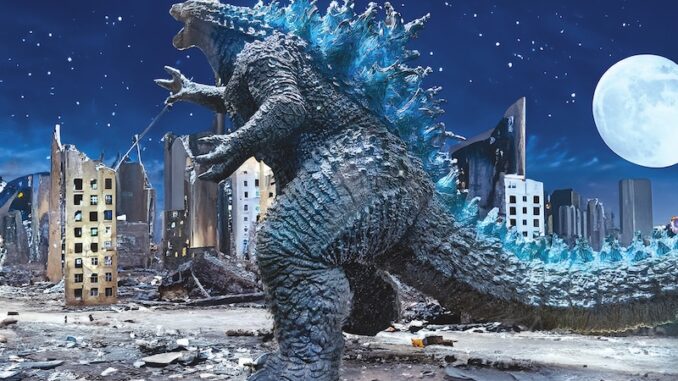

A series of circumstances and a unique context contributed to the emergence of the famous Japanese monster.

In the 1950s, Japan was a country in transition; still dealing with the recent painful memories of the Pacific War, trying to move on, mend the physical and psychological wounds, and regain a place in the international arena. As we will see, it is no coincidence that the original Godzilla came out in 1954. Indeed, its release can be seen as the culmination of a long political and cultural process.

Although World War II had ended nearly ten years before, only recently had Japan regained its full sovereignty. The war had officially and legally ended on September 8, 1951, when 49 nations signed the Treaty of San Francisco. Still, Japan had to wait seven more months for the treaty to be officially ratified. Only then did the Allied military occupation of Japan end.

Japan may have officially regained its sovereignty, but that did not mean it had completely regained its freedom: in fact, on the same day of the Treaty of San Francisco, Japan and the United States signed a Security Treaty that, among other things, gave America the right to maintain military bases on Japanese soil and established what some have called Japan’s “subordinate independence” under U.S. hegemony.

On May Day 1952, only a few days after the treaty entered into force, more than a million people participated in 331 protests across the country. In Tokyo, thousands of demonstrators (among them left-wing groups that were believed to be preparing a violent revolution) clashed with the police in front of the Imperial Palace. Two people were killed, 2,300 were wounded, and 1,230 were arrested.

The May Day protests also opposed the rearmament of the National Police Reserve. Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, which entered into force in 1947, states that Japan will never maintain “land, sea and air forces, as well as other war potential.” Therefore, the American bases in Okinawa and other regions were justified as the only way to defend the country in the case of an attack.

