The best-known museum devoted to manga has set the standard since it first opened its doors in 2006.

One of the biggest and most important manga museums in Japan can be found in Kyoto. Opened in 2006, the Kyoto International Manga Museum (KIMM) is housed in a former elementary school, which was originally built in 1929, and it has a distinctive retro feeling. It’s very popular with foreigners too, and currently 15% of its visitors come from abroad. This is one of the most ambitious manga-related projects in Japan as it aims to introduce the public to the world of comics from a historical, artistic and sociological point of view.

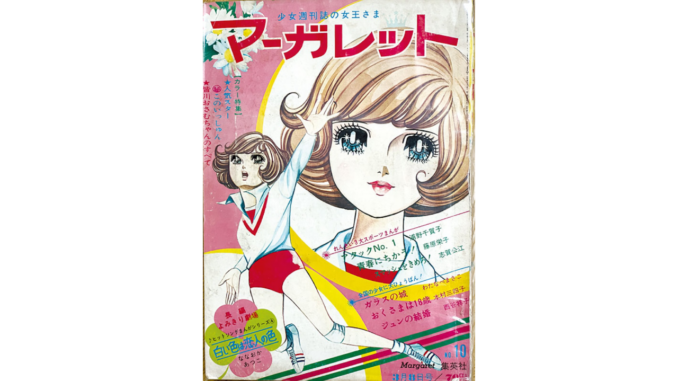

The temporary exhibitions focus on particular periods (e.g. manga during the war), authors, magazines (e.g. Margaret) or regions (manga in Okinawa), and even covers the foreign manga scene (e.g. African comics). The permanent collection includes nearly 200 maiko (apprentice geisha) portraits made by manga artists, and another fascinating (or slightly disturbing, depending on your tastes) display of plaster casts of over 100 artists’ hands.

The museum library has a collection of 300,000 volumes, 50,000 of which are available on open-stack shelves – the so-called Wall of Manga. The first floor is devoted to shonen (boys) manga, the second to shojo (girls) manga, and the third to seinen (young adults) manga. A few specialized areas include the Manga Hall of Fame (arranged by year from 1945 to 2005), the MM navigation shelf focusing on a particular theme, and Manga Expo where you can read manga in other languages (about 1,000 are in English and 1,600 in Chinese).

250,000 older and rarer items can be accessed in the Research Reference Room on registering (all details online). All this material is mainly intended for research purposes.

In the Manga Kobo (Manga Studio) corner, you can watch an actual manga artist working, while in the Portrait Corner you can have a professional illustrator draw your face in standard or anime style. It takes about 30 minutes. If you plan to do that, be sure to come early as it’s very popular with visitors.

Among other activities, two or three times a day you can watch kami shibai (literally, paper play), a traditional form of street theatre and storytelling, which was very popular with kids until the mid-50s. They even have workshops where you can learn how to draw manga etc. Some of them require a reservation and an additional fee.

Speaking about the museum’s origin, KIMM curator Ito Yuu talks about how attitudes toward manga and otaku culture in general changed at the turn of the century. “Roughly speaking, manga was a subculture until around 2000,” he says, “but since the 2000s it has increasingly been accepted as an essential part of Japanese culture and society. There are several reasons for this, but one of them is that Japanese comics became very popular in France and other foreign countries, and that recognition has helped change popular opinions in Japan as well. In the past, many people thought that manga were only for children, but now they are realizing that they’re bigger and more diverse than that and have a more pervasive presence in Japanese culture.

“Also, from the 2000s onwards, manga and anime became important research fields. In 2001, for example, an academic group called the Japan Society for Studies in Cartoons and Comics was formed at Kyoto Seika University. The next step was to create a place that would collect materials that could be available to researchers, and Seika University came up with the idea of opening a place that could be both a manga museum and a research institute. So, we asked City Hall and found that there was a school in Kyoto that was no longer in use.

“Eventually, we expanded on the original idea and were able to create a facility for manga research that would also function as a library and museum with presentations that could be enjoyed by the general public. We then hit on the idea of holding workshops, so when KIMM finally opened in 2006, it had become an institution with many complex functions. I’m glad to say that our museum has quickly become the go-to place for both serious manga fans and professionals, from authors to publishers and researchers, and we also have a sizeable number of visitors from overseas.”

One of the more appealing points of KIMM is its location. The main building was built in 1929, the auditorium and gymnasium in 1928 and the north wing in 1937, which means the whole complex is almost 100 years old, a real rarity in Japan. Reading chairs are available everywhere including hallways, stairs, rooms and in front of lifts. If the weather is nice, we recommend bringing your manga into the courtyard. It’s covered with artificial grass, and you’re welcome to sit or lie down and relax while enjoying your favourite titles.

Speaking of manga books, there are so many works on display on open-stack shelves that people visiting for the first time will definitely need to use the search device. There’as one on each floor, and just by entering the manga title, the machine shows you the shelf where the manga is located. Only one copy of each manga is available, so if you’re looking for a popular title you should arrive early. By the way, there’s a limit of five copies of popular manga (e.g. One Piece, Demon Slayer, Spy x Family, Jujutsu Kaisen) you can request each time, but for less popular titles, you can take as many books as you like.

The museum also has a souvenir shop that sells manga T-shirts, postcards, magnets and wallets as well as English translations of comics that are popular overseas. If you want a memento of your visit, there are also commemorative medals with designs from such works by Tezuka Osamu as Phoenix, Black Jack, Astro Boy and Jungle Emperor. You can enter your name and the date of your visit.

“Many manga museums in Japan tend to focus on a single character or author,” Ito says. “Obviously, by their very nature, they only attract fans of those works and artists. However, we want to cover the whole gamut of manga production and showcase comics as important artefacts. Rather than just displaying well-known works, we prefer to introduce worthwhile but unknown works. For example, Japanese manga fans do not know much about overseas comics, so we have many foreign comic exhibitions about countries such as France or Africa. I think there are only a few people in Japan who know about African comics, and we want to show that there are a whole lot of engaging, thought-provoking and beautiful manga outside Japan, which are very different from what people in this country are used to. This, in the end, is our true mission.

Gianni Simone

To learn more on the subject, check out our other articles :

N°137 [ENCOUNTER] A heritage to protect

N°137 [FOCUS] Welcome to manga in the museum

N°137 [KITAKYUSHU] Showcasing local creativity

Follow us !