It’s in the country’s principal city where the story of the most popular sports began.

It may sound obvious, but most of Japan’s modern sports started in Tokyo. It was in the Japanese capital that some of today’s most popular sports were first introduced from abroad and practised before spreading to the rest of the country. The educators and academic institutions which led the way were mainly located in Chiyoda and Bunkyo wards, and in this article, we’re going to stroll around central Tokyo in search of their stories.

Getting off at Tokyo Metro Kudanshita Station, we enter Kitanomaru Koen so we can admire Nippon Budokan. Though music fans worldwide know it as a famous concert venue, this arena’s primary purpose, as the name suggests, is to host Japanese martial arts. It’s here, in fact, that the national championships of the major martial arts (judo, kendo, karate, aikido, etc.) are held annually. Indeed, the Budokan was originally built for the inaugural judo tournament at the 1964 Olympics, and when the Beatles played here in 1966, many people reacted violently to the idea of such a respected venue being “desecrated” by electric guitar-wielding scruffy foreigners.

Crossing the moat, we reach Kagayaki Plaza, Chiyoda Ward’s facility for the elderly. Hidden between these buildings and overlooked by most passersby, we discover a few stone memorials in an inconspicuous corner along the moat. Among them is a stone commemorating the Japan Athletic Association School of Gymnastics. This is where the current Japan Sports Science University came into being back in 1900. Some people insist that the real site of the school was in present-day Shinjuku Ward, but at that time it was just a sports club. This institute, on the other hand, was funded by the government, which at the time was strongly promoting physical education, and it became a quasi-national university school, though it moved to a different location after only four years.

If you cross the Nihonbashi River on the nearby Kiji Bridge, you’ll find many educational facilities. After the Meiji Renovation, the government used vacant land previously used as a buffer zone against fires to build many schools (even the former Ministry of Education was located in this area). For example, another gymnastics training facility was established in 1878 in the district where Kanda Hitotsubashi Junior High School and the Shogakukan Building are now located. This institute, which later became the Tokyo Higher Normal School and was connected to Tsukuba University’s Physical Education College, was used for training physical education teachers and had a vast athletics field.

In the early 20th century, along with the country’s military expansion in Asia, physical education was considered important for training soldiers. That’s why infantry training was included in the curriculum and some universities even had a shooting range. For many years a heated debate continued between sports advocates and those who thought that men did not need to play games and had to focus on military training instead.

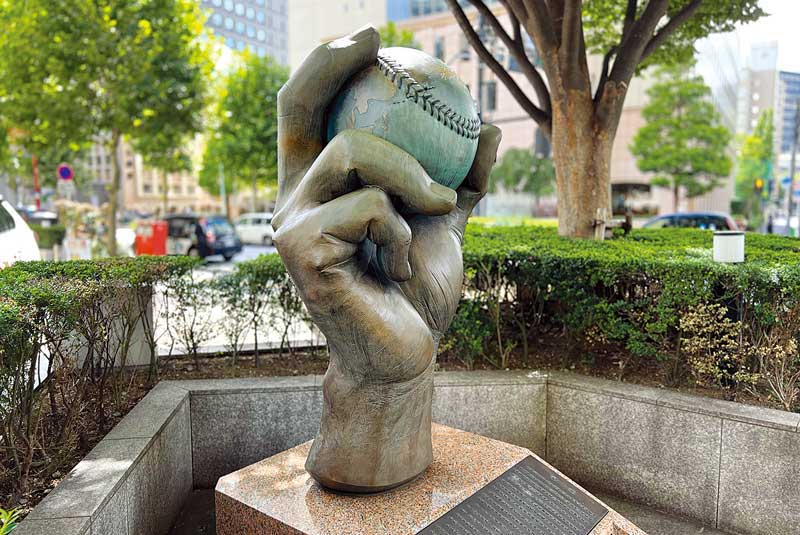

Gakushi Kaikan now stands across the street from Shogakukan, and on the corner we can see a strangely shaped monument on the corner: a giant hand holding a baseball. In 1873, on this site, the precursor to the University of Tokyo was built, and the many foreign teachers who worked there introduced several sports including track and field and rowing. Among them, American instructor Horace Wilson made good use of the school’s splendid playground to play baseball with his students. After a while, baseball grew to the point where fully-fledged games could be played. That’s why this little-known corner of Tokyo is considered the birthplace of baseball in Japan.