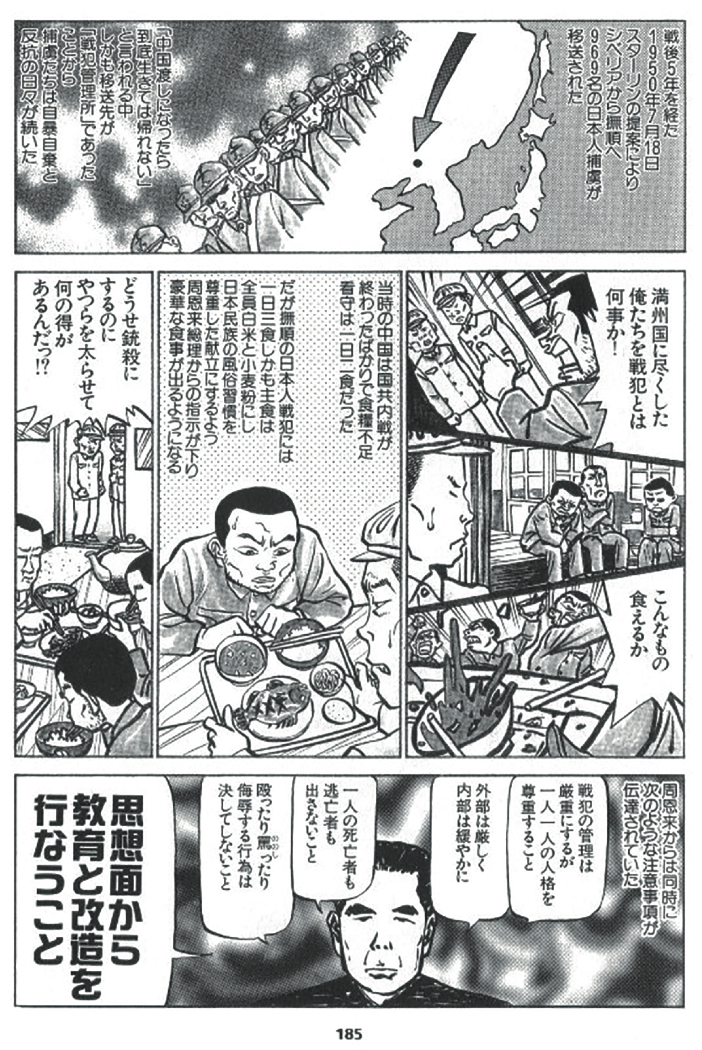

However, when the Korean War broke out in 1950, the 24th U.S. Infantry Division that was stationed in Japan was sent to fight, leaving the country without armed protection. General Douglas MacArthur’s solution to the problem was establishing a lightly armed National Police Reserve. The original 75,000-men force was expanded two years later to 110,000 with the creation of the National Safety Forces, which, in turn, was reorganized as Self-Defense Forces in June 1954.

The Korean War, which ended in 1953, also played a pivotal role in Japan’s postwar recovery. Being very close to the Korean peninsula, Japan became a sort of U.S. frontline base and throughout the conflict, Japanese companies received requests for supplies, weapons, and other equipment from the American armed forces. This demand triggered a period of high economic growth during which the country’s gross domestic product became second only to the United States. As Japan’s living standard improved significantly, a larger portion of the population could afford refrigerators, washing machines and TV sets.

Economy aside, the year 1954 began under bad auspices. On January 2, the Imperial Palace Grounds were opened to the general public, via Nijubashi Bridge, for the annual event in which the imperial family appears on the balcony to greet visitors. It was a sunny day, and more than 380,000 people came for the public audience, too many to be safely handled by the security personnel. By 2:00 p.m. the situation had become chaotic. Then, at around 2:15, an elderly woman who was in front of the crowd stumbled, and people behind her fell on top of her one after another, creating a domino effect. In the end, 17 people died and 82 were injured, some seriously.

There was also trouble on the domestic political front. On February 1, the National Diet discussed a fraud case related to Hozen Keizaikai, a private investment group that at its peak had attracted 150,000 investors by guaranteeing high dividends. It was later discovered that the company’s profits derived not from sound investments but from exploiting the stock market.

Hozen Keizaikai’s bad schemes came to light when stock prices crashed in 1953, causing damages for approximately 4.4 billion yen. It was also revealed that part of that money was used for political maneuvering, and members of several political parties had served as paid advisors. On February 1, one of them testified that prominent Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) members including Hatoyama Ichiro, Ikeda Hayato and Sato Eisaku had received millions in political donations. In the same month, Sato was also implicated in a shipbuilding scandal for which the prosecutors asked for his arrest.

Eventually, Hozen Keizaikai’s chairman, Ito Masutomi, was sentenced to ten years for fraud. Hatoyama, Ikeda and Sato, on the other hand, went on to serve as prime ministers between 1954 and 1972, and Sato was also awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1972.

If many Japanese were dissatisfied with the political elite, there were other things they could cheer for. One of them was professional wrestling. Starting on February 19, former sumo wrestler Rikidozan and famous judoka Kimura Masahiko partnered in a series of tag matches against the Canadian Sharpe Brothers that helped boost TV viewership, with reception contacts surpassing 10,000. The Japanese pair lost that first match, but by the end of the series, tens of thousands of Japanese were fervently cheering for them inside Tokyo’s Memorial Hall and in front of “street TVs” that commercial broadcaster Nippon Television set up in public spaces.

In the 1950s, millions of Japanese saw in pro-wres a chance to avenge the humiliations suffered during the Allied occupation and reaffirm a sense of national pride. In the novel arena of choreographed athletic theater and mock combat that is pro wrestling, Rikidozan quickly became a star – a national hero who thanks to his devastating “karate chops,” beat up much bigger Americans who, according to plan, invariably resorted to dirty tricks. His hard-fought victories exuded a sense of moral justice and made Rikidozan the second most famous person in postwar Japan after the Emperor.

