Fishing is a pastime enjoyed by millions of people in the Archipelago. And has been for a very long time.

Japan is attracting millions of people from around the world thanks to its unique culture, delicious cuisine and spectacular nature. However, not many people know that Japan is also a fishing paradise. First of all, Japan’s diverse ecosystem provides an ideal environment for fishing. From freshwater mountain streams to oceanic waters, you’ll find an impressive variety of fish species. Locations, of course, play a central part in how much you are going to enjoy your outing, and Japan offers breathtaking locations for any kind of fishing. This is also because most Japanese anglers prioritize nature conservation. Their commitment to sustainable fishing ensures that future generations can continue to enjoy this angler’s paradise.

In other words, whether you are an experienced angler or a beginner, Japan promises unforgettable fishing adventures.

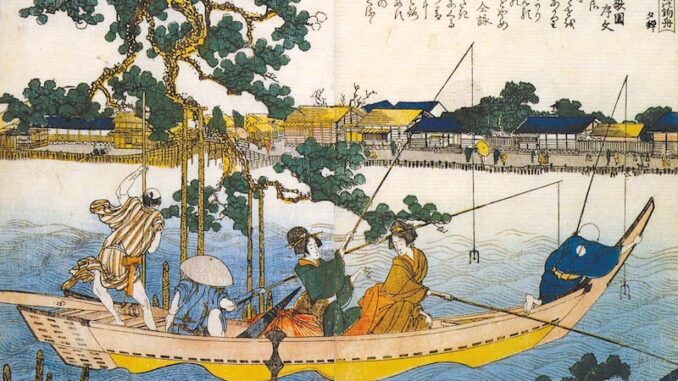

Fishing in Japan has a long history. The first records of such an activity date back to the Kofun period (250-538 AD) when, according to the Nihon Shoki (8th century), one of the oldest books on Japanese history, it was also used as a ritual to predict the outcome of a war. Again, in the 8th century, fishing appears in Japanese literature. In fact, it’s mentioned in both the Kojiki (a chronicle of myths, legends, hymns, genealogies, oral traditions and semi-historical accounts) and Man’yoshu (the oldest collection of classical Japanese poetry). According to one story, for instance, the legendary Empress Jingu used to go fishing for ayu sweetfish by using grains of rice as bait.

There are also records of Emperor Junna and Emperor Ninmyo fishing for fun in the early Heian period (794-1185), though there are few records of fishing throughout the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (between 1185 and 1568). It was only in the Edo period (1603-1867) that recreational fishing became popular throughout the country and was embraced as a hobby by both the samurai and the common people.

Several reasons led to this phenomenon, all linked to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. According to Nagatsuji Shohei, author of Fishing in Edo: A Hobby Culture That Flourished on the Waterfront, since there were no major wars for more than 200 years during the Edo period, more people could at last relax and embrace a hobby. The samurai, in particular, found themselves with a lot of free time. Both the shogunate and each domain continued to maintain large armies, many of which were stationed in Edo. However, not having to go into battle, some of them were employed as bureaucrats, while about 40% of the former warrior class were organized into small construction groups whose only work was repairing castles. It’s no wonder that fishing became popular among them.

Samurai in Edo not only had the time to fish but also lived in the perfect environment to enjoy their pastime as the shogunal capital had an extensive network of canals and water transport, and there were fishing spots everywhere. Edo Bay was home to many fish and shellfish species. It had many large and small sandbanks and gravel bars created by sand and soil carried down by the large rivers that flowed into it, while the coastal area was lined with ditches for water management and a network of artificial waterways, which became a perfect environment for fishing.

Another factor related to the establishment of the city of Edo as the de-facto capital of Japan was the growing number of shipwrecks in Edo Bay. For the construction of Edo Castle, ships were constantly carrying stones from the Shizuoka area to Edo. Many of them sank in the bay creating ideal artificial reefs. Reef fish such as sea bream and greenling gathered there, making it a perfect fishing spot.

The only thing lacking was moral approval of fishing. Until the end of the 16th century, Buddhist temples had enjoyed both political power and religious influence over the population for centuries, and Japanese customs and eating habits had been influenced by Buddhism’s precept against killing and eating animals. However, the temples lost much of their power under the Tokugawa. This freed people to go fishing.

This trend was temporarily halted by the fifth shogun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1680-1709). A fervent believer and dog lover, from the early 1690s Tsunayoshi began to release a series of Edicts on Compassion for Living Things that brought about a revival of the Buddhist ban on killing animals. However, the edicts were abolished on the same day Tsunayoshi died. The 15-year dark period for fishing was finally over, and fishing began to thrive once again.

During the 18th century, the Edo-period fishing boom led to the publication of several books and manuals on the subject. Tsugaru Unemenosho, for instance, was a samurai who married the daughter of Kira Yoshinaka, the “bad guy” who was killed by the 47 loyal ronin (independent samurai) portrayed in the play Chushingura. He was said to be a fishing fanatic, and in 1723 wrote an introductory guide to fishing called Kasenroku. The first volume covers fishing spots off the coast of Shinagawa in Tokyo, and the second volume includes information on fishing gear and bait. Other books came out in 1770 and 1788 listing, among other things, the names of local fishing gear dealers.