The 2.4-metre-high bronze monument was unveiled in 2003, and if you look closely you will notice that a world map is drawn on the ball, and the seam connects Japan and the United States across the Pacific Ocean, symbolizing the internationalization of baseball. It’s also said that the hand holding the ball is a reproduction of the hand of the captain of the University of Tokyo baseball team.

Future haiku master Masaoka Shiki entered this school in 1884 and became so enthusiastic about baseball that he not only kept playing until he fell ill in 1890 but came up with Japanese translations of such words as “batter”, “runner”, “walk”, “flyball”, and “shortstop”, and even wrote poems about the sport. One of them read: “When I saw the ball / and the wood hitting it / and I put on my shirt / I couldn’t believe my eyes.”

Shiki managed to become one of Japan’s foremost poets before his untimely death in 1902 when he was only 34. His contributions to the popularization of baseball through literature include Yamabuki no hitoeda (A Branch of Mountain Rose) which is considered to be Japan’s first baseball novel. In recognition of these achievements, Shiki was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2002.

Even today, the Hitotsubashi, Jimbocho, and Ochanomizu districts are known as student towns as many schools can be found in this area. In time, the massive student presence has attracted shops catering for their hobbies and tastes. Jinbocho, for instance, is particularly famous for its second-hand bookstores and curry restaurants, while Ochanomizu has lots of stores selling musical instruments. The area east of Jinbocho Station, on the other hand, is full of shops selling sports goods. It all started in 1912 when Mitsuno Shoten opened a store that attracted many sports enthusiasts among the students and, after the war, the whole area suddenly became Tokyo’s main sports shopping district. As for Mizuno, it’s still there, the largest sport-related flagship store in the Kanto region.

If we keep walking along this avenue toward Ogawamachi and Kanda stations, we reach the Kanda-Mitoshirocho district. Here, Tokyo YMCA and the Tokyo Christian Youth Hall used to be located. Founded in 1880, they moved to this area in 1894 and played a major role in the introduction of modern sports to Japan, among them basketball and volleyball.

Basketball was invented in America in 1891 and though it was initially banned because it featured a lot of rough contact, it quickly became popular because it could be played indoors in winter when the bad weather restricted other outdoor activities. Then, in 1895, volleyball was invented as a gentler game in which women could participate. Omori Hyozo studied physical education in the United States and when he returned in 1908, taught at the YMCA and brought these two ball games to Japan for the first time together, along with athletics director F. H. Brown.

The YMCA was also known for being the first gymnasium in Japan to have an indoor heated swimming pool. It was there that modern swimming techniques such as the crawl and backstroke were studied instead of traditional swimming techniques. The pool was also used to train Olympic athletes. Starting with Takaishi Katsuo, who won the silver medal in the 800m relay at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, and Furuhashi Hironoshin, who set new world records in the 400, 800, and 1,500m freestyle at the 1949 U.S. National Championships, the Japanese team, which won many gold medals at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics, also held training camps here before the Games.

Omori was the team manager at the Stockholm Olympics, where Japan participated for the first time. Unfortunately, he was unable to continue his promotional activities because he became very ill when the team arrived in Sweden and died in 1913 while returning home from the Olympics. However, the YMCA continued to introduce other sports to Japan such as bowling, boxing, fencing and wrestling.