Ironically, this quintessential Japanese figure was actually a Korean named Kim Sin-rak who had first come to Japan to become a sumo wrestler and had suffered discrimination because of his origins. When he obtained Japanese citizenship in 1951, he was given a new identity (claiming he was born near Nagasaki) and all traces of his Korean past were erased. However, his fans could not care less. Rikidozan was fighting on the good side, and the Japanese desperately needed someone or something to help them exorcise the ghosts of defeat.

Those ghosts were still hovering over Japan. On March 1, the U.S. Navy exploded a hydrogen bomb over the Bikini Atoll near the Marshall Islands, containing an explosive power equal to 20 million tons of TNT – more than 1000 times the destructive power of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Some 130 kilometers east of the explosion, a Japanese tuna trawler, the Lucky Dragon No. 5, and its 23-member crew were exposed to nuclear fallout. After returning to port, all crew members were confirmed to have radiation sickness, and one of them died from radiation poisoning.

Public outcry followed as the Lucky Dragon incident was seen as the third time in which the Japanese were victimized by the Bomb. Moreover, more than two months after the tests in Bikini, radioactivity was still being detected in the rain. This led, on August 8, to the creation of the National Council for Signature Campaigns to Abolish Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs.

In the 1950s, radio, cinema, and newborn television (the first regular broadcasts date back to 1953) entertained millions of people while helping them exorcise their traumatic memories of loss and defeat through fictional representations of Japan’s recent past.

Between April 1952 and April 1954, public broadcaster NHK aired the radio drama Kimi no nawa (Your name is?). The show proved so popular, especially among women, that while it was still in progress, the story was also turned into a three-part film (1953-54) that broke all box office records and even sparked a fashion trend: the way Machiko, the heroine, wore her scarf was called Machiko-maki and copied by many women. When the radio show finished in 1954, the drama was then published as a four-volume novel.

The two protagonists, Machiko and Haruki, meet for the first time by the Sukiya Bridge in downtown Tokyo during the U.S. air raid of May 24, 1945. They save each other’s lives and promise to meet again on the bridge exactly six months later. However, while Haruki returns to the spot every half year, Machiko can’t do the same. As in any good melodrama, the plot has many twists and turns, but the heart of the story is that Machiko’s love for Haruki is hopelessly entangled with memories of loss: on the same night that she found her true love, she lost her parents. Only after Machiko is ready to face her past, can she be reunited with Haruki.

Other issues that are featured prominently in the drama, prostitution and interracial children, are also connected to the aftermath of the Japanese defeat. The story never mentions the role played by the occupation forces, but the American influence on the characters’ lives is always there, unavoidable.

The 1950s were also the golden age of Japanese cinema. There were no less than five major companies, with some studios churning out two major releases every week. In 1954 alone, 370 feature films were released, shown in some 7000 theatres and grossing around ¥20 billion. By 1958, the number of moviegoers exceeded 1.1 billion.

Japanese cinema was also being noticed abroad. Kurosawa Akira’s Rashomon won the Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival and Best Foreign Language Film at the 1952 Academy Awards, becoming the first Japanese film to attain significant international reception. Then, in 1954, Kinugasa Teinosuke’s Gate of Hell won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival while Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and Mizoguchi Kenji’s Sansho the Bailiff won the Silver Lion at Venice. That was the third time in a row that a work by Mizoguchi won a prize at Venice. International recognition helped to restore Japan’s cultural pride.

The end of the Allied occupation meant the end of film censorship. This resulted in the return of period dramas, which had been banned by GHQ. Now free to look back at the past war anyway they wanted, Japanese directors made both nostalgic works like Battleship Yamato (1953) and The Eagle of the Pacific (1953) (the latter by the same Honda/Tsuburaya team that one year later made Godzilla) and poignant anti-war meditations such as Kinoshita Keisuke’s Twenty-Four Eyes (1954), and Ichikawa Kon’s The Burmese Harp (1956).

