Two curators, specialists in manga, share their vision of the work that remains to be done.

Omote Tomoyuki is currently a specialist researcher at the Kitakyushu City Manga Museum (KKMM). His major is in history of thought and manga research. Ito Yuu is a researcher at the Kyoto International Manga Museum (KIMM)/Kyoto Seika University International Manga Research Centre. He is also in charge of curating numerous manga exhibitions.

There is growing interest in establishing manga museums in various prefectures and cities as they recognize the importance of pop culture and aim to attract more tourists. What do you think about this phenomenon?

Omote: Up until a certain point, when local government organizations supported and promoted culture, they focused on high culture. However, the younger generations tend to be more attracted to pop culture, so as a natural progression, both local authorities and cultural operators are now devoting more space to pop culture events and exhibitions. In the case of manga museums, attracting tourists is of course an important goal, but they’re also the product of a growing consensus that manga and anime should be treated with the same respect usually accorded to art and theatre.

Many famous manga artists have strong connections with the place where they grew up. Think about Mizuki Shigeru and Tottori Prefecture. These artists often have a huge number of manga manuscripts, but it’s often difficult for the individual author (or their family after the author’s death) to manage them. However, since each piece is hand-drawn and offers a unique window into the artist’s work, we can’t just discard them. In recent years, both manga artists and publishers have been calling for the preservation of those works before they’re lost, so this is also something that we must keep in mind when we consider the recent growth of manga museums.

Ito: Around the beginning of 2000, the government announced that the country would use manga and anime to enhance Japan’s profile abroad. In response to this, local government, prefectures and cities began to use pop culture as a new tourism resource to act as a catalyst to attract people. They started holding events and exhibitions and thought it would be great to have a facility like a manga museum.

These places have opened everywhere. I counted about 70 manga-related facilities throughout Japan. However, most of them are devoted to popular manga characters or a single artist. Moreover, a lot of those facilities are based on the idea that a popular character or artist will attract a comparable number of visitors as their fans. I think that’s quite a misconception. For example, each volume of One Piece sells about 4.9 million copies worldwide, so one might think that a hypothetical One Piece Museum would be visited by more than 4 million people. Obviously, that’s not the case.

Also, ideally, a manga museum should do all sorts of things such as holding events, creating exhibitions and conducting research. However, out of the 70 or so manga facilities I found, most of them have few if any experts among their staff. I personally know of only five or so. Granted, one could say, okay, we have limited staff, but the character or artist our museum is devoted to is popular enough that people will come anyway. Which is true, to a certain extent. At the same time, I believe that we should ask ourselves what is attractive about them. If we don’t have people who are constantly researching things and can explain them to the public, we’ll end up with an unsustainable situation. In other words, they may attract a lot of people at first, but in time the number of visitors will likely decrease. I don’t mean to say that such museums shouldn’t be built. It’s just that they should expand the scope of their activity.

I’m sure you’ve visited many museums in various places. Which one is your favourite?

Omote: In the sense that it’s completely different from what we do in Kitakyushu and other big cities, the places that stand out for me are those that were set up in small towns. In those cases, I get a very strong impression that the whole community is involved because they consider a certain artist a sort of local treasure. In this respect, I’m very interested in the Yokote Manga Art Museum in Yokote City, Akita Prefecture. When it comes to preserving manga manuscripts and original art, this place has 400,000 items in its collection and has all sorts of on-going initiatives and collaborations.

Another place I love is the well-known Mizuki Shigeru Memorial Museum in Sakaiminato. When you visit that city, you discover many bronze statues of yokai characters all over the town, and the fact that the whole place has become associated with Mizuki has left a lasting impression on me. I confess, I’m a little jealous of what they’ve accomplished.

Among the activities of a manga museum are research, the preservation of artworks and materials, and exhibitions. What is the relationship between those three things?