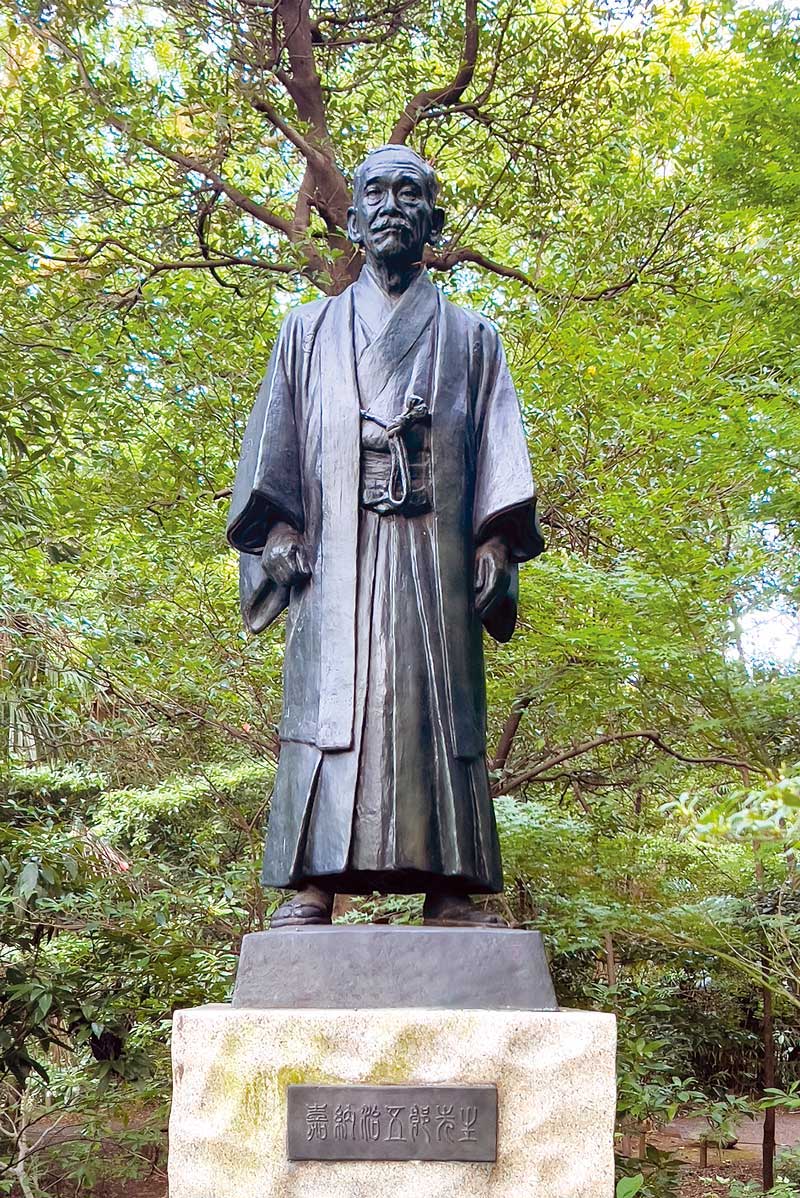

YMCA Headquarters have moved since those pioneering times, and the old site is now occupied by high-rise office buildings, so no need to check out that location. Instead, let’s walk back to Jinbocho Station, hop on the Toei Mita Line and get off at Kasuga. Our next destination, the Kodokan Judo Memorial Museum and Library, is located behind the Bunkyo Ward Office. At the entrance, we are greeted by the statue of Kano Jigoro, one of the main characters in our story.

Kano is universally known as the founder of judo, but he was much more than that. As an educator and school principal, he helped usher modern sport into Japan. Rather than military drills or exercises that simply strengthened the body, Kano aimed for sports that anyone could participate in and enjoy. For him, sport nurtured friendships and lifted your spirits. For more than 20 years, Kano was in charge of the Tokyo Higher Normal School, then became the principal of the Tsukuba University Tokyo Bunkyo Campus

