In Fifty Sounds (2021), a memoir about her time spent in Japan, translator and author Polly Barton remembers the day a Japanese friend took her and her brother to a yakiniku (grilled meat) restaurant. “Upon learning that my brother didn’t eat meat, [my friend] said blithely, ‘Don’t worry, they have sausage.’.” This surreal scene says a lot about the current state of veganism in Japan, particularly outside of the big cities (Barton was living in Niigata Prefecture at the time).

We talked about vegetarianism’s current outlook with Kato Hiroko, a freelance writer who for more than 20 years has covered Japanese food culture.

I guess you are a vegetarian or vegan?

Yes, I am. To be precise, I don’t eat meat.

How and why did you stop eating meat?

In 1999, when I became a freelancer, I wanted to work in America, and the company that accepted me into their programme was a nonprofit organization called Vegetarian Resource Group. I’d never been a vegetarian or vegan before, but since I was working for them, I thought I’d give veganism a try. I stayed there for about six months and during that time, I started to think that going vegan was a really good option for me. That’s how I got started.

How about your family?

No, it’s just me (laughs). When I cook a meat dish for them, I prepare something different for myself. It’s a difficult lifestyle, especially if you live with your family or other people. A good compromise for those who are thinking about adopting a vegetarian diet would be to start with Meatless Monday, a practice made popular by Paul McCartney. In other words, you become a vegetarian for just one day of the week.

Sometimes, the difference between vegetarian and vegan differs depending on the country. How about Japan?

I think Japan has a fish problem. There are many definitions of vegetarianism. For example, the International Vegetarian Union defines a vegetarian as someone who does not eat meat or fish. Among vegetarians, some eat eggs and/or dairy products, but in Japan there are also people who eat fish – so-called pescatarians. Even more strangely, some people eat chicken, though I don’t think they can be called vegetarians. That’s the major difference between Japan and Western countries.

In Japan, katsuo dashi (bonito stock) made from dried and shaved bonito tuna is often used to heighten flavours and add a distinct umami taste to soups. It’s an essential part of traditional cooking and it’s very difficult to avoid.

Another thing setting Japan apart from other countries is that vegan food is becoming more fashionable and trendy right now, but rather than becoming a vegetarian because of ideological reasons, many people here embrace vegetarianism because they want to lose weight or it’s good for their diet. I think there are probably a lot of people, especially among the young, who are interested in veganism because it’s such a trendy thing to do. I’m afraid many of them don’t understand that veganism is not just a diet, but a lifestyle that stems from the idea that animals should not be exploited for human consumption.

Sweets are another example. Now some manufacturers are using the catchphrase “guilt-free and vegan” as an advertising slogan, but I think that when they say vegan, they probably mean plant-based.

It must be difficult to live a vegan or vegetarian life in Japan.

Yes, very much so. In Japan, you must have a strong motivation to change your lifestyle to vegan or vegetarian and be aware that you are going to cause confusion among the people around you. When I went to America more than 20 years ago, not only were there regular vegetarian and vegan restaurants but even most of the traditional restaurants had vegetarian and vegan options. There were always one or two items on the menu other than salads. In Japan, we’ve not reached that situation yet, so for example, if you go to a ramen restaurant with your friends, there may not be anything vegetarian available. Tokyo, of course, is better than other places, but especially in small towns and rural areas where you may find nothing.

What is Osaka like?

I went to Osaka around the time the coronavirus pandemic started, so the experience was a while ago, but it wasn’t as good as Tokyo. For example, inside Tokyo Station there are two restaurants that serve vegan ramen and there’s also a shop inside selling vegan bento boxes. If you search around Tokyo Station, or even in other parts of the city, you can find a few more vegetarian and vegan options, but in Osaka there are still very few. At Osaka Station now you’ll find Soup Stock or some other chain serving dishes that don’t contain animal products. I don’t know what will happen with the 2025 World Expo, but there’s a possibility that the large number of people coming from overseas will serve as an incentive for increasing the number of vegetarian restarants in the city. The Tokyo Olympics, for example, were a big factor in pushing up the number of vegan restaurants. Personally, I wasn’t in favour of the Olympics, but in terms of popularizing vegetarianism and veganism, I think the Olympics definitely played a big part. If it weren’t for the Games, I don’t think things would have moved as quickly. Among other things, they led to the creation of a Diet members’ study group which came up with the idea of creating a Vegetarian/Vegan JAS label. (Japanese Agricultural Standards is a national standard established by the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and is proof of high quality and reliability).

