On 1 September 1923, at 11:58 a.m., a 7.9 magnitude earthquake shook the Kanto region encompassing Tokyo and its surrounding prefectures including Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba. That day a total of 114 tremors were felt. In Tokyo alone, 187 major fires broke out, quickly engulfing the metropolis in flames and burning down homes, industrial facilities and public infrastructure. The death toll has been recently estimated at around 105,000.

When such a huge disaster occurs, the main cause of death varies depending on several factors. For instance, in the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake, which hit the Osaka-Kobe region many people were crushed under collapsed buildings, while in Tohoku in 2011, a many thousands of people were killed by the tsunami that followed the earthquake. In 1923, on the other hand, massive fires were the main cause of death.

Tokyo at the time, and particularly the merchant and working-class districts east of the Imperial Palace and on both sides of the Sumida River, was densely packed with wooden houses, and since the earthquake struck just before noon, many families were using fire to prepare meals. It was reported that 136 fires broke out throughout the shitamachi area of Tokyo and quickly spread across a wide area due to winds blowing into the Kanto region from a typhoon moving north along the Sea of Japan coast at the time.

This city-sized firestorm in turn produced a gigantic fire whirl, which on 3 September killed 38,000 people who had taken refuge at the Army clothing depot in Honjo Ward (the site of today’s Earthquake Memorial in Yokoamicho Park). It was reported that many victims were swept up by the fire whirl, and some of the victims of the clothing depot were blown as far as Ichikawa, about 15 km away.

In the end, 90% of all casualties were due to fires (91,781 out of a total of 105,385 victims). Also, it has been estimated that 1.9 million people were affected, about 109,000 buildings were completely destroyed and some 212,000 burned down.

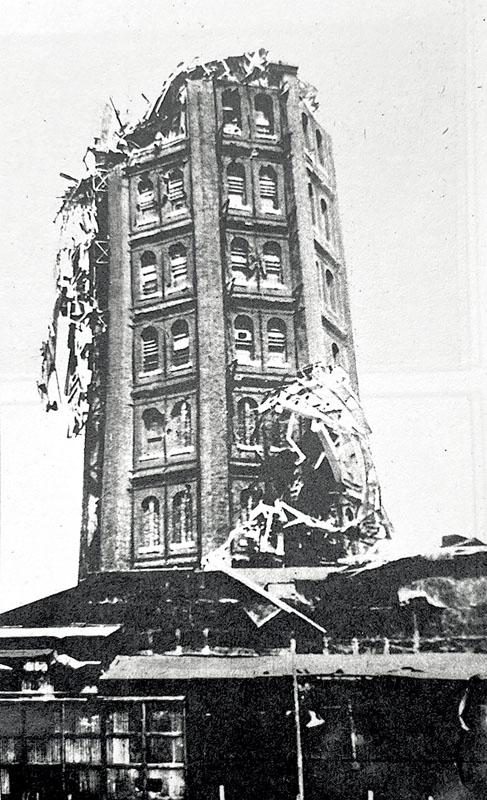

Among the damaged buildings were those housing government offices such as the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Metropolitan Police Department. Other places were destroyed by fire, including educational, cultural and commercial facilities such as the Tokyo Imperial University, the Imperial Theatre and the Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi Main Store. However, the most prestigious casualty was the Ryounkaku (literally Cloud-Surpassing Tower), a 68.58-metre tall Western-style skyscraper, which at the time was Tokyo’s most popular attraction. The Asakusa Junikai (Asakusa Twelve-Storeys), as it was affectionately called, had been built in 1890 in the Asakusa district and housed Japan’s first electric elevator as well as 46 shops selling the latest technological wonders from around the world. The earthquake destroyed the upper floors and damaged the whole tower so severely that it had to be demolished with explosives on 23 September.

As about 60% of the houses in Tokyo were damaged, many residents moved to nearby evacuation centres. According to a survey conducted immediately after the earthquake by the city of Tokyo, by 5 September there were 160 mass evacuation sites with more than 12,000 evacuees. Shrines and temples, a total of 59, were the most numerous, followed by schools with 42. The Earthquake Relief Secretariat of the Ministry of Home Affairs borrowed tents from the army, while from 4 September, the ministry’s Earthquake Relief Secretariat and the Tokyo Prefectural Government began the construction of barracks for temporary-housing.

Charles Schencking, a historian of modern Japan at the University of Hong Kong, has researched the disaster and its wider implications. In The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan (2013), he identifies two main narratives that were amplified by the earthquake. The first narrative saw the disaster as “divine punishment” for the country’s indulgence in luxuries and its over-consumption; the second saw the event as an opportunity to rebuild Tokyo as a modern, world-class city.

