The prefecture’s second daily newspaper argues with passion and professionalism for a return to normality.

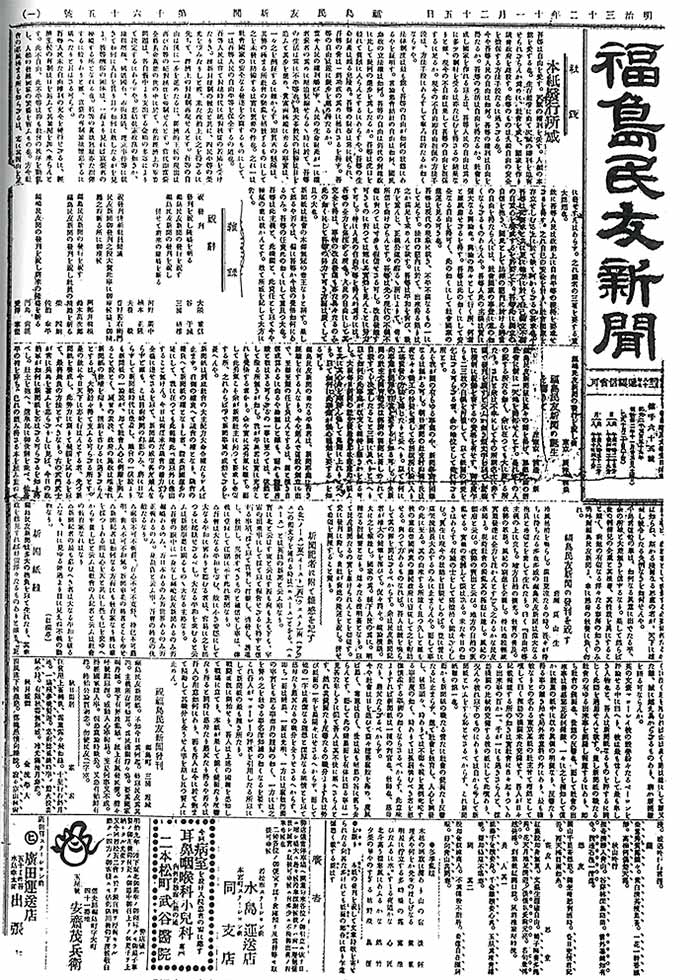

The Fukushima Min’yu is one of Fukushima’s two main newspapers. Founded in 1895, it was suspended for about four years during WWII when media restrictions were imposed and each prefecture could only have one newspaper. However, it resumed publications in 1946. “I think we have a reputation for being rebellious,” says editor-in-chief Ono Hiroshi. “I am not saying that the Fukushima Minpo [Fukushima’s other daily] is not free and open-minded, but I guess we have a stronger reputation for it than they do. We are a company that dislikes being restricted, and this attitude is reflected in the atmosphere of the paper and our corporate culture.”

Since 1948, the Fukushima Min’yu has collaborated with the Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s largest daily. Originally, the partnership sought to help the Min’yu stabilise its management during the post-war period. In 2009, the two companies came to an agreement on editorial cooperation. In particular, once a month, a Min’yu article on the progress of recovery is published in the Yomiuri Shimbun’s English edition, The Japan News, while a factory in Koriyama belonging to the Yomiuri Shimbun Group prints both the Yomiuri Shimbun and the Fukushima Min’yu.

“We are not a big company,” Ono says, “and we welcome this kind of collaboration. We currently have about 100 reporters, including some who do other jobs as well. On average, we hire five or six new reporters every year, mainly from the Kanto region [Tokyo and surrounding prefectures], though we get applications from all over Japan. We hire a little in excess of our needs because, lately, a growing number of young people tend to quit their job pretty quickly (laughs).”

Ono points out that the female presence on the paper has been steadily increasing. “I think there are about 30 to 40 female reporters right now,” he says. “Traditionally, the newspaper industry is a male-dominated one, but among university students, more young women seem to be interested in doing this job. On the other hand, a lot of young men prefer to start their own business or work in IT.”

According to Ono, this new trend is the result of changes that occurred at the end of the last century. “Reporters are expected to be available 24/7. They may have to work into the small hours to pursue a story or interview someone. There was a time when female journalists were expected to work like men, but at the same time, it was hard to send a woman to certain places that were deemed dangerous or assign them to meet someone in a bar late at night. For those and other reasons, for a long time, women were unable to make inroads into the news world.