The media play an important role in spreading new trends. What is their relationship with vegetarianism? If you look at Japanese TV programmes, there are a lot of shows devoted to food and cooking, but there are almost no programmes about vegetarian and vegan cooking.

Speaking of that, the other day I had an opportunity to take part in a TV programme on food substitutes (fake meat, fake seafood and fake eggs). At that time, the production company was very concerned about the butchers, milk farmers, livestock farmers and other people who are involved in the industry. Because of this, I was asked not to say anything that would sound like criticism. From their pint of view, they probably wanted to avoid any complaints. But I also got the feeling that the media still lacks awareness of the problems meat eating is causing such as the climate crisis and animal rights issues. In the United States, for example, when I read articles in the New York Times, I often find that the reporters who cover those subjects are themselves vegetarians or vegans. However, in Japan, as far as I know, no reporters or newscasters are vegan. For that reason, the media are still testing things: when they cover fake meat, their general stance is something like let’s try it out and see what it’s like.

Do you eat fake meat?

Sometimes. Now there are a lot of fake meat products in supermarkets, but they are still a little hit-and-miss. Some of them are very good.

What are the biggest obstacles to further popularizing vegetarianism in Japan?

I think the biggest obstacle is prejudice. Too many people still believe that only eating meat will make you feel well, or that children need milk. When people in Japan think about gourmet food, they unfailingly think about meat or fish. Vegetables are only seen as side dishes, which is ironic when you consider our long tradition of vegan shojin ryori (Buddhist cuisine). If you take a look at our rich food culture, we have excellent rice, vegetables and various kinds of mushrooms, and you realize that there are many delicacies to be found too. However, when we talk about veganism, we’re still only talking about fake meat stews. We still haven’t recognized the fact that vegetables on their own are delicious and nutritious, that vegetables alone are enough for a good and well-balanced diet.

This kind of dietary conformism starts from an early age. In elementary schools, for example, every child is expected to eat the same thing. They may make an exception if you have allergies or some life-threatening medical condition and eating a particular food would put you in danger, but if you say your child is vegetarian they will ask you to bring your own lunch. For them, that’s just a matter of likes and dislikes. In other words, you’re just being selfish.

That’s why I’m saying that unless there’s a change in mindset about what is good to eat, I think vegetarians and vegans will continue to be in the minority. I also think that for the Japanese to drastically change their ideas, something big must come from the outside. The Olympics, as I said, were very influential. Then there’s inbound tourism. I think that by interacting with people from other countries, more Japanese will realize that food is of such great importance that it transcends any one particular diet.

For many years, vegans and vegetarians from abroad avoided travelling to Japan because it was so hard to find restaurants and shops that would accommodate their needs. Has the situation changed?

There are definitely more options than before. However, they are not available everywhere, and it’s still necessary to do some research in advance. Especially in towns outside of Tokyo, there is still little understanding of vegetarians and vegans. If you’re a non-vegetarian/vegan traveller, you can usually walk around town and find something to eat, but if you’re a vegetarian, it’s much harder. The other thing, and maybe it’s not just a Japanese thing, is that when you go into a convenience store or supermarket and check the label to see if there are any animal products in it, obviously everything is written in kanji. I don’t know how well AI translation software works, but that may be a way to solve the problem, at least in part. Also, now, products marked up as vegetarian or vegan are starting to appear little by little, but if you want to buy a rice ball with umeboshi (pickled Japanese plums), you won’t know if the umeboshi is really vegetarian unless you can read Japanese. Maybe there’s some bonito (small tuna) stock in there. So if you’re a vegetarian or vegan who really cares about the details, it’s going to be difficult. In Japan, when it comes to ingredients, seasonings and manufactured stock, it’s still okay to display vague information. So, some manufacturers and stores have detailed instructions, while others just write “seasonings, etc.”.

While the vegetarian lifestyle is slowly becoming more popular in Japan, there are still some people who are against it. Some people still believe that the vegetarian diet is not very good for your health. What do you think about that?

