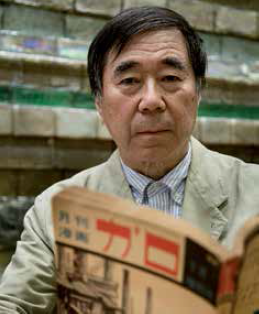

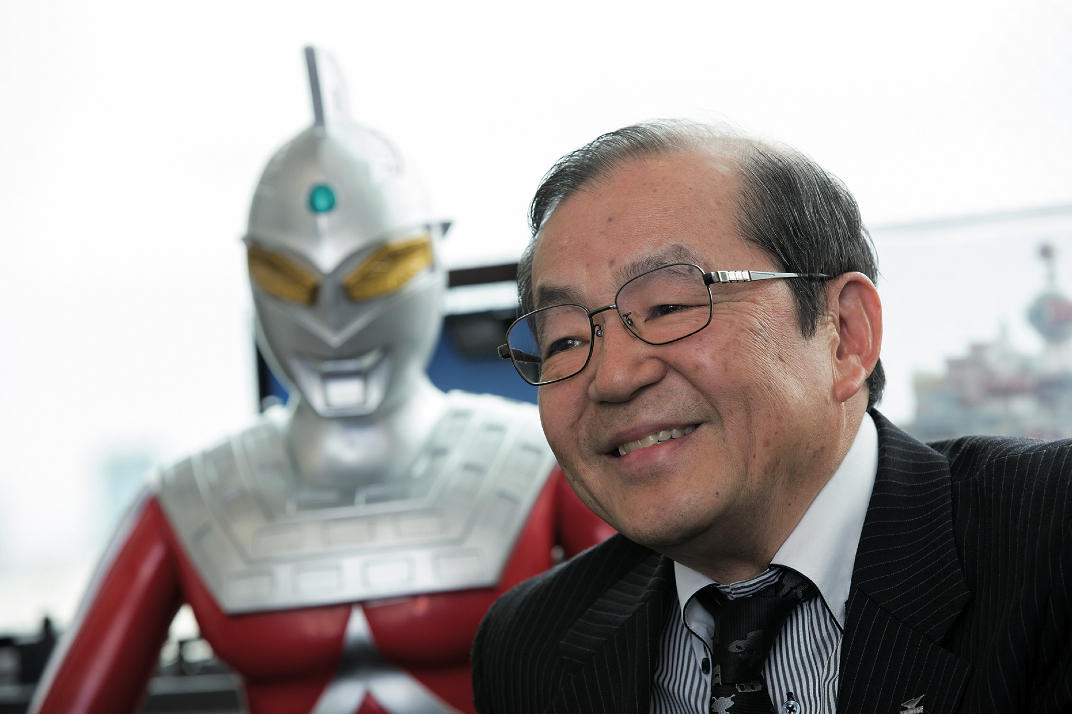

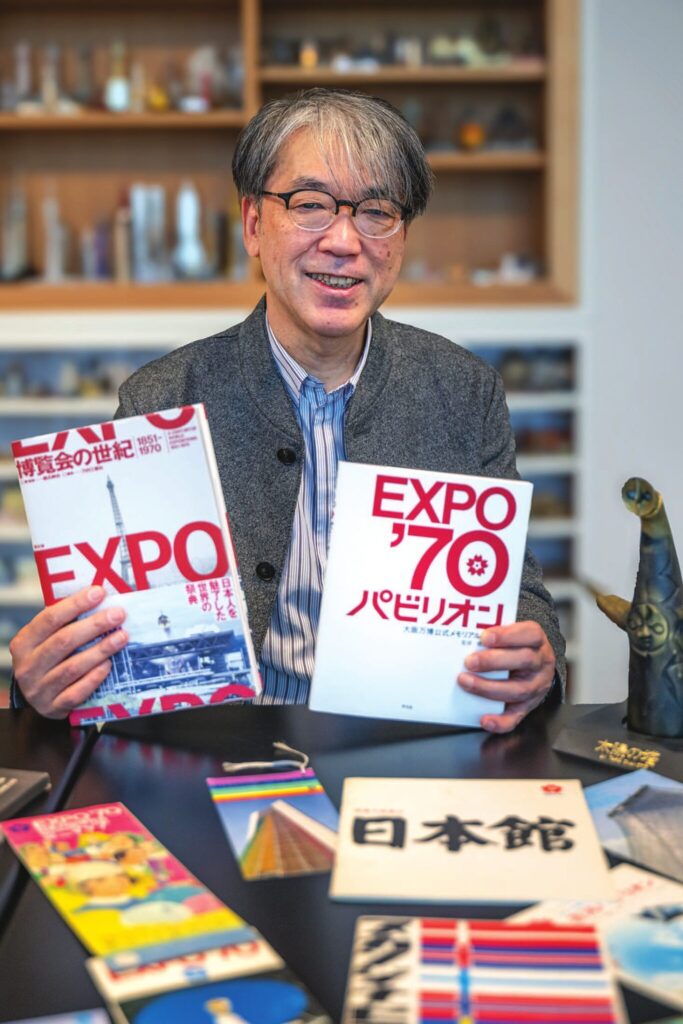

Having visited the 1970 Expo 18 times, Hashizume Shin’ya hopes the 2025 event will achieve the same success.

