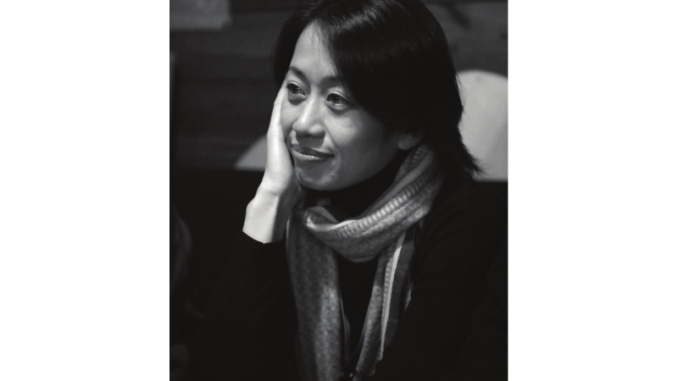

By exploring the island since 2009, Japanese documentarian Sakai Atsuko has learned a great deal about her own country.

Throughout the years, Japan and Taiwan have had interesting cinematic exchanges, but arguably nobody has investigated the historical and cultural relationship between the two countries than filmmaker Sakai Atsuko. A former saleswoman and reporter, in 1998 Sakai left her newspaper job to embark on a long project that so far has resulted in three acclaimed documentaries, Taiwan Life, Taiwan Identity, and Taiwan Banzai. Zoom talked to Sakai about the motivations behind her project.

You have devoted the last 26 years to making your documentaries. How has your approach changed regarding the complex relationship between Taiwan and Japan?

It all started because I’m a big movie buff. In 1998, I saw Vive l’amour by director Tsai Ming-liang. Not only did I love the film, but I found Taipei, where the story is set, very charming and attractive, so I visited Taiwan’s capital in the same year. Another Taiwanese movie I liked a lot was Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A City of Sadness. Since the town where the film was set is near Taipei, I also went there. When I was about to return to Taipei, I was standing at a bus stop when an old man came up to me. He asked in Japanese if I was from Japan, so we talked for a while. The old man told me that when he was a child, he had a Japanese teacher who loved him very much. The teacher returned to Japan after the war, but the old man still hoped to meet him. That was in 1998, and 53 years had passed since the war ended. It was a big shock to me that after such a long time there was someone in Taiwan who was still thinking about hisJapanese teacher. In Japanese schools, we learn in our history textbooks that Taiwan was once a Japanese colony, but of course, we never learn about the lives and feelings of the people who lived in Taiwan at that time. When I met the old man, I felt a surge of anger both at my own ignorance and the country that had failed to educate me on such matters. When I got back to Japan, I was able to channel that anger in a positive direction, to make a film that would convey my experiences. In other words, I made Taiwan Life to convey to the Japanese the voices of the old men and women who had experienced Japanese colonial rule.

As I listened to the stories of all those old Taiwanese, I realized that they had experienced both good and bad things during the colonial period. Furthermore, I heard they had a hard time even after Japan lost the war and left. I wanted to know more and to depict the postwar period of the Kuomintang dictatorship, from the February 28 Incident to the so-called White Terror. That’s how TaiwanIdentity was born.

Then, of course, I wondered how the Taiwanese people were able to overcome those turbulent times before and after the war. I wanted to find the source of their strength and resilience. Next time, I went south of the island to make Taiwan Banzai. The reason why I went south is because I thought I would find there, away from the big cities, the real Taiwan. Originally, this island was home to hardworking farmers and fishermen whose lives are rooted in that land. To me, their strong connection to the island was why Taiwan’s history hadcontinued unbroken for so long.

To go into a bit more detail, every film features an indigenous person. There are currently 16 indigenous people in Taiwan, recognized by the government. The total population of Taiwan is about 23.5 million, and the total number of indigenous people is about 590,000. That’s only 2.5% of the total population. However, when you think about the long history of Taiwan, the people who have lived there since the beginning, though few, have a history of accepting various foreign people, such as immigrants from China, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Japan. In my opinion, this is the source of the Taiwanese people’s tolerance, strength, and flexibility.

It is said that the relationship between Japan and Taiwan is still quite complicated – a mixture of good and bad feelings, friendship, respect and resentment. What do you think about this?

There is an old lady who appears in Taiwan Life who compared this situation to”unsolvable math.” I find this definition aptly describes the relationship between the countries very well. The generation that directly experienced Japanese rule has rather complicated feelings toward Japan. The next generation, that is, their children’s generation, lived in a time when the ruling party, the Kuomintang, imposed a dictatorship, so it was a time when anti-Japanese education and propaganda were a given. Then, the generation that came after that was educated in democratized Taiwan, so I get the impression that views and ways of thinking about Japan differ depending on each generation. Even if we focus on young people today, some like Japan, and some loathe it. I accept both of them. When you think about it, even negative feelings arise from our awareness of the other side. We take time to consider these people. In that sense, there is always a possibility that through friendly exchanges, those feelings will change for the better.

In Taiwan Identity, you interviewed Go Masao, a Taiwanese who lives in Yokohama. He fought in the Japanese army during the Pacific War and was taken prisoner. However, he was unable to obtain Japanese citizenship. Why is that? What is the Japanese government’s policy towards people like Go-san?