Omote: It all starts with research. Primarily, at KKMM, we carefully preserve and look for original art and publications by local people. In the case of manga, this is the most difficult but also the most important part because there are many things you can’t understand about those works unless you have a proper bibliography. If the person is famous enough, there are many articles and publications available. For authors like Matsumoto Leiji (KKMM’s former Honorary Director), for example, we already have such materials. But with less famous people we’re not so lucky, so we search for materials, collect and record them. Having done that, we try to understand the nature of that artist’s work. More specifically, we try to dig deeper into what kind of relationship they have with Kitakyushu and how the city has influenced their art and stories. Currently, we have more than 200,000 manga manuscripts to evaluate, and we can’t seem to keep up with them, so we have a hard time sorting them out in detail. Eventually, we gather some of the materials we have and display them.

Then there’s a completely different kind of manga exhibition: travelling shows usually organized by newspaper companies. They do all the hard work: come up with a theme, obtain permission from the artist or publisher, borrow materials and sell the exhibitions to museums across the country. Then it’s their job to transport the exhibits, install them, take them down and return the works to the owners besides taking care of the financial side of the event.

At KKMM, our budget is limited, so we can afford to hold only one exhibition per year. However, in addition to the events connected to our research, we’ve recently been increasing the number of collaborations with other manga museums. Sometimes we begin by forming a team and create things together, sometimes we borrow exhibitions from other institutions, and sometimes we rent out things we’ve created ourselves. When we put on something created by another facility, we receive a complete list of works and explanations from them, and based on that list, we go back to the artist to borrow the original artwork and put it on display. Therefore, we do the same physical work but we can skip the planning stage, so the overall work load is much lighter. We’ve seen an increase in the number of joint projects. I think it’s important we keep cooperating so that we can use each other’s work and expertise.

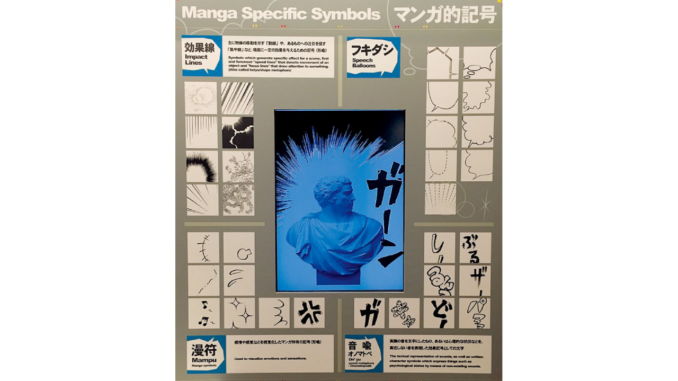

Ito: Very few manga museums currently operate as academic facilities for the purpose of manga research. Another one is the Yonezawa Yoshihiro Memorial Library/Contemporary Manga Library which is run by Meiji University in Tokyo. Here, of course, we put on things like exhibitions, events and workshops, but everything starts with research. Through our collection and study activities we come up with ideas to present the results of our research to the general public. We’re always experimenting with new ways to show visitors how amazing manga are. Most people’s interaction with comics comes from reading books and magazines, but at our museum they discover a different way to approach them, which we hope is both fun and informative. Take character-related merchandise. As you know, they sell a lot of manga-related stationery and apparel. A doll or a piece of stationery is not a manga work, but fans buy and collect them specifically because they like them, and it’s a different way to relate to the stories they love. Also, manga fans usually read so fast that they often miss many visual details, but when they look at an original picture at a manga exhibition they have an opportunity to slow down and see all those details. This enhances their understanding of manga as a medium and how storytelling works in comics. Another thing we do is invite a manga artist who can explain what he does and all the behind-the-scenes work that goes into creating a story. Again, this is a different way of enjoying a manga. Reading is a solitary experience, but at a museum event people are united in sharing their love for manga.

For example, we have a regular event at KIMM where every year we invite Ueyama Tochi, who makes a cookery manga called Cooking Papa that’s been published since 1985. Each time, Ueyama prepares some of the dishes that appear in his stories in front of the visitors. This way, fans can actually taste and smell the food and see how it is cooked. It’s something that is both complementary to and goes beyond the act of reading manga.

What is an ideal manga exhibition for you?