“However, things have gradually changed, starting in the 1980s and 90s. This has happened everywhere, in every sector, as women’s presence in the job market increased and we began to value their contribution. In our company we have created the conditions for women to do this job in a safer environment, keeping in mind their needs. For example, we have devised ways to make it possible for women to continue working as journalists while raising children. How can a woman maintain her skills as a journalist in such conditions, and what kind of work can she do? For example, we want to make it possible for reporters on the scene to be replaced by a colleague at short notice, like if her child suddenly develops a fever. I think they also want a child-care room at our company so that reporters can use it while working.

“Another issue that was raised after 3.11 was the risks connected to radioactivity. To begin with, the first reporters who were sent to the nuclear plant were relatively older men. Then, when we needed more people on the scene, we sent younger men and women. As you can imagine, it is a dangerous place and definitely not the kind of environment where everybody wants to go. Also, reporters’ families could object even if the journalists themselves wanted to go. Yet, some female reporters wanted to see the disaster area for themselves. It took about four years but, eventually, even women were able to visit the nuclear plant and other no-go areas.”

Asked about the paper’s readership, Ono says that the Min’yu is read by a wide range of people. “However, it is true that we have many middle-aged and elderly readers,” he adds. “We are exploring themes such as gender issues to attract more women. We should provide more information useful to women in their daily lives and offer advice on how they can play a more active role in their community and society at large. Another good idea would be to publish comics from a woman’s point of view.”

Ono points out that a female member of the Diet, who comes from Fukushima, is currently serving as an aide to Prime Minister Kishida and is dealing with gender issues. “Last autumn, there was also an event in which we discussed the best way women can contribute to society,” he says, “and in February, we held a similar event at Hawaiians in Iwaki to encourage the active participation of women in the Yomiuri Shimbun.”

Hawaiians is a popular spa resort in the south of Fukushima Prefecture and its choice for such an event is probably not a coincidence. For most of the 20th century, this area was famous for its coal mine but, in the 1960s, oil replaced coal as the industry’s main source of energy and the company had to lay off many miners. In order to create alternative jobs for its employees and their families and to secure a new source of income for the company, the launch of a new venture other than coal minig was decided. Since the area is full of hot springs, a spa resort with a Hawaiian theme was opened in 1966, and quickly became one of the most popular attractions in the country. One of the resort’s most well-known features was its hula dance troupe, which was originally comprised the daughters of the miners. They were even the subject of a feature film called “Hula Girls”, and after Hawaiians was damaged by the triple disaster, the troupe toured the country to cheer up the many people who had been forced to leave their homes.

Fukushima is a very large prefecture and its size poses many problems to companies that are struggling to reach as many readers as possible. “The news world may be online,” Ono says, “but millions of Japanese – particularly older people – still prefer newspapers. Each company has an extensive distribution system through which they deliver their papers every morning to their subscribers. However, winter in Fukushima can be very harsh, especially in western districts like Aizu Wakamatsu. Delivering newspapers to areas where it snows a lot is a daunting task. People are gradually returning to the disaster areas that were evacuated in 2011, but still not in large numbers. They are sometimes scattered in isolated areas, and there are still few delivery people so it remains difficult to reach subscribers’ addresses.