What did exhibition ’70 really feel like, and how does it compare with the upcoming new exhibition? We asked Hashizume Shin’ya, an architectural historian and urban planner who teaches at Osaka Municipal University and has published several books about the Osaka exhibition. An expert in urban policies and culture in Osaka and the Kansai region, Hashizume is active as a member of local government committees and advisor to urban development-related organizations. In 2007, he also ran as an independent for the Osaka mayoral election on the platform of recreating Osaka through a “generational change.”

exhibition ’70 can be seen as the culmination of post-war reconstruction and economic development. How did Osaka change after the war, and what was the atmosphere like in the city before and during the exhibition?

Hashizume Shin’ya : Osaka was reduced to a burnt wasteland by American air raids. After the war, the city began to rebuild as Western Japan’s main center. At that time, many people moved to Osaka, especially from the nearby prefectures. My father, for example, came from Mie and my mother from Kyoto. My maternal grandparents were from the Noto Peninsula, the same area where the earthquake occurred earlier this year. Like many other people, even my parents thought they would have a better chance in life if they went to Osaka, so my father started a company there. That’s why I was born in Osaka.

Before the war, Osaka was Japan’s industrial and manufacturing capital, and during the postwar reconstruction period, it was rebuilt once again as an industrial center. The city was full of hope and vitality during the 1950s and ‘60s.

I was ten years old when the exhibition took place. At that time, there were still a few vacant lots left, remnants of the city that had been burned down in air raids. Many roads were unpaved, and there was a lot of smoke and car exhaust. Sanitation was not very good. There was a canal near my house. Dirty factory wastewater flowed into it from upstream. On the other hand, many things were changing for the better; new buildings began to be erected one after another, and there was a lot of optimism for the future.

Amid all those changes, organizing the exhibition and attracting people from around the world became our shared mission. They built highways and subways, the port was further developed, and Osaka Airport became an international hub. Even a child like myself felt an electrifying atmosphere all around me during the exhibition.

I imagine you visited the exhibition, too?

H. S. :I went 18 times! You see, our relatives often came to stay over, and company presidents, my father’s clients, sometimes also stayed at my house. Everyone wanted to visit the exhibition, and every time they took me with them. It was such a great experience. I collected pamphlets, badges, and stamps, and whenever I saw a foreign attendant, I asked for his autograph. I was really into it. It was fun, but it was very, very tiring because it was so crowded. It had been planned for 30 million people, instead it ended up attracting 64 million. It was exhausting. Many people went to the exhibition, but I wonder how much they actually managed to see because the waiting lines were unbelievably long. Getting into the popular pavilions was especially hard. I think I went to the American Pavilion twice to see the Moon Rocks, but you couldn’t just stop and look at them. You had to keep moving and I probably only spent about ten seconds in front of them.

At the time, how was the popular mood about the exhibition?

H. S. :It was the first time for Osaka to hold such a huge event, and there were slogans affixed all over the city, even on the counters of my father’s company, saying “Let’s make the Osaka exhibition a success.” That became our goal. As we returned to the international community after losing the war, everyone was proud to be a Japanese and an Osakan. When I researched the exhibition in later years, I found out that there was a lot of confusion and not few problems, such as construction being delayed and money not being raised, but I was just ten years old at the time and all I could see was people being united by a common effort to succeed.

Do you mean that nobody opposed the event?

H. S. :Actually, at that time, there was an anti-exhibition movement. 1970 was the year when the Japan-US Security Treaty was to be renewed, and the students who were against it were also opposed to the exhibition. Another thing is that many creators, artists, and designers contributed to the exhibition, and they were very strict and ideological at the time. There was a lot of political and social turmoil. After all, the Vietnam War was still going on, the Soviet Union and the US were in the middle of the Cold War, and the world was falling apart in the currency market. The exhibition’s main theme was “Progress and Harmony of Mankind” but at that time, there was no harmony in the world, and so-called progress was polluting the planet. So, the message that the Osaka exhibition sent out was that harmony is important, not just progress or development at all costs. I think that message is still very important.