Indeed, this was also the opinion of American political scientist and historian Charles A. Beard in 1923. Beard had visited Japan just months before the earthquake to research his new book, The Administration and Politics of Tokyo. He travelled again to Tokyo soon after the disaster at the invitation of the newly appointed Home Minister, Goto Shinpei, and after surveying the damage, he changed the forward to his book to read: “The earthquake and fire destroyed many of the physical features of Tokyo described in the following pages. The disaster has wiped out as well many of the physical obstacles which have stood in the way of the realization of the plans for city betterment. It is destined also to clear the field of old prejudices and entrenched practices and to make room for a new city government properly organized for its new tasks.”

It is no coincidence that Beard was invited by Goto because it was the former mayor of Tokyo who led the restoration project and would be known later as the “father of urban planning”. He first tried to establish a Ministry of Reconstruction of the Imperial Capital to centralize the authority of local governments and take over their affairs under the jurisdiction of each ministry, but met with strong opposition from the other ministries, and in the end, established instead the Imperial Capital Reconstruction Institute, an administrative body that was directly involved in drafting the reconstruction plan.

Even before the earthquake, when he was Mayor of Tokyo between 17 December 1920 and 20 April 1923, Goto had come up with a plan to revolutionize the city. At the time, however, Tokyo City’s annual budget was about 130 million yen, while the necessary expenses envisioned by Goto’s plan required 800 million, so in the end, the project was scrapped.

After the disaster, Goto declared that not only would the capital not be relocated, but that the post-earthquake reconstruction offered a great opportunity to build an ideal imperial capital in Tokyo. He aimed for a fundamental urban remodelling rather than a simple restoration; a new city that put the safety of citizens first, would not suffer major damage in the future and would be organized along more rigorous and rational principles (e.g. relocating the big fish market from Nihonbashi to a more convenient spot in Tsukiji).

His ambitious plan originally called for 1.5 billion yen, equivalent to about one year’s national budget at the time. However, it was strongly opposed by both the business world and the largest opposition party, the Seiyukai, which was at odds with Goto over the introduction of universal male suffrage. They demanded drastic cuts, and a special committee eventually agreed on 468.44 million yen.

Goto’s ideas were progressively rejected by the government and he was finally ousted from the Cabinet on 7 January 1924. Even the Reconstruction Institute was abolished, and on 25 February 1924, the Reconstruction Bureau was established. It quickly fell into disrepute to the point of being referred to as the “Public Hall of Demons” as many of its members were arrested and prosecuted for taking bribes.

However, those setbacks did not put an end to the reconstruction plan. For example, one of the achievements of the project that can still be found in Tokyo today is the new road network. In tackling this problem, Goto referred to the remodelling of Paris carried out by Georges Haussmann, who was the governor of the Seine prefecture in the middle of the 19th century. He was adamant about the necessity of both roads radiating out from the city centre and the importance of a ring road, and although the plan had to be scaled back, a lot was done to improve the situation. Typical examples that have survived to this day are Showa-dori, the city’s north-south axis, and Taisho-dori (today known as Yasukuni-dori), which cuts through Tokyo longitudinally. Also, Meiji-dori was created as the basis for a loop line. In total, 22 arterial roads were built, while the paving of roadways and the separation of sidewalks and roadways progressed throughout the city.

The original proposal was a large-scale concept, with the width of the main streets ranging from 70 to 90 metres, including wide sidewalks, and green belts of land in the centre or separating roadways and pavements. However, Goto had not taken into account Japan’s strong sense of absolute ownership of land and other restrictions on property rights. As a result, he faced fierce resistance from landowners.

Today, the best surviving example of what Goto had in mind is Gyoko-dori. This 190-metre-long, 73-metre-wide street connects Tokyo Station’s Marunouchi Central Exit with Uchibori-dori in front of the Imperial Palace. It is usually closed to traffic and is only used as a road for imperial ceremonies and for foreign ambassadors on their way from Tokyo Station to the Imperial Palace for ceremonies to present their credentials.

In a city like Tokyo, which at that time had many more rivers and canals than now, bridges were as important as roads to revive Tokyo’s transportation and communication network. Unfortunately, most of the city’s bridges were severely damaged by the earthquake, which made it necessary to systematically build new and stronger structures that could withstand a future major disaster. At the time of the quake, five iron bridges had already been built over the Sumida River using wood for their bases and bridge boards. For this reason, three of them, including Eitai Bridge, caught fire, and many of the evacuees burned to death or drowned.

When the time came to rebuild the nine bridges over the Sumida River, both aesthetics and strength were emphasized in their design. Goto set up a design investigation committee consisting of artists, architects, landscapers, etc. Foreign case studies were taken into consideration, and the opinions of painters and writers were sought to create a design suitable for the restored imperial capital.