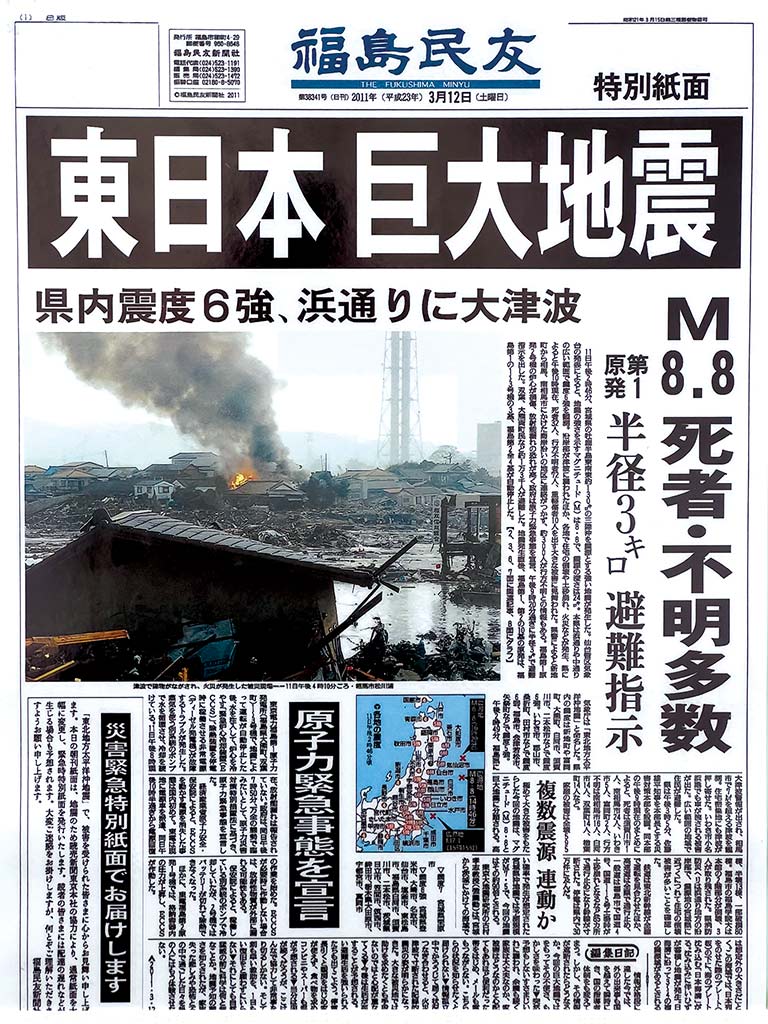

The Min’yu’s efforts to keep a widespread and efficient distribution network are all the more important because, like most traditional media, they have been losing readers. “Until the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, we had a circulation of 180,000,” Ono says. “But many of those readers lived in the Hamadori region [Fukushima’s coastal district], which was the worst hit by both the tsunami and nuclear accident. Many died and many survivors were evacuated and stopped subscribing. As a consequence, our circulation fell to about 156,000. Luckily, many readers have kept supporting our paper, and we were able to withstand the crisis.” Even the Fukushima Min’yu did not escape tragedy as, on 11 March, one of its reporters disappeared in Minami Soma after being swallowed up by the tsunami. “We teach our reporters about safety but, in the end, it is up to each person to judge the situation while on the job. When it comes to how far we should cover the story and how far we should stand on the front line, it is up to each of us to make our own decisions.”