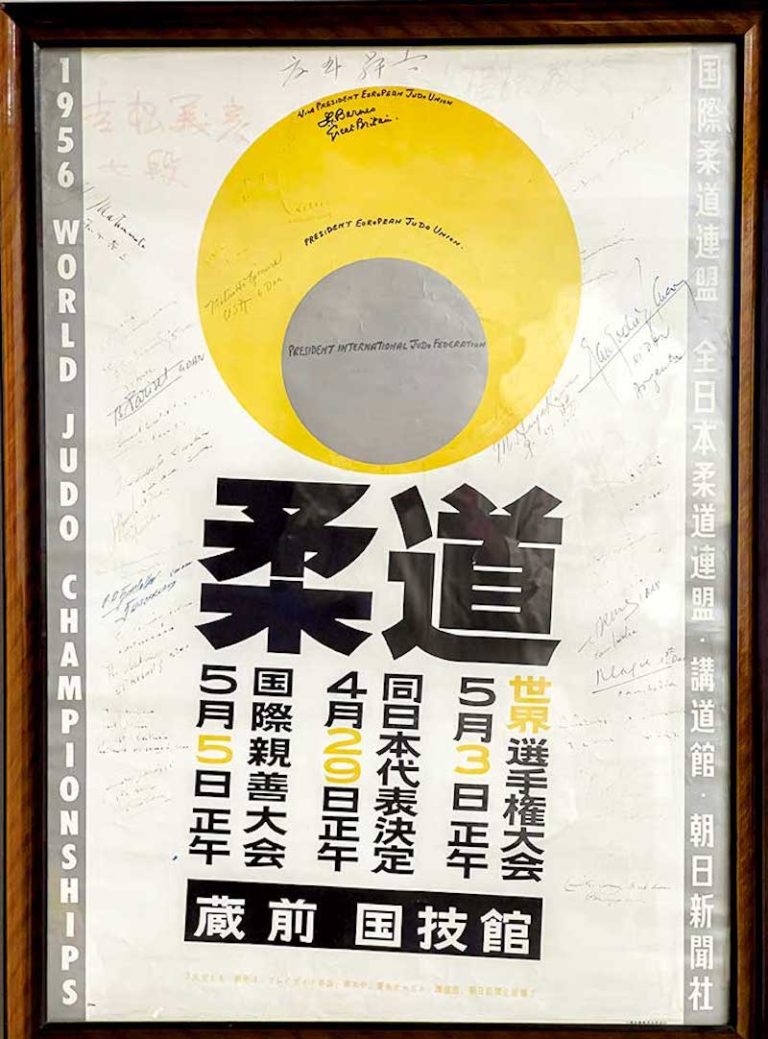

The Kodokan is considered the “temple” of Japanese judo. Originally established in a rented Buddhist temple near Ueno, it later moved to Bunkyo ward. Inside there is a judo museum (you can visit for free during the week) housing important materials related to the development of judo including Japan’s first manual. In addition to books relating to judo, the library also has videos of past matches and tournament programmes.

As mentioned above, Kano’s role went well beyond judo, so be sure not to miss the items relating to Kano’s involvement in other sport events. In 1936, for instance, he attended the general assembly of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) when Tokyo was chosen to host the 1940 Summer Olympics, becoming the first non-Western city to win an Olympic bid. Those Games were eventually cancelled because Japan was increasingly entangled in a costly war with China, but the exhibits in this museum testify to the trust both Japan and the IOC had in Kano.