As the first bridge that is encountered going up the river, Eitai Bridge was seen as the gate to the imperial capital and deserved special care. It was modelled on the Ludendorff Railway Bridge that spanned the River Rhine in Germany. Today, it is the oldest existing tied arch bridge and the first bridge in Japan with a span length exceeding 100 metres.

Another eye-catching structure is the Kiyosu Bridge, which at the time was touted as the “flower of earthquake reconstruction projects” and was modelled on the suspension bridge in Cologne over the River Rhine. Even writer Nagai Kafu was so impressed by the view of the Sumida River from Kiyosu Bridge that he included it in his essay “A Walk in Fukagawa”.

In this way, the bridges over the Sumida River added a high degree of symbolism to the Tokyo urban landscape while each bridge asserted its own diverse character. All in all, the Reconstruction Bureau is said to have built more than 100 bridges.

The devastation caused by the fires burning down so many houses prompted the authorities to create an ad hoc organization to both support the reconstruction and improve the housing conditions for at least a part of the population. This led to the creation of the so-called Dojunkai Apartments: reinforced concrete housing complexes equipped with what at the time were state-of-the-art modern facilities such as electricity, city gas, water supply, rubbish chutes and flush toilets. Between 1924 and 1933, the Dojunkai Foundation built 13 residential blocks in Tokyo (with a total of 2,225 apartments) and two in Yokohama (276 apartments). The tenants were recruited from the general public. Residents were mainly urban middle-class office workers.

One complex in particular, the Otsuka Women’s Apartment, was reserved for single professional women and was equipped with a lift, a dining room, a communal bath, a lounge, a shop, a laundry room, and a music room and solarium on the roof. Singer and actress Togawa Masako lived there with her mother between 1923 and 1962. When she became a mystery writer, in 1962, she set her debut novel, The Grand Illusion (French title: Le Passe-Partout; English title: The Master Key) in that very apartment and went on to win the 8th Edogawa Ranpo Award.

Unfortunately, none of the 15 complexes has survived. Having become old and beginning to erode, their once-advanced facilities hopelessly outdated compared to the apartment blocks built after the Pacific War, they were torn down one after the other between 1984 and 2013 despite opposition from several conservation groups. Only a fragment of the Aoyama Apartments in central Tokyo can be seen today. When the Bauhaus-inspired building was replaced by the Ando Tadao-designed Omotesando Hills shopping complex in 2003, a copy of a small section of the old apartments was built at the eastern end of the new building by using materials such as those used in the past.

Speaking of buildings, the government undertook the construction of reinforced concrete elementary schools with international support including donations from the United States. The design of the school buildings was influenced by German expressionism, which was considered to be cutting edge in that era. Sano Toshiki, a professor at the Tokyo Imperial University, was asked by Nagata Hidejiro, the mayor of Tokyo, to serve as the director of the Construction Bureau of the City of Tokyo. Under Sano’s initiative, design concepts based on rationalism were introduced, and modern facilities such as flushing toilets, heating equipment, and classrooms that emphasized science and civics education were added, pursuing the idea that hygiene should take root in the population from an early age.

Together with the process of land readjustment, parks were developed in various places as green spaces were deemed necessary not only to beautify the capital but also as future evacuation centres. The original plan aimed at creating parks of a size comparable to those in Paris, London and New York, but even in this case, they had to settle for much smaller spaces. Three of those them – Sumida Park, Hamacho Park and Kinshi Park – can still be visited today. Sumida Park is located on both banks of the Sumida River and at the time it was Tokyo’s first riverside park. In particular, it’s famous for the cherry blossom trees stretching along the river for around a kilometre. They were originally planted by the 8th shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune.

In the end, lack of money, opposition from local interests, and other logistical problems placed limits on what could be realistically accomplished, and the scope of the project had to be significantly reduced. Also, only 20 years or so after the earthquake, Tokyo was hit by another huge tragedy when US military bombing – especially the Great Tokyo Air Raid on 10 March 1945 – again reduced vast parts of the city to a burnt wasteland and caused more than 120,000 casualties. Even so, Tokyo’s current urban system, its parks and public facilities, were developed at that time and owe a great deal to the 1923 reconstruction plan. In this respect, the ideal city that Goto Shinpei partially managed to build forms the framework of contemporary Tokyo.

Gianni Simone

To learn more on the subject, check out our other articles :

No.133 [HISTORY] The dark side of the earthquake

No.133 [TRAVEL] Waiting for the Big One

No.133 [INTERVIEW] Imaging disaster: Gennifer Weisenfeld

Follow us !