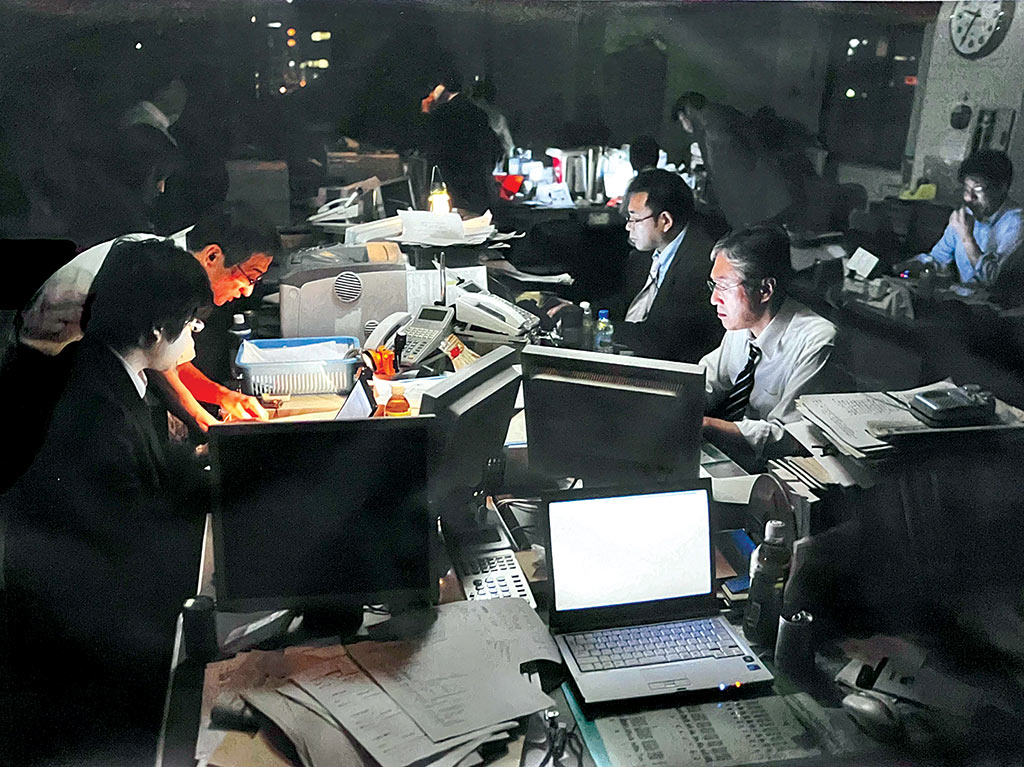

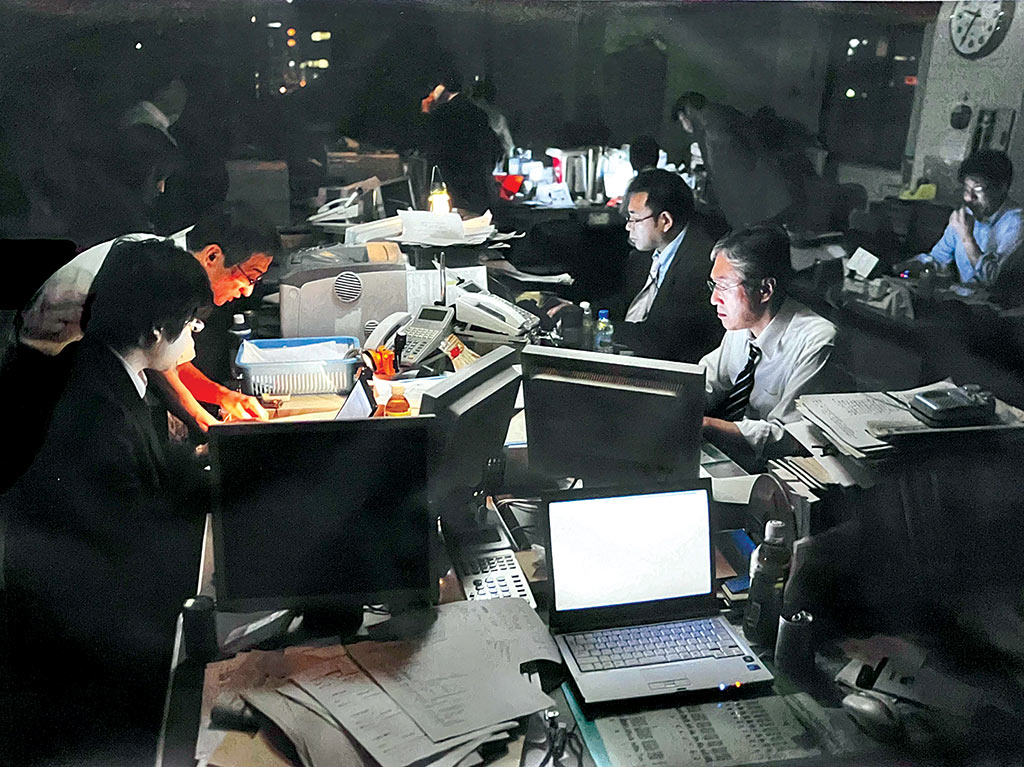

In many ways, the events of March 2011 have brought about a revolutionary change both in the prefecture and local journalism. “Many readers suddenly disappeared,” Ono says, “and recovering from that damage has been a 12-year battle. But we have learned many things along the way. First of all, we have learned how to deal with disasters in the future, both natural and man-made. As for us journalists, 3.11 has confirmed that we should provide information that is really necessary and useful, by any means possible. In the immediate aftermath of the disasters, for example, delivery trucks stopped travelling to Fukushima and there was a severe shortage in the supply of daily necessities. At the time, we often reported on how and where people could obtain things. Later, with many people’s lives being affected by the nuclear plant accident and the debate raging around nuclear energy and radiation, we created regular columns to keep our readers informed on the subject, asking doctors and scientists to write important information in an easy-to-understand way. Thus, we started collaborating with a young doctor, Tsubokura Masaji who, in 2011, had moved from Tokyo to Minami Soma to support the Hamadori disaster area. He began to study how radiation affects the body by conducting internal examinations using a whole-body counter and informing the residents of his findings. Tsubokura is now a professor at the Fukushima Medical University and, for many years, he has written a column to explain radiation-related issues in a way that even ordinary readers can understand. I think he has written some 490 columns so far.”

Ono thinks that 3.11 has contributed to changing the media’s mission to convey information and support their readership. “A lot of people were evacuated after the nuclear accident and went through a very difficult time,” he says. “They may have been able to receive compensation from TEPCO, but their lives were disrupted by having to move far away where their presence was not welcome. We adopted the stance that they did not have to blame themselves because, after all, they were victims of the disaster. We also tried to put across the message that, though it was difficult, we have to strive to be independent and not just live on government hand-outs or charity.

“In the midst of all this, another issue emerged concerning the release of the nuclear plant’s treated water into the ocean. The reason why a lot of people are against it is that they are understandably afraid, but I think that limiting our response to an emotional reaction does not help solve the problem, and we cannot move to the next step unless we deal with it scientifically. In particular, we have to consider that there will be no hope for the future of the disaster area until we dispose of the waste and move on. The discharge will probably start in some months, but most media including the major newspapers keep saying that this cannot be done because the fishermen are going to suffer. What we are saying is that our studies show we can release tritium into the environment without too great a risk as long as this process is scientifically controlled.”