Omote: There are two ways to do it. One is focusing on the charm of the original art itself. If you already know the artist or his work, you have a chance to admire their original drawings and marvel at their beauty. On the other hand, it can be difficult to understand what is actually amazing about them or how technically wonderful they are. So, the organizer’s job is to make sure that we explain properly what the visitors are seeing. As you can imagine, this kind of exhibition is an event that appeals to fans of a particular artist or manga as they have the opportunity to discover something they didn’t know about them and to dig deeper into their world.

On the other hand, there are exhibitions where the public doesn’t know anything about the subject or theme. In this case, we aim to showcase an artist’s method, style and approach to storytelling; how amazing a manga manuscript is or how unique their drawing and writing style is. In other cases, we may highlight the fact that a manuscript is the product of a six-member staff team, and explain what each person contributed to the story. It can take the form of an analysis of their technique or an explanation of their method of working; anything that helps us understand better the process of manga-making.

One problem we invariably have to solve whenever we put on an exhibition is how best to explain all those things. We don’t have much space available, so we have to figure out how to convey that kind of information in a few short sentences.

For me, the ideal exhibition presents the social issues and cultural aspects of the time when an artist was active or a certain work was published. Or it explains what works preceded and maybe influenced a particular manga or were featured in the same magazine of that era. Anything comes in handy in portraying a bigger picture of the times and cultural climate in which a manga was created. Illustrating the breadth and depth of a work-of-art’s background helps fans understand why a particular work is so wonderful.

Ito: When you read a manga in book-form or on a tablet or smartphone, you only need a small space to enjoy it. A museum, on the other hand, gives you an opportunity to enjoy whatever the subject is in a big space, so we need to find ways to use that space to our advantage to offer the public a unique experience. For example, the images that look so small in a book can be blown up and printed out much bigger. It’s always fun when people look at something they know well from a different perspective. Also, as I said, we do research-based exhibitions. That way, a museum becomes a place where we introduce comics that people have never seen, like French or African comics.

In Japan, the number of comic exhibitions has increased considerably recently and, according to my estimates, there are about 170 or 180 exhibitions every year. In about 60% of cases, they are comprised of framed original drawings and manuscripts. My impression is that most of those exhibitions are put on by the publishers as a sort of service for fans. Consequently, they’re mainly about popular works and famous cartoonists, and they’re overwhelmingly attended by their fans.

It’s not that those exhibitions aren’t interesting, mind you. It’s just that they turn into a sort of ritual or an event in which fans reaffirm their love for the works exhibited. In this sense, they don’t really “see” what is shown. They also miss out on experiencing events about manga artists and works they don’t know.

These days, the internet is full of digital manga, and I heard that this medium is also used in manga exhibitions. What do you think about this phenomenon?

Ito: KIMM specializes in collecting quite old manga-related materials and documents. Specifically, we have a lot of ukiyo-e from the Edo period (1603-1867) and materials from the Meiji era (1868-1911) and the Taisho era (1912-25). We also have postwar materials, but other facilities have similar collections from the late 1940s onward, so we focus on older items.

As you said, many recent manga works are only made digitally and are not printed on paper. Indeed, so-called webtoons (digital comics published on one long, vertical strip, which is easier to read on a smartphone or computer) are very popular now. I confess I haven’t done much research in this field, but an increasing number of experts are devoting their time to studying them, so I expect that more exhibitions will be devoted to the digital medium in the future.

Omote: At Kitakyushu, we’re still developing this side of manga production. As I said earlier, our exhibitions tend to focus on the behind-the-scenes aspects of manga-making and, in that sense, original manuscripts are the easiest to use as exhibits. In any case, I don’t think there’s a well-established methodology related to digital manga right now. The fact is that when it comes to digital production, some things are a little difficult to imagine when what you have in front of you is just a printout of image data or a monitor. I think it would be fun to approach such exhibitions by using a time-lapse method where someone takes pictures of the digital writing process at different times. But of course, it’s not a method that can be used all the time as it’s limited to cases when the artist has left such records.