As someone who visited the exhibition 18 times, you got to know it very well. Which pavilions attracted the most attention? Which were the most popular?

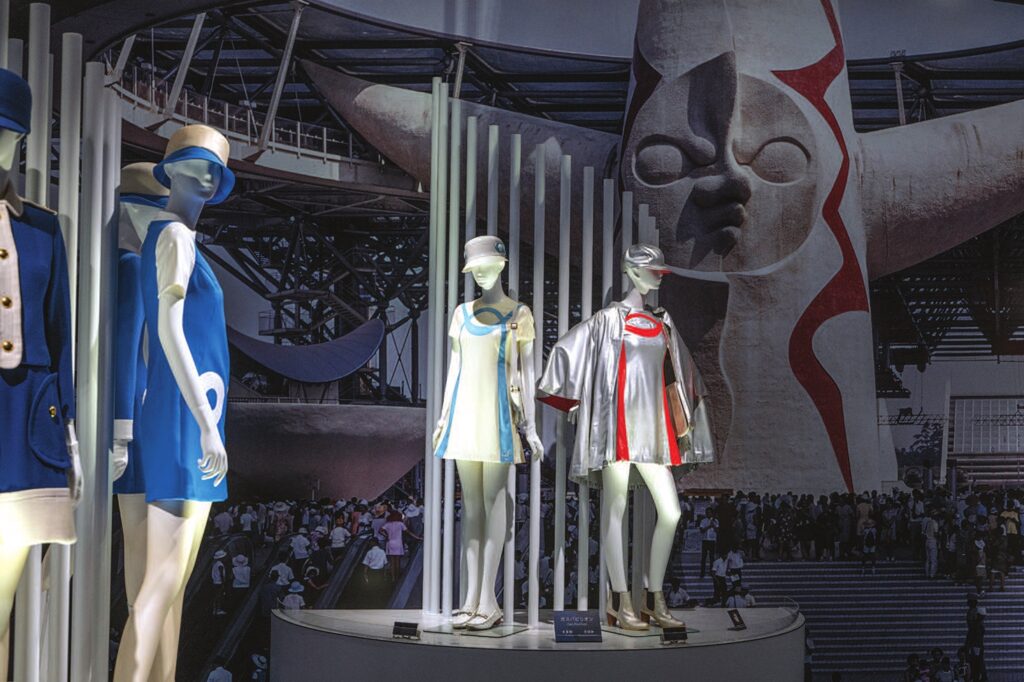

H. S. :I must say that my favorite pavilions were different from the ones everybody wanted to see. The pavilion that I liked the most was the one my father’s company worked on. It belonged to an American company, and I was obviously particularly attached to it because my father was involved. Generally speaking, the American and Soviet pavilions were very popular, and Japan of course. Japanese companies such as Mitsubishi and Hitachi also attracted huge crowds. The exhibition organizers went to see the previous world’s fair, exhibition 67 in Montreal, and learned a lot from them, both from a technical and creative point of view, like how to convey a message by using giant monitors and multi-screens in order to create an immersive space. So what was especially popular with visitors was not as much the content or message as experiencing those things in new ways. At that time, psychedelic design was everywhere, and progressive computer-aided music was just starting to become popular, so everyone was exposed to new music and visuals. For many people it was their first chance to experience such a thing.

Another pavilion that I liked was the Scandinavian one whose theme was “plus and minus.” Their message was that progress and economic development have both a positive and negative side. As industry continues to flourish, the environment becomes polluted and the gap between rich and poor widens. Visually speaking, this pavilion was quite unique and innovative. Visitors were given a piece of paper, on which various slides were projected, and were asked to decide for themselves whether they thought it was a good thing or a bad thing.

An art museum was also set up. Half of the exhibits showed the history of civilization in the West, from ancient Greece and Rome to the present, and the other half displayed Japanese art. The idea was to show that even Japan had produced its own culture and civilization and we should be proud of it. Our country has global appeal and should be valued and respected not only for its economic achievement but also for its cultural contributions. I probably vaguely understood this as a child, but later I realized that Japan was not an isolated nation but a worthy member of the international community.

Another great thing about the exhibition was that each national pavilion had a restaurant. This gave you a chance to sample food from around the world. One day I ate at the French Pavilion and the lunch set came with a baguette, which I’d never tried before. It was probably the first baguette I’d ever eaten and I remember wondering how the French could eat such hard bread.

Perhaps my favorite memory was visiting Thailand’s National Day event and being amazed to see a show where an elephant was engaged in a tug-of-war with a car. I’d seen elephants in cages at the zoo, but it was the first time I saw an elephant in action like that.

In your opinion, what kind of legacy has the Osaka exhibition left?

H. S. :exhibition ’70 showed that these events could become truly global. Until then, only Europe, America and Australia had held a world’s fair. Osaka was the first Asian city to do that. In this respect, it opened the doors to other countries such as Korea and China. In 2010, for example, Shanghai held a World exhibition. It was followed by Dubai in 2020, and Saudi Arabia is going to hold one in 2030. But Osaka ’70 was the real turning point in the history of the world’s fairs.

Osaka’s success inspired other Japanese cities to apply to host World Expos: Okinawa in 1975, Tsukuba ten years later, Osaka in 1990 for the International Horticultural Exposition, and Aichi in 2005. Osaka itself gained a lot of confidence.

The city took on an enormous task and delivered one of the most successful expos in history. Everybody was proud of what they had achieved, and the exhibition put Osaka on the international map once for all. Until then, the only foreigners I had met were those on American dramas on television. But in Osaka, for the first time, 77 countries participated and we were able to interact with people from around the world. So the exhibition became a driving force for the Japanese to become more international.

Even for me, the exhibition was a turning point. Even though I was only a child, I saw everybody being happy and having fun, and the power that such events could have on the people. I decided I wanted to do something like that, and when I grew up I studied architecture and urban design and ended up becoming an expert in entertainment and amusement parks, expositions, and large cultural events.

Next year, Osaka will have another chance to host a World exhibition. How does Osaka 2025 compare with Osaka ’70?

H. S. :Unfortunately, the new exhibition has a bad reputation with the media. Indeed, a lot of money was spent, and the numbers show that relatively few people want to go. Another exhibition was held in Nagoya in 2005, and many people have forgotten what it was like 20 years ago, but even then, it was a rather local event and didn’t become much of a topic in Tokyo or Osaka. The problem is that things have changed and people are not as excited by such festivals as they used to be in the past, especially the younger generations. It’s not like such sporting events as the World Cup or the Olympics which the whole world pays attention to.

Also, as I said earlier, back in the ‘60s everyone wanted to make the exhibition a success. It was a question of pride. My parents’ generation thought that by hosting an international exposition, Japan would be judged by the whole world, and failure was simply not an option. They felt that it was their duty to show everybody that Japan had a rightful place in the international community. Now, however, the new exhibition campaign goes something like “The exhibition is coming, let’s go to the exhibition!” In other words, many people think that it’s not about them. The exhibition has become just like another festival, conceived and created by someone else. It’s just a fun event. And here’s the problem. At an exhibition, each country, each pavilion conveys a message, and I always say that since we are the host country, it is our job as Osaka, Japan, to prepare a place where people can interact and have a dialogue. But the general public doesn’t share that feeling. For most visitors, the exhibition is just a place where you pay to experience some kind of entertainment.

It’s rather disappointing, but I hope that once it starts in April, people’s attitudes will change. The exhibition is a place to interact with the world, a place for us to think about the future of this planet. We should have a more positive, proactive attitude toward it.

You earlier mentioned diffuse criticism toward next year’s exhibition. What do you think about it?

H. S. :I think a lot of it is justified. They say that they spent too much money on this project, that the structure won’t be completed in time, that there was an earthquake in the Noto Peninsula, and reconstruction efforts should be prioritized over the exhibition. All those things are correct. However, Japan has made a promise to the rest of the world, and it is our responsibility to keep that promise. We must show that we are a trustworthy member of the international community.

I have been involved in this project for a long time, and when we first discussed the main theme of the exhibition, back in 2015 and 2016, I strongly emphasized the importance of contributing to the debate about Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Those goals were created by the United Nations General Assembly around 2015, so at the time they were not widely known around the world. That’s why we agreed that the new exhibition’s main theme was going to be “Designing Future Society for Our Lives.” We want to say that we should create a sustainable society.

Then, after that, there was the pandemic that posed a serious threat to our lives, and then Russia invaded Ukraine and another war raged in the Middle East, so I believe that now more than ever, our message is relevant. We all should think that life is precious and we have to do something to protect it. However, many people only see the exhibition as a theme or amusement park, just another kind of entertainment. That’s why a lot of criticism has been directed toward the exhibition. I accept that, and I understand their point of view, but at the same time I get very upset when I see that they only focus on local issues, and in so doing they miss the bigger picture. It’s frustrating when we can’t get our message out.

Interview by Gianni Simone

To learn more about this topic check out our other articles :

N°146 [FOCUS] Osaka, Land of Exhibitions

N°146 [FOCUS] The Tower of the Sun still shines

N°146 [TRAVEL] A Second Breath in Tohoku

Follow us !