First of all, I feel really ashamed as a Japanese. I want to ask the Ministry of Justice why they acted like that. Let me give you a little historical background. Under Japanese rule, about 210,000 Taiwanese were sent to war as soldiers or military personnel. About 30,000 of them died, but for many years nobody seemed to care about them. Then, in 1974, a man from the Ami tribe, an indigenous tribe in Taiwan, was found in Indonesia. He was living in the jungle, believing the war was not over yet. When he was found, talk of compensation for the Taiwanese who fought in the former Japanese army suddenly came up in Japan, but it was not until 1987 that a bill was passed by the Diet to pay condolence money to those who died and those who were seriously injured. Each person was paid two million yen. During the war, they received a salary, but that money was all deposited in postal savings. So, after the war, the question arose of what to do with those deposits. In the end, it was decided to pay 120 times the remaining amount. However, the value of money, such as the price of goods, was completely different, so even that sum was very small. As you can imagine, the former Taiwanese soldiers were extremely angry.

Then there were those who had been interned in Siberia, like Go-san. A law called the Siberia Special Measures Act was enacted in 2010, which provided special benefits to those soldiers ranging between 250,000 and 1.5 million yen per person depending on the time spent in detention. However, it was only available to people who were still alive and had acquired Japanese nationality. So, at that point, Go-san was excluded.

At that time, he told me two things: that he felt like Japan’s bureaucrats didn’t want to waste tax money on Taiwanese soldiers; and that the Japanese government was just waiting for them to die. The Japanese government bears a heavy responsibility in all this mess. It’s truly a sad story. It’s painful, embarrassing, and pathetic. As a Japanese person, I find this really unbearable.

Taiwan is a popular tourist destination for Japanese people, but I think that young tourists in particular don’t know much about the relationship between Japan and Taiwan in the past. What do you want Japanese audiences to take away from watching your films?

First of all, I want people to be aware of the basic fact that Taiwan was once part of Japan. On top of that, I want people to remember that that period is not a distant memory, but we are still connected. As time goes by, the number of people who appeared in the films is gradually dying but some of the people who experienced the colonial period are still alive. So I would be happy if the film could be a catalyst for people to think about the lives of those people and learn more about Taiwan.

In Taiwan Banzai, you went south and interviewed fishermen and people living in the countryside. Do you think that region is very different from the image of Taiwan that Japanese people have?

It may be different for people whose main interests are visiting Taipei 101 and eating xiaolongbao and mango shaved ice. For people of our generation who have seen a lot of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s movies, I don’t think the South is that far removed from what we saw in those stories. After all, many of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s films are set in the countryside. Some people say that those landscapes remind them of the Japanese countryside or the Japan of the past.

I’ve traveled to Taiwan since 1998, and up until the early 2000s, Japanese people had not been very interested in that country. In a sense, the tide turned after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, when the Taiwanese sent a lot of relief money to Japan. My impression is that since then, more people here have started to look at Taiwan properly.

This said, even now, whenever Taiwan is featured on TV, it tends to be about food and other superficial information. That may be why I have kept making films on this subject. I want everyone to know that Taiwan is not just about food. It’s about their people. I want the Japanese to come to Taiwan and meet their people.

Your project has been going on for many years now. What did I learn about Taiwan, and what impressed you the most?

For me, learning about Taiwan was the same as learning about Japan. What did Japan do in Taiwan when it ruled the country for 50 years before and during the war, and what did Japan fail to do after the war? Visiting Taiwan has given me the chance to see myself clearly, like a mirror.

Another important thing is that for a long time after the war, Taiwan was under martial law during the dictatorship, but with the emergence of Lee Teng-hui, democratization began, and now it is a truly democratic society. A presidential election was held this January, and the voter turnout was 71.86%. In comparison, the recent Tokyo gubernatorial election made the headlines because it was the first to reach 60% in 12 years The most recent House of Representatives election was in 2021 and had a 55.93% turnout. What I want to say is that the young people in Taiwan today understand very well that this democratic society was won by the adults with their blood, sweat and tears. That is why they value their right to vote so much, and they are ready to show that they will never tolerate any actions by those in power. On the other hand, my country, Japan, is in the opposite situation. Another thing is that in 2019 Taiwan became the first Asian country to recognize same-sex marriage. I feel that we Japanese have a lot to learn from Taiwan today.

I heard that you are not done yet with your film-making.

Yes, I’m working on a fourth documentary. This time I’m focusing on Orchid Island, a small island off the southeast coast of Taiwan inhabited by the Tao people, an indigenous people with a strong maritime culture. The project was interrupted by the pandemic and we haven’t fully resumed yet. Also, we have to be careful about how we approach the Tao’s unique human relationships. Therefore, I’ll keep raising funds and building a closer relationship with the locals before starting filming.

Interview by Gianni Simone

To learn more on this topic, check out our other articles :

N°143 [TRAVEL] The ideal tourist is Taiwanese

N°143 [FOCUS] History : Could Do So Much Better

N°143 [Eating & Drinking] Conquering Japanese Tastes

Follow us !