakaiya persuaded the political and financial circles, who knew little about the world’s exhibitions, and succeeded in bringing the Expo to his hometown.

The overall design of the Expo site was done by famous architect Tange Kenzo while artist Okamoto Taro was chosen as exhibition producer for the Theme Pavilion, which was considered the heart of the Expo. According to Sakaiya, the selection of the exhibition producer was in dispute until the very end. Then he proposed Okamoto, then 59 years old, whom he had met on a ship to Okinawa and had been deeply impressed by. However, nobody at MITI knew Okamoto, so Sakaiya resorted to something that would probably work only in Japan: he showed his colleagues some old manga works by Okamoto’s father, Ippei. The bureaucrats were so impressed that they finally agreed on appointing the artist, reasoning that “someone unconventional would be good.”

Okamoto was certainly unconventional and a sort of lone wolf in the Japanese art world. His first reaction was to decline the invitation. In the end, after consulting with friends and giving in to Sakaiya’s insistence, he decided to join the project, thus incurring the ire of the anti-establishment students who accused him of supporting state power. However, as soon as he became the exhibition producer, he attacked the Expo’s theme, which was “Progress and Harmony for Mankind.” According to Okamoto, humanity had neither achieved real progress nor harmony.

As the current director of the Okamoto Taro Memorial Museum, Hirano Akiomi writes in detail in his book, Okamoto Taro: The Tower of the Sun and the Final Battle, world expos started out as an international trade fairs and were viewed by many as a sort of cultural Olympics where “each country enlightens the masses under the guise of entertainment. The glittering pavilions, each carrying their country’s message, are there to make Western modernism and globalization look beautiful. Okamoto Taro was against all that. He did not like anything about the Expo idea.”

Of course, Okamoto was right. Indeed, Expo ‘70’s not-so-secret goal was to promote a “standardized mass-produced modern society” in which Japanese products would hopefully be exported everywhere. And indeed, in the years following the Expo, Japanese companies increasingly flooded the world with their high-quality stereos, color TVs, motorbikes and automobiles.

At the Osaka Expo, many goods and services that are now common were either shown for the first time or further popularized, such as sign systems, the monorail, linear motor cars, electric bicycles and cars, videophones and mobile phones. People were amazed by new technologies such as the moving walkway and fully automatic washing machines. Diner-style restaurants (known as “family restaurants” in Japan) and Kentucky Fried Chicken were introduced for the first time. The Expo was also instrumental in creating a conveyor belt sushi boom and turning canned coffee into a global hit.

Going beyond the event’s more flashy and crowd-pleasing features, Expo ’70 succeeded because it aimed for high standards and, in order to achieve them, gathered talent from all over the country. Besides Tange Kenzo, who at the time was teaching at the prestigious University of Tokyo, other architects who were prominent in the event included metabolist Kurokawa Kisho and future Pritzker Prize winner Isozaki Arata. Songwriter Nakamura Hachidai and composer Takemitsu Toru were also involved, while the fashion world was represented by Mori Hanae and Koshino Junko.

In the end, the success of the Expo went beyond all expectations, and the venue was packed every day for 183 days. Due to its extremely crowded conditions, it was even mocked in the press where, thanks to clever puns, Bankoku-haku (World Expo) became Zankoku-haku (Cruelty Expo) and its theme, “Jinrui no shinpo to chōwa” (Human Progress and Harmony) became “Jinrui no shinbō to chōda” (Human Patience and the Long Snake, in reference to the endless waiting lines snaking around the venue).

In some respects, the Osaka Expo has had a lasting legacy. For one thing, the retro-futuristic facility design had a great influence on subsequent exhibitions and events. Half a century after it ended, the Expo is still well known and is often cited as a representative event of Japan’s high economic growth period.

On the other hand, while Expo ’70 was a great success, it left almost no tangible traces. Since a huge deficit was expected, nobody took over the foundation, and all the pavilions were immediately removed. The only landmark that survives to this day is Okamoto Taro’s Tower of the Sun which was only saved thanks to a public campaign. The former locations of older Expo venues, such as the Champ de Mars in Paris and Battery Park in Chicago, have all become famous large parks and tourist attractions, but the site of the Japanese Expo is a huge but lonely-looking park.

Another factor to keep in mind is that since the 1970s, under the initiative of the bureaucracy, Japan’s economic and cultural scenes have become increasingly centralized and Tokyo keeps attracting all the big companies and talent, to the point that Osaka, once Japan’s economic and trade capital, has become increasingly marginalized. Indeed, the headquarters of large companies, both Japanese and foreign, together with publishing houses and the press are concentrated in Tokyo, and cultural figures such as actors, architects, designers, and manga artists move to Japan’s capital. As a result, Osaka’s high-class image, which flourished through commerce and industry during the Edo, Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods, has been lost and the once prominent cultural role of the Kansai region has declined.

Can this negative trend be reversed? This is one of the goals of the people who are behind the second Osaka Expo (the third, if we add the 1990 International Garden and Greenery Exposition) that is scheduled to be held from April 13 and October 13, 2025. The event is expected to attract 28 million visitors and renew people’s interest in the region.