This said, there’s a lot of potential in the digital medium, and South Korea has done a lot of things we can learn from. On the internet, vertically scrolling comics are popular in South Korea, and they’ve even opened a museum devoted to this genre, the Busan Webtoon Centre. I cooperate with the Webtoon Festival every year, and I’ve seen how creatively they set up their exhibitions, for example, by printing out images of the works and pasting them all over the walls, ceiling and other places in the exhibition hall. Their use of enlarged images makes it seem like you’re inside the work, allowing you to experience the artist’s worldview with very interesting results. In other words, what makes those exhibitions so engaging is the way they approach space design.

Another thing that is currently being tested in Busan is pairing images and music. They ask an artist to draw an illustration of some beautiful scenery of Busan at night, and then ask a musician to compose a new song inspired by that image.

In Japan, I’m afraid there’s still a lot of work to do in this area. Unless we improve our skills, I think it’ll be difficult to create attractive digital exhibitions.

Among the exhibitions organized by the museum so far, is there one you are particularly proud of?

Omote: The exhibition that impressed me the most was the one devoted to Morohoshi Daijiro, in 2021. This was a rather unusual type of exhibition, in which the manga artist displayed the myths, legends and historical materials that he incorporates into his work. Morohoshi has published such manga as Yokai Hunter, Ankoku Shinwa (Dark Myth) and Koshi Ankokuden (Dark Biography of Confucius) and is famous for basing his stories on ancient history, mythology and folklore, even pseudohistory. In that particular exhibition, historical materials and original artworks were combined to create a whole semi-fictional world where you didn’t know where reality ended and where fiction started. The result was very interesting and received a lot of feedback.

Of course, I personally love the artist himself, but I also think that he showed new possibilities in that manga exhibition. In showing how his works originate, he didn’t create your typical historical background but a dense, complex network of history, myths, legends and fairy tales. In order to understand what kind of reference was used to convey a certain story, it’s necessary to provide real materials like those related to the history and myths that were referenced in Morohoshi’s works. For example, he writes a lot of comics that deal with archeology, so we borrowed the real pottery and excavated materials that appear in his work. He also made a manga based on Journey to the West, a Chinese novel published in the 16th century, so we displayed an old hanging scroll related to that kind of Chinese mythology.

In addition to displaying such historical materials and the original manuscripts, there was a corner in the museum where visitors were free to read Morohoshi’s books, so they could compare the finished works with the creative process the author went through. It’s always interesting to see how someone comes up with such an unconventional story based on that historical background.

How do you see the future of manga museums?

Omote: As for issues within manga projects, our museum is involved in studying ways to create the conditions for local authors to improve their earning capacity, for example, by attracting publishing companies. Also, over the past ten years, we’ve collected a lot of material, so I’d like to strengthen the dissemination of information. Specifically, I’d like to publish a list of the material in our possession in the form of a database. There’s already a system in place that allows users to search for such material online, but organizing and presenting all this information takes time. In addition to manga books, we’ve been collecting many newspaper and magazine articles, so our database also becomes a site for those who want to do serious research.

To sum up, as a cultural facility for the general public, we’ve reached a certain level of recognition and achievement, but I’d like to strengthen communication and collaboration at the research level. This way, I believe that we can create a system that will deepen our interaction with other museums and create opportunities for more exhibitions. That’s our next challenge.

Omote: Over the past ten years or so, people involved in manga museums, including myself, have been building networks to connect all these facilities. We aim to overcome a museum’s physical limitations. KIMM, for example, has some 300,000 books. It may look like a huge number, but when you consider that nowadays more than 10,000 titles are published every year in Japan, you realize that even 300,000 volumes are just a drop in the ocean. Obviously, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to collect all the manga in one place, so we’d like to create something like a nationwide museum system through a network comprised of various facilities, individual collectors and other people who are interested in manga. Such a network will allow each member to share information and to lend and borrow materials easily through an online database. That’s our main goal, and I’m currently working on increasing my contacts for this purpose. We’re working with art museums as we think it would be great if we could collaborate with them and create something like a Japanese Manga Museum.

Interview by Gianni Simone

To learn more on the subject, check out our other articles :

N°137 [FOCUS] Welcome to manga in the museum

N°137 [KITAKYUSHU] Showcasing local creativity

N°137 [KYOTO] KIMM: a textbook case

Follow us !