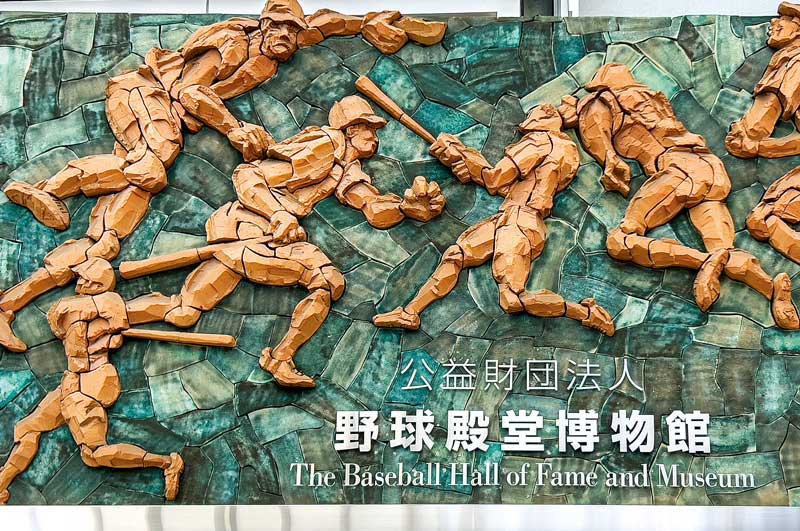

Tokyo Dome City is located just a few minutes walk from the Kodokan, which, besides an amusement park, hot springs, a hotel and many shops, it’s also the home of the massive Tokyo Dome indoor baseball stadium. Though sumo is usually called Japan’s national sport, baseball is undoubtedly the country’s most popular, and it’s on this site that Korakuen was built in 1937 as Japan’s first professional baseball stadium. Throughout the years, the Big Egg, as the Tokyo Dome is nicknamed, has achieved such an iconic status that exceptionally big sites around Japan are commonly measured by stating how many times this stadium can be contained inside them.

Inside the Tokyo Dome is the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Opened in 1959, this is a good place to learn about the origins of this sport in Japan, including important materials from the Meiji period (late 19th century). In addition to portrait reliefs of people who entered the Hall of Fame (including the above-mentioned Horace Wilson and Masaoka Shiki), the museum displays the uniforms of famous players from the past and many other important materials related to the history of baseball in Japan.

Since Tokyo Metro Korakuen Station is nearby, let’s go to the next stop, Myogadani. There are many campuses around here including Takushoku University and Tsukuba University Tokyo Campus. This is also the birthplace of long-distance running in Japan.

Our next character is Kanakuri Shiso, a marathon runner who in 1910 was attending the Tokyo Higher Normal School (now Tsukuba University). At the time, most people in Japan still wore straw and wooden sandals, while runners used a version of tabi (traditional socks) with rubber soles. But Kanakuri wanted something more suitable for long-distance running.

Then, near his campus, he found Harimaya, a tabi store, and asked them for help. Harimaya’s owner accepted Kanakuri’s request and eventually managed to produce a kind of unbreakable tabi that could stand a 40-plus kilometre race. Kanakuri wore them in 1912 when he took part in the marathon at the Stockholm Games, becoming Japan’s first Olympic marathon runner.

The so-called “Kanakuri tabi” proved so popular that they became the Japanese long-distance runners’ footwear of choice until they were replaced by modern running shoes. Even Sohn Kee-chung, a Korean who won the gold medal for Japan at the Berlin Olympics in 1936, wore those tabi.

Harimaya closed down many years ago and today is only remembered by the usual commemorative plaque. However, the area around Myogadani Station is worth exploring. For example, behind the Tsukuba University Tokyo Campus there’s a garden called Senshuen, which in the Edo period used to be part of a feudal lord’s mansion. Today, it’s used for nature observation and is open to the public, and almost in the centre, surrounded by trees and ponds, you’ll find another statue of Kano Jigoro.

It’s said that Kanaguri ran from his dormitory in Ochanomizu to this school every morning. That route is now Kasuga-dori. Along this long wide avenue used to stand the Tokyo Prefectural Women’s Normal School where Kanaguri worked after graduating. Here, he taught tennis to the students and held Japan’s first women’s tennis tournament, paying little attention to those who claimed that women were not made to play sports or exercise, while reassuring the girls’ parents that there was nothing wrong with getting suntanned.

Kanakuri may have run the four kilometres between his dormitory and school every day, but to reach our final destination we prefer to ride the Marunouchi Line again. Close to Otemachi Station, in front of the Yomiuri Shinbun’s main office, is the current start and end point of the Hakone Ekiden, a wildly popular relay marathon that is considered one of the most important events in the Japanese sports calendar.

Having run the monster Tokaido Ekiden (516 km between Kyoto and Tokyo) in 1917, Kanakuri persuaded many universities to take part in a similar annual relay race between Tokyo and Hakone. Kanakuri’s alma mater won the first race in 1920, and the university’s name appears at the top of the list of successive winners in front of the Yomiuri building.

Gianni Simone

To learn more on the subject, check out our other articles :

No.134 [TRAVEL] Tokyo, the cradle of modern sports in Japan

No.134 [ENCOUNTER] Promoting social cohesion

No.134 [FOCUS] Sport is a serious business!

No.134 [TRADITION] Gymnastics for everyone

Follow us !