Fishing equipment during the Edo period was of the highest standard thanks to the application of military skills to civilian life. For example, bow and arrow processing techniques, previously used to straighten bamboo materials and make them into poles, were used to make fishing rods. Also, lacquer, which had been long used for hardening the sheaths of Japanese swords, was applied to fishing rods to make them both durable and beautiful. Even lead gun shot was used to make fishing weights.

In Europe, they didn’t have bamboo, so they used wooden fishing rods, but they lacked the sensitivity of Japanese bamboo rods. That’s how, starting from the Meiji period (1868-1911), made-in-Japan gear earned foreign currency as an export product.

During the 20th century, recreational fishing became increasingly popular. In 1973, the Japan Fishing Promotion Association was established and, for the first time, surveys were done on the actual number, structure and orientation of the fishing population. According to the first census, the fishing population was estimated to be 14.5 million and in 1978, rose to 17.61 million anglers and 42,000 recreational fishing guide boats.

As often happens in Japan, pop culture contributed to the dramatic increase in the fishing population. From the 1970s to the 1990s, in particular, the success of such manga as Tsurikichi Sanpei (1973-83) and Tsuri baka nisshi (Fishing Nut’s Diary, 1979-present) greatly contributed to popularizing the hobby.

This huge increase (also fuelled by the boom in black bass fishing), together with water pollution and land reclamation associated with urban development, caused the fish population to decline both inland and at sea. As a consequence, to protect freshwater fish, each prefecture enacted stricter recreational fishing regulations including establishing fishing seasons, prohibition of certain fishing methods and other measures to protect different fish species. Anglers were also required to pay fishing fees set by the association. Those fees were used for breeding and protecting fish.

There are no such regulations regarding saltwater fish. However, the government has mandated a temporary fishing ban around areas where young fish are released. The National Fisheries Research and Education Agency and prefectural fishery centres are taking the lead in efforts to protect breeding fish.

Until the early 1990s, the number of people fishing as a hobby continued to increase to the point that it was said to be around 20 million people. However, following the burst of the Bubble economy and the recession, coupled with the decline of the bass fishing boom, new port regulations and other factors, the number of anglers began to rapidly fall. According to the Japan Productivity Centre’s Leisure White Paper, the number of recreational fishermen declined to 12.9 million in 2006, 7.1 million in 2013 and 6.2 million in 2018.

Ironically enough, the hobby was recently rescued by the Covid-19 pandemic. Amid social distancing measures in which people were asked to refrain from travelling domestically and eating out, fishing became popular again as an outdoor leisure activity that could be easily enjoyed with a low risk of infection. As a consequence, river embankments, piers and other facilities where you can fish along the coast were again filled with anglers on weekends.

The new fishing boom has attracted women and children as well. Until a few years ago, fishing was associated with getting one’s hands dirty and smelly from handling earthworms, lugworms and other live bait. However, with the evolution of fishing equipment and the diversification of fishing methods, more women now enjoy “smart” fishing by using artificial lures.

Indeed, lure fishing has been the biggest success in recent years. Although the popularity of black bass has waned, lure fishing has expanded to all areas, regardless of whether it’s saltwater, freshwater or brackish water (places where freshwater and seawater mix at the mouth of an estuary). Lures are made in countless ways, including colourful metal jigs and rubber worms, and are used to catch all kinds of fish including sea bass, yellowtail, red sea bream, flounder, cutlassfish and horse mackerel.

In general, fishing gear has become smaller and lighter. Catching big fish with thick nylon lines used to require a large reel, heavy weights and a long, heavy rod that could withstand them, but now it’s possible to catch them with light tackle, making the pastime even more interesting.

The fishing-related business also seems to be doing well. According to a survey by the Japan Fishing Products Industry Association, domestic shipments of fishing supplies in 2020 grew by just under 7% to 149.13 billion yen with a 106.7% increase from the previous year, and to 156.82 billion yen in 2021. Additionally, in January of the same year, the online edition of the Nikkei Shimbun daily published an article stating that Globeride, a major fishing gear company that manufactures the world-famous Daiwa brand, would build a new factory in Vietnam with an investment of 2 billion yen. The new factory is expected to increase overall production capacity by 10%.

While for many years Japanese companies ruled the global market with their cars and appliances, few people know that Japan holds the world’s No. 1 sales position in the fishing gear industry, and Globeride is the world’s largest comprehensive fishing equipment company. The Tokyo-based company’s name may not be as famous as Toyota and Sony but its fishing gear sales are 100 billion yen worldwide. While most of its sales are in Japan (65%), it has also established a strong presence in Asia/Oceania (16.4%), Europe (10.5%) and North America (8.0%).

Gianni Simone

To learn more on this topic, check out our other articles :

N°142 [PRESS] Tsuribito is still going strong

N°142 [SEA] An all-consuming passion

N°142 [TOKYO] With the city-centre anglers

Follow us !