More importantly, the project aims to turn the site chosen for next year’s Expo (Yumeshima, a reclaimed artificial island that for years was just a vast vacant lot and container terminal) into an integrated resort (IR) with hotels and casinos that hopefully will both have a great economic impact and increase Osaka’s cultural and tourist appeal.

In 2017, Sakaiya Taichi, the above-mentioned mastermind of the 1970 Expo, wrote an article for the April issue of Fujin Gaho magazine (the Osaka special edition). “What I hope for,” Sakaiya said, “is for Osaka to host the World Expo in 2025 and build an integrated resort (IR), especially one that can disseminate information. The media is only worried about casino-related gambling addiction, but the IR complex will be more than 80% filled with theaters, international conference centers, hotels, and exhibition and commercial facilities that will serve as show business bases. It will attract tourists from both within Japan and overseas, and is expected to have a high economic and cultural effect, as well as foster high-level production and directing skills.”

However, the 2025 Expo has its share of detractors as well. For example, art researcher Ishii Takumi is concerned about how the organizers are handling the event. “When I read the Master Plan for the 2025 Osaka Expo,” he says, “I found that its major theme was “Designing a Future Society Where Life Shines,” and three sub-themes: “Saving Lives,” “Empowering Lives,” and “Connecting Lives.” I think these concepts are close to what Okamoto Taro wanted to express with the Tower of the Sun in 1970. However, when I watch the news, I wonder how seriously the people involved in the Expo are planning to express those concepts.

“For example, there is a lot of talk about the construction of the Great Roof Ring, one of the world’s largest wooden buildings. However, what kind of approach have these people developed toward the wood they used to build the Ring? Modern people only see wood and stone as materials, but trees are living things. The Expo’s Ring is a structure that was built by taking the lives of living things. The concept of the Expo is touted as “Life Shines” and “Saving, Empowering, Connecting Lives,” but whose life is that?

“Okamoto was enamored with the prehistoric Jomon period. In hunter-gatherer cultures, even objects were perceived as living things. I wonder if there was a dialogue with the trees that were cut down. In other words, I think it’s pointless to express “life” only in form while remaining anthropocentric. If we don’t respect nature, if we don’t have a deeper dialogue with it, the Expo will end up being just a facade.”

Gianni Simone

photo caption:

“Designing the society of the future, imagining our life of tomorrow.” This is the central theme of the event, which will open its doors on April 13, 2025.

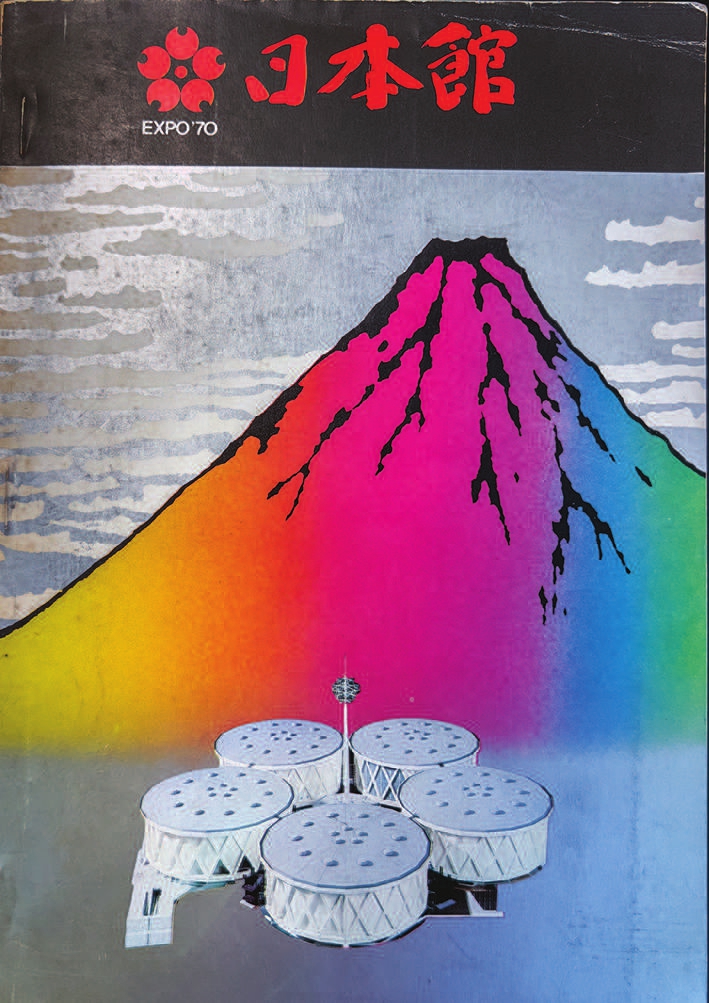

The Japanese Pavilion at Expo ’70

So far, the promotion for the 2025 World Expo has remained low-key.

To learn more about this topic check out our other articles :

N°146 [FOCUS] The Tower of the Sun still shines

N°146 [TRAVEL] A Second Breath in Tohoku

N°146 [INTERVIEW] The One Who Knows It Best

Follow us !