Ono is also critical of the way the media outside Fukushima have reported on the prefecture since 3.11. “A little more than two or three years after the accident at the nuclear power plant, people started to come back,” he says. “More and more people returned to their homes, yet most outsiders who visited Fukushima only collected shocking photos and the opinions of people who were going through hard times.

Basically, many people’s image of Fukushima has not changed in the last 12 years. Its image is of a place that should not be visited. Today, this is still the case as even now there are overseas photojournalists who only focus on the broken and neglected areas. In other cases, areas that were never affected by the disasters are treated as dangerous. I have made several appeals pointing out that everybody should see Fukushima as it is now. Many people are definitely doing their best to change the situation, particularly young people who are taking on new challenges and, I believe, are creating the new Fukushima. I would like more people in the media to come and see this new development. There are a lot of really interesting people they can meet and talk to.

Even the disaster area is changing dramatically.” Governor Uchibori has been at the centre of Fukushima’s reconstruction drive and Ono is generally satisfied with what he has done. “We have known each other prior to him becoming governor,” he says. “He is a very capable man who makes sound policy choices, particularly in terms of his relationship with central government, and avoids big mistakes. Unlike past governors, he does not fight the people in Tokyo. He knows very well when to push, where to push hard, and when to pull. This is his major quality, but also his major fault. There are times when I wish he had done more, but he is sometimes too cautious about what he wants to say. He is a person who does not like to take risks or make mistakes. That, I think, is one point where there is still room for improvement. However, he has been at the helm for eight years and has just been re-elected, so I feel he may do things a little differently this time. I look forward to seeing how it goes.”

While Fukushima is struggling to change its image, the Min’yu is getting ready to meet the new challenges posed by the digital age. “Overall, the new generations, and especially Generation Z, no longer read newspapers and are becoming less familiar with the traditional transmission of news and culture,” he says. “There are more and more people who never buy newspapers, and this is not only a problem for our company but a big headache for the entire media world. It appears clear that in the not-too-distant future it will be difficult to continue producing newspapers that do not have another source of income other than the traditional paper editions. Each company is currently taking on the challenge of creating an alternative business model, and we are trying to do the same. Admittedly, our technological capabilities are not comparable to those of the major dailies like the Asahi or the Nikkei. We are taking small steps in that direction but for us, the web is still something extra that we have not yet found a way to make profitable. I admit that we are very cautious about deciding whether or not to add a paywall and start digital subscriptions.

“Getting young people interested in reading our newspaper is a big challenge because their relationship with the news and the media has completely changed from what it used to be when I was their age. So I have been actively asking our young journalists to come up with ideas, and I am trying to figure out how to assimilate those ideas and turn them into a workable system. In that regard, last year we changed the way we post on social media to appeal to young people. We are dealing with this issue step by step.”

As if these structural changes were not enough, in the last three years the news world has had to deal with Covid-19, which has caused a new set of problems. “Obviously, we were greatly affected by the pandemic,” Ono says. “From an editorial point of view, the biggest issue has been how to secure enough people to do the job at any one time, so I have been careful to let infected people remain at home as much as possible. Another problem was that a lot of shops, restaurants and bars had to close and, for a long time, we could not organise any events. Advertising revenues inevitably dropped while the whole economy fell to pieces. It was, in other words, a vicious circle, which was almost impossible to escape.

“Unfortunately, the pandemic ended up sabotaging our plans for the Olympics as well. In Fukushima, the Games were seen as a way to showcase our prefecture and I had high hopes that we had been able to hold discussions with that in mind. We wanted everyone to know that Fukushima was changing in many positive ways, but the event was delayed by a year and, in the end, it did not have much of an effect. I hope that we are now on the road to recovery, and we are looking for opportunities to present our prefecture to overseas travellers as well as whoever remains convinced that Fukushima is still uninhabitable.” Ono has been editor-in-chief for the past five years and is looking forward to better days for both his paper and the prefecture. “As I mentioned earlier, one of the characteristics of newspaper companies is that they must try to face each issue with clear ideas and the right attitude,” he says. “For example, we cannot deal with problems related to the nuclear accident unless we look firmly into the future and take a scientific approach to those problems.

“I do not know how long it will take to achieve a complete recovery, whether it will take 50 years or a lifetime, but we have to keep communicating the values in which we believe. That is why we are nurturing reporters who can continue our mission and work on new projects. We will remain committed our editorial line until a new Fukushima is born.”

Gianni Simone