In the Japanese nutrition world, vegetarian nutrition is not widely supported. When talking about whether a vegetarian diet is healthy or not, it seems that people often pick one single case and use it to prove that veganism is no good. In truth, scientifically speaking, a vegetarian menu is considered good for your health as long as you follow a well-balanced diet. It’s also said that a vegetarian diet cannot provide enough vitamin B12. However, you can easily get it from other reliable sources such as supplements.

For some time, you have been writing reports on the JAS Establishment Project Team for Foods Suitable for Vegetarians and Vegans. Do you think this project, which is organized by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, will have a long-term positive effect on vegetarianism in Japan?

Let’s start with a little background information. According to the international market research company IMARC Group, the global market size for vegetarian and vegan foods in 2020 reached US$17 billion and is expected to grow by 11.4% from 2021 to 2026. On the other hand, there have been cases where companies with no knowledge of vegetarianism have used their own labels on their products, raising the issue of how to choose reliable vegetarian and vegan foods. To avoid this confusion, vegetarian and vegan certification marks have been created, such as the British Vegan Society certification.

Even in Japan, more companies are currently expanding into the vegetarian market, and the government felt the need to regulate the industry and come up with failsafe regulations.

In terms of whether the project you mentioned is a plus or a minus, I think it’s clearly a plus. One of the reasons for this, as I mentioned earlier, is that it’s currently difficult to determine whether something is vegetarian in Japan, so having a label makes it easy to tell at a glance whether this is a vegetarian or vegan product. Such labels were already used by private companies even before the JAS mark was created. I think they were created with good intentions, but as the number of people living a vegetarian/vegan lifestyle has increased, companies have started using their own labels, some of which are far from accurate. That’s why it’s very important to have this reliable vegetarian/vegan JAS mark. On the other hand, the whole process of obtaining the JAS mark then printing and using the new labels may be expensive and time-consuming, so I don’t know how much incentive companies have to join the programme. However, there’s no doubt that it will be a positive thing in the long run, and it seems that the government wants to make the JAS mark fit for use when exporting Japanese products overseas.

Gianni Simone

To learn more on the subject, check out our other articles :

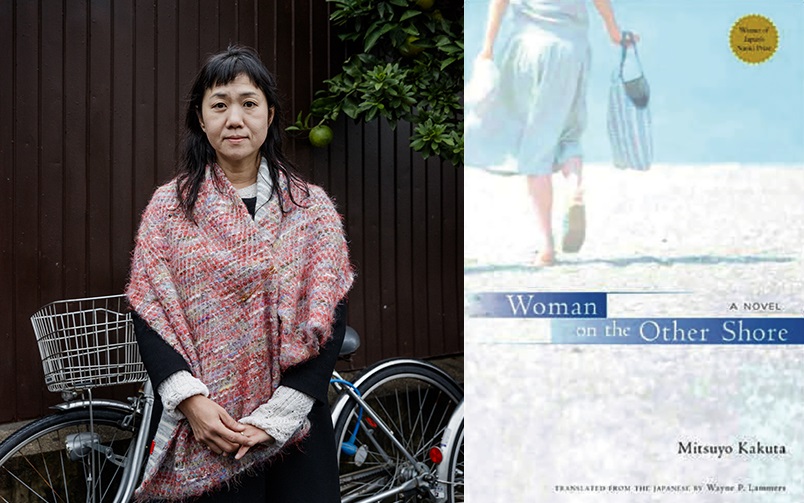

N°135 [TRAVEL] Vegan travel in Japan

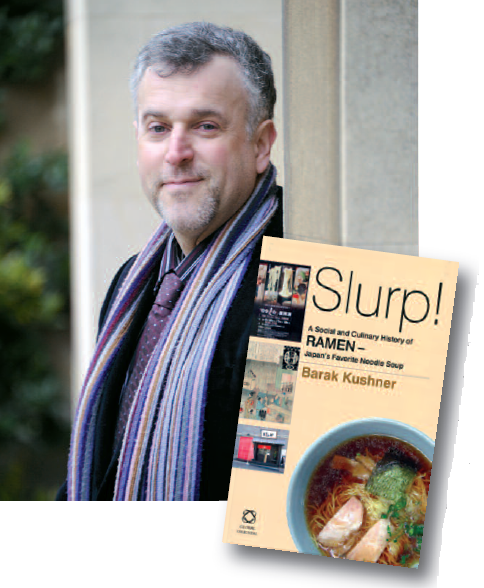

N°135 [CULTURE] Chef Noda Kotaro

Follow us !