The competition among film companies became so intense that the 1950s are often referred to as the “studio wars” years with each major (Toei, Toho, Shochiku, Daiei, and Nikkatsu) vying for dominance in the rapidly growing market and going so far as to try to poach directors and actors from each other.

Each studio had its own distinct philosophy. Shochiku, for instance, focused on human dramas and family-oriented films, which were best represented by the works of directors like Ozu Yasujiro. Daiei produced a mix of genres but seemed to have a knack for making arty stories with an international appeal, including Rashomon, Gate of Hell and Mizoguchi’s films.

Nikkatsu reentered film production in the 1950s and became known for its action and youth films. Among them, Season of the Sun (1956) and Crazy Fruit (1956) became a social phenomenon known as Taiyo-zoku (Sun Tribe) films while turning young actors like Ishihara Yujiro and Kobayashi Akira into stars.

Created in 1951, Toei was the last born of the major studios and in order to beat the competition, it began to show its titles at local cinemas that were not part of the distribution networks of the long-established Toho and Shochiku. Eventually, Toei gained a reputation for making popular period dramas, and by 1959 had grown to earn one-third of all Japanese film revenues. This studio also led the revival of Japanese animated films and ushered in the era of widescreen films in Japan by introducing Toei CinemaScope.

Toho was one of the oldest and most respected majors and had among its ranks directors of the caliber of Kurosawa and Naruse Mikio. However, it had been recently weakened by a series of union struggles and was looking for new ways to beat the competition.

It was in such circumstances that in 1954 while browsing a film trade journal, Toho producer Tanaka Tomoyuki read about the phenomenal success of an American monster film released the previous year called The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. Featuring stop motion animation by Ray Harryhausen, it was about a prehistoric monster revived by an atomic test. Sensing that monster movies could find a market in Japan, Tanaka convinced other Toho executives to give it a try. He was taking a huge risk but had a lucky break when both special effects expert Tsuburaya and director Honda joined the project.

As it happened, Honda at first was not terribly enthusiastic about making a monster movie. However, he was inspired by the Lucky Dragon incident to use a monster to make a statement on Japan’s wartime experience and the evils of nuclear weapons. Honda even insisted the creature breathe a radioactive ray.

To be sure, America is never mentioned in the film, but Japanese viewers did not fail to see in Godzilla the American atomic bomb or feel the unnamed enemy’s presence throughout the story. Honda, however, avoided a direct reference to the Lucky Dragon incident, only hinting at it in the first scene when a fishing boat is wiped out by a symbolic representation of the Hiroshima explosion.

/ Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

When Godzilla was released on November 3, it was a smashing success, but Japanese reviews were mixed. The critics accused the film of exploiting the widespread devastation that the country had suffered in WWII as well as the Lucky Dragon incident. Also, frustrated by the producers’ reticence in pointing the finger toward American responsibility, one writer insisted that Godzilla should have crossed the Pacific and attacked American cities instead of Tokyo.

Be as it may, by turning the atomic bomb and America itself into a monster (for some observers, even the visiting American pro wrestlers looked like monsters) Japanese popular culture managed to tackle important issues that remained suppressed in political discourse. The sense of loss was transformed into destructive forces that, in the case of monster films, defied human comprehension.

Ironically enough, in a scene that may or may not be intended, Godzilla shows no mercy in trampling Sukiya Bridge, the symbol of Kimi no nawa‘s painful memories. Since appearing in the radio drama, surrounded by a city leveled by air raids, the bridge had become a sort of liminal space; a symbol of Japan’s tragic defeat that kept attracting orphans, shoeshines, and other desperate people. For Machiko, Tokyo may change but Sukiya Bridge will always be the same. Unfortunately, Godzilla does not share her feelings: it arrives only a short time after Machiko and Haruki’s happy reunion and destroys the bridge, somewhat reenacting the scene of wartime destruction from which those memories originally emerged.

Gianni Simone

To learn more about this topic, check out our other articles :

N°145 [TRAVEL] A Quick Trip to Tokyo with Godzilla

N°145 [FOCUS] Fate: Born of an Almost Unknown Father

N°145 [FOCUS] A phenomenon : Forever in our